Angels and Demons

Daniel Muzyczuk

Daniel Muzyczuk is the director of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. Curator of exhibitions including Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957–1984 (with David Crowley), Notes from the Underground: Art and Alternative Music in Eastern Europe 1968-1994 (with David Crowley), The Museum of Rhythm (with Natasha Ginwala) Through The Soundproof Curtain: The Polish Radio Experimental Studio (with Michał Mendyk), Work, work, work (work). Céline Condorelli and Wendelien van Oldenborgh (with Joanna Sokołowska), among others. Co-curator of the Polish Pavilion of the 55th Venice Biennale (with Agnieszka Pindera). His upcoming book is entitled Twilight of the Magicians (2025, Spector Books).

Research Title Angels and Demons

Category Essay

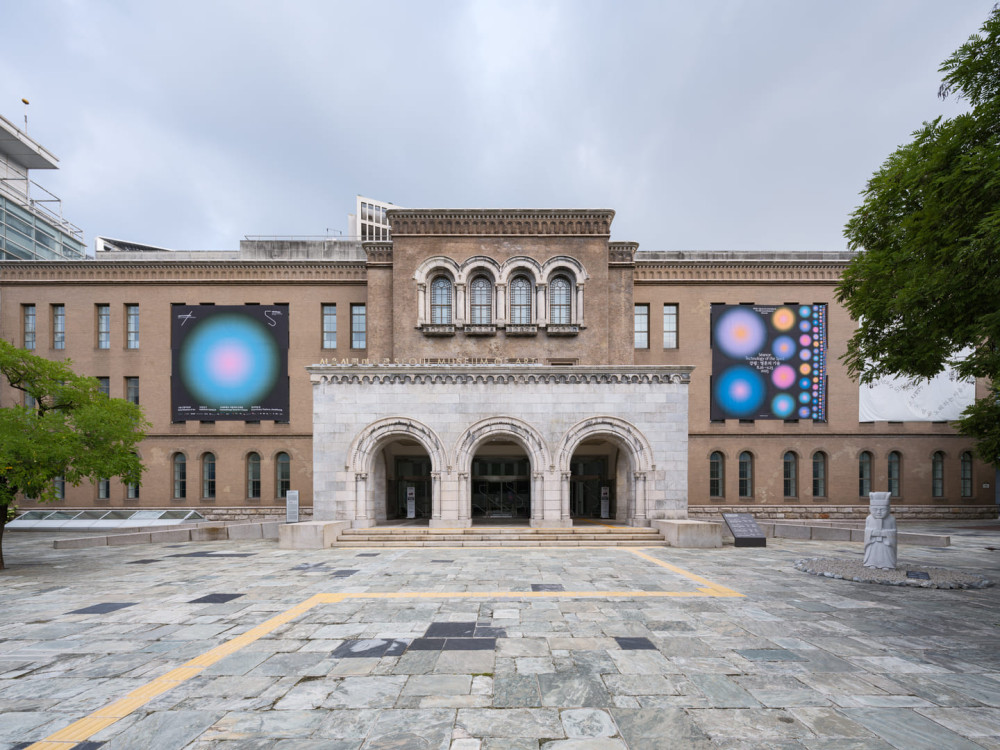

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Daniel Muzyczuk

A family is riding in a car. Collectively they experience a sudden change in the ambience. This shift jolts the driver, who was on the verge of fainting, back into consciousness. A terrible accident is averted. The nature of the phenomenon is hard to ascertain. And yet, everyone felt something.

The writer Meredith Young-Sowers was one of those in the car. She later ascribed the grace that came upon the passengers to a reconfiguration of their “personal resonances.” A shift in one of the “tones”—that which she associated with the driver—was altered by nearly passing out. This upset the serene harmony of the other tones in the car, alerting everyone to the danger.

Young-Sowers saw this as confirmation of the theory passed down to her by a mysterious “Mentor,” an angelic entity that showed her the path to enlightenment. She wrote a book of teachings and published a series of meditation tapes for personal spiritual advancement.1 Seven compositions were dedicated to seven chakras located in different parts of the body: spiritual quests, intuition, communication, love, personal power, connection with the earth, and emotional and sexual balance. All of them are based on analogue drones arranged into harmonic triads and are stylistically very close to the classics of minimalist electronic music. Yet these pieces have clearly defined practical uses. The different combinations of triadic tones affect certain chakras and help stimulate their activity, attuning the listener’s inner pitches so that they start resonating at the desired frequency.

This is all based on a very old theory about the nature of reality. Pythagoras, one of the founders of mathematics and the inventor of tone theory, was also the spiritual leader of a religious sect. Its members believed that harmony was the governing principle of the universe, as expressed in the “music of the spheres,” and that every part of life could be beautiful and right if aligned with this basic law. Harmonious intervals in music derive from the relations between stars in constellations, which also dictate the coordination between body and soul. Thus “music is the expression of the will of nature,” as Rudolf Steiner wrote, “while all the other arts are expressions of the idea of nature. Since music flows nearer the heart of the world and is a direct expression of its surging and swelling, it also directly affects the human soul.”2

The event narrated by Young-Sower has two aspects. In one sense the phenomenon is spatial: the combination of tones (and their disruption) is particular to the setting. The sound has a spatial arrangement, which is established by the listener’s place within that harmonious configuration. Yet in another sense it is outside of space: the relationship between the various personal tones is telepathic. They are not so much heard as “felt,” in a way that is not localized.

Sound telepathy is a phenomenon that recurs at unexpected junctures in the history of music. A famous—and probably apocryphal—anecdote connects it to Anton Webern and his use of the compositional marking “pensato”: a sound so quiet that it can only be thought by the performer. This note should not be manifested as a wave perceptible by hearing, but as a mental vibration that could be transmitted from one mind to another.

Webern, of course, rose to fame as the most compelling representative of the twelve-tone method that challenged the harmonic system established by Pythagoras. The latter gave equal prominence to all tones in the scale, but composers working within this new system established a different set of rules. Webern worked with a very strict compositional structure based on mathematical logic. Consequently, he continues to be regarded as an extreme rationalist, when in fact he was deeply enmeshed in new forms of spirituality rooted in esoteric theosophy. His work was deeply affected by the death of his mother, and he understood his music as a tool for spiritual advancement towards a new reality. In a 1910 letter to Shoenberg, he explained the true meaning of the twelve-tone method and the liberation of tones: “If there is a development, then it can only be this: Out of the animal-man a living being gradually grows that comes to realize that it does not need life on this earth. Thus the human being disappears again, the physical one.”3

In lectures Webern gave later in 1932–33, he said:

n the harmony [that Schoenberg] developed, the relationship to a key note became unnecessary, and this meant the end of something that had been the basis of musical thinking from the days of Bach to our time: major and minor disappeared. Schoenberg expresses this in an analogy: double gender [Zweigeschlechtigkeit] has given rise to a higher race [Übergeschlecht]!4

Music does have a role to play in humanity’s development: not towards a “higher race” of “man” but rather so that we might transcend such things as race, species, and gender entirely. As the art form closest to nature, Rudolf Steiner thought of music as a laboratory for the reconciliation of opposite forces, bringing balance to the universe: the marriage of heaven and hell. So it might be argued that, rather than overthrowing it, Webern was in fact returning to the first principles of the theory of harmony: as the traditional method of organizing consonances reflected a model based on the eternal order of divine bodies, so founding a new set of arrangements would inaugurate a new world.

Webern was obsessed with the genderless angels that he saw in the poetry of Reiner Maria Rilke and especially in Honoré de Balzac’s novel Séraphîta (1834). Inspired by Emanuel Swedenborg, the novel focuses on a man and a woman in love with the titular hero/ine, a perfect androgyne who appears to the first as a woman and to the second as a man. Balzac ends with a vision of their assumption into heaven which features several musical metaphors that might serve as a key to unlocking Webern’s tightly organized form:

Each world possessed a center to which converged all points of its circumference. These worlds were themselves the points which moved toward the center of their system. Each system had its center in great celestial regions which communicated with the flaming and quenchless motor of all that is. Thus, from the greatest to the smallest of the worlds, and from the smallest of the worlds to the smallest portion of the beings who compose it, all was individual, and all was, nevertheless, One and indivisible.5

Balzac shows us constellations of worlds, each operating in accordance with their own parameters. This strategy was used by Webern to form his compositions. They are finely constructed mechanisms that model new worlds with unearthly rules. Their brevity and compression also suggest a way out of the terror of temporality; ideal for the age of recordings, they only reveal their intricate structures on repeated listening. The experience of them thus unfolds in time, but is not straightforwardly linear or narrative. As pieces of music, they might be compared to mobile sculptures: experienced in time, yet atemporal in essence. Like Piet Mondrian’s spiritual journey, Webern worked towards the amalgamation of the irrational and rational.

To some music scholars, placing the work of Young-Sower beside that of Webern will seem like sacrilege. The latter’s work is the foundation stone of the serialist tradition associated with the most profound achievements of high modernism; the former resembles the accidental encroachment of a New Age traveler through the astral plane into the field of reductive drone music. The extraordinary complexity of Webern and the structural simplicity of Young-Sower might seem diametrically opposed in terms of their form and their status. Nevertheless, they are surprisingly aligned in their objectives.

Both aim for an attunement to the eternal constellation of tones, and for liberation from the landscape of historical time. Here spatial metaphors become important again. Frankfurt School philosopher Günther Anders proposed a theory of listening according to which the essential characteristic of music is spatial: a listening person does not exist in the world, but in music. This phenomenological line of inquiry led him to characterize this type of existence as a list of qualities:

That one falls out of the world; that one is somehow somewhere nonetheless; that, even in this hiatus, one remains in the medium of time; that in face of the other reality, one’s own (personal, historical) life becomes imaginary; that it becomes a mere interstice between the situations of being in music; that one no longer is oneself; that one is transformed; that one needs to return to oneself.6

The connection between consciousness and resonance leads us to a composer whose work bridges New Age spiritualism and the traditions of classical composition. Pauline Oliveros’s celebrated practice of “deep listening” is an attempt to reach the most profound resonances through immersive, conscious attention to aural environments. Oliveros always stressed the difference between her method of active listening and meditation, but the influence of alternative spiritual traditions is prevalent in her work. Her exercises and text scores written for multiple performers foster forms of intersubjectivity, while several of her works make room for telepathy or sounds that cannot be “heard” in a conventional sense. Angels and Demons (1980) is characteristic of this:

Angels represent the collective guardian spirits of this meditation.

Demons represent the individual spirits of creative genius.

Angels make steady, even, breath-long tones which blend as perfectly as possible with the steady, even, breath-long tones made by other Angels.

Demons listen inwardly until sounds are heard from their own inner spirits.

Any sound that has been heard inwardly first may be made.

During the course of this meditation, Angels may become Demons and Demons may become Angels.

Begin by just listening for a few minutes until the spirits move.7

The musicians who perform the role of Demons attend to their inner resonance, while the Angels create a shared space. The different roles can be assumed at will, and so the composition stages a social structure which is fluid and non-prescriptive. A life fulfilled at one moment by the expression of inner spirits can in the next return to creating a space in which other “geniuses” can articulate their individuality:

The Demon is listening inwardly so that there has to be a global attention to the imagination. And then expressing out of that. But you have to be open to your imagination to receive that message. And in the Angel part, there’s attention to what’s going on outside, and blending with it as perfectly as possible, which is also a focus. But, in the course of this global appreciation of what’s going on, the message may come to change.8

Oliveros confessed that this composition arose from a failed attempt to create a tuning meditation exercise, which was constantly being disrupted by the need for individuals to express themselves. Angels and Demons offered space for that need while preserving the path towards harmony. The composer observed that, in the end, all the participants would become Angels as the expressive demands of the Demon proved to be exhausting.

Improvisation and self-expression—which manifest the body in time—are introduced only so that the Demons can come to understand that their destiny is to join the Angels in creating an ahistorical realm of spiritual perfection. It’s no coincidence that Oliveros and Webern share this interest in angels. Like the hero/ine of Balzac’s novel, they are genderless creatures that transcend binary oppositions.

Walter Benjamin famously wrote that “ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars.”9 A similar set of relations can be established between the miniature worlds of Webern and the expansive aural spaces of Oliveros. It is striking that, for the latter, it is compassion—often aided by immersion in the deserted natural landscapes of Texas and New Mexico—that opens an individual to the experience of deep listening. Also based in New Mexico, the poet Mei-mei Berssenbrugge makes similar claims in her extraordinary A Treatise on Stars (2020). In a universe structured through resonance, she connects soundwaves with the light that comes to us from the stars, affirming a form of life tuned to the messages coming from the cosmos: “Tones entering my cells transform into feeling, an awareness of two worlds at once. / I send back my thought, picture, feeling, and together we form new vibrations of knowledge that had been dormant in me.”10

The “tuning” in this example creates a new sound space in which tones can be channeled and coordinated. Like Oliveros, Berssenbrugge builds a communal, aural world mediated by angelic forces. These constellations are not objects—like Webern’s perfectly self-contained constructions—but dynamic configurations of resonating tones.

-

Meredith L. Young-Sowers, Agartha: Journey to the Stars (Stillpoint Pub, 1984). ↩

-

Rudolf Steiner, “Music, the Astral World and Devachan,” in Music, Mysticism and Magic: A Sourcebook ed. Joscelyn Goodwin (Arcana, 1986), 254. ↩

-

Quoted in Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, “Webern’s Angels: Rilkean Intransitivity and Transcendence in Two Lieder, Op. 8,” Journal of Musicology 32, no. 1 (Winter 2015). ↩

-

Quoted in Pedneault-Deslauriers, “Webern’s Angels.” ↩

-

Honoré de Balzac, Séraphîta, trans. Katharine Prescott Wormeley, Project Gutenberg, available link. ↩

-

Quoted and translated in Veit Erlmann, Reason and Resonance: A History of Modern Aurality (Zone Books, 2010), 325–26. ↩

-

Pauline Oliveros, “Deep Listening Pieces,” available link. ↩

-

Pauline Oliveros, interview by Tina Pearson, “Angels and Demons,” Musicworks, no. 31 (Spring 1985): 5. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (Verso, 1999), 34. ↩

-

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, “Singing,” in A Treatise on Stars (New Directions, 2020), 81. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776745/angels-and-demons

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.