Listen to everything

Sanna Almajedi

Sanna Almajedi is a curator and writer currently serving as Performance Curator at e-flux. She co-curated Publishing Against the Grain–which was produced by Independent Curators International and toured institutions including Zeitz MOCAA and CCA, Lagos–and more recently curated Babel at SARA’S / Dunkunsthall and Bricks of Memory, Fragments of Home, an online exhibition for White Columns.

Research Title Listen to everything

Category Essay

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Sanna Almajedi

Listen to everything all the time and remind yourself when you are not listening.

—Pauline Oliveros

Spirit communication requires that we hear beyond the normal range of the senses—using a method that Pauline Oliveros called “deep listening” to attend to the sounds of what is absent.

In July 1959, the painter and film producer Friedrich Jürgenson was recording a finch on his tape recorder when, upon playback, he realized that he was hearing the voice of his deceased mother. In this moment, he continued a long association of séances with new technologies for recording and broadcasting the sound of absent people and things.

In the late nineteenth century, music was a vital part of séances. Spiritualists were captivated by the idea of self-playing instruments—pianos with keys pressed down by invisible hands, accordions and trumpets floating as if guided by spectral forces—as evidence of spirits. At the turn of the century, the spread of record players and radio created a new era in which it was normal that music should be disembodied, travelling through space and time without attachment to the bodies that produced it. As musical séances lost their mystery, the airwaves introduced new possibilities for connecting with the beyond.

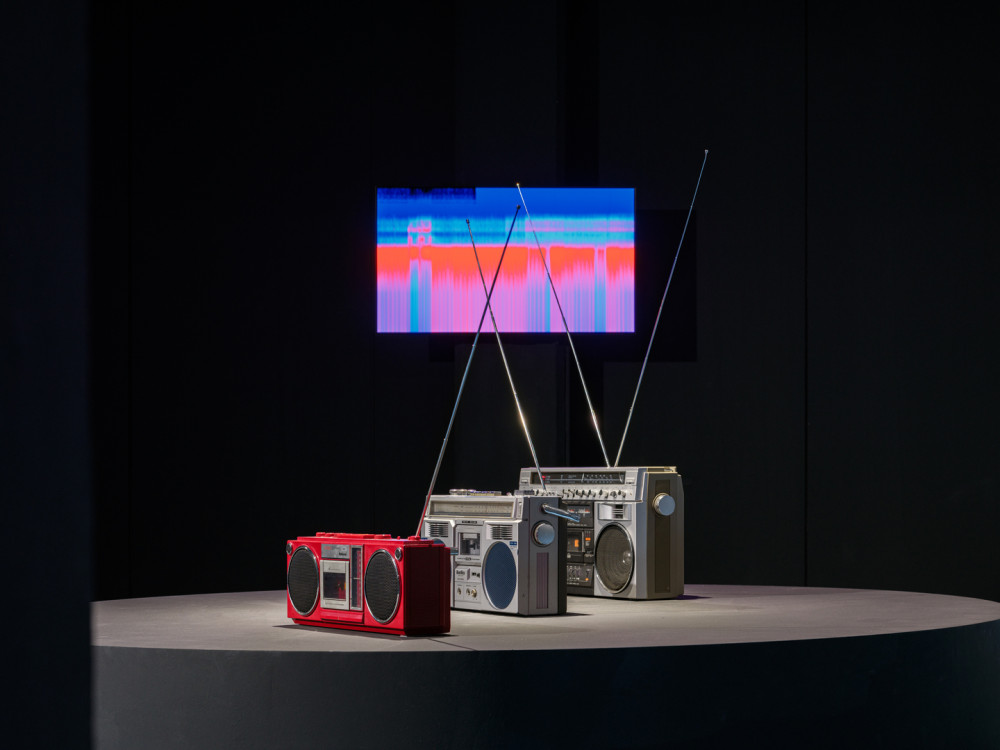

After Jürgenson heard his mother’s spirit speaking to him, he published his research into ways of communicating with the beyond in Rösterna från Rymden (Voices from space). Initially, Jürgenson used a tape recorder and a microphone: he would ask questions and wait for a response, then listen back to the recording at a lower speed to hear the spirit’s voice. Later, on the advice of one of the spirits, he began using a radio to conduct these séances, settling on the ideal frequency of 1485.0 kHz (now known as the Jürgenson Frequency).

The psychologist Konstantīns Raudive, infatuated with Jürgenson’s findings, went on to develop his own methods, recording over 100,000 recordings and coining the term Electronic Voice Phenomenon to describe the apparently paranormal voices or sounds that emerge in recordings. Today EVP is commonly used by ghost hunters and artists alike.

Artists Carl Michael von Hausswolff and Aki Onda adopted the radio to produce séances in which energy is shared between spirits and audiences through electromagnetic soundwaves. Hausswolff’s Get Down With Me was recorded during a live concert at Cafe Oto in commemoration of his friend and collaborator Peter Rehberg, aka Pita. This piece blends drone sounds with a Tibetan kangling flute and EVP recordings conducted in an abandoned night club after Rehberg’s death. Upon playback, Hausswolff picked up on the words “get down with me,” which he connected to Pita’s 2002 record Get Down.

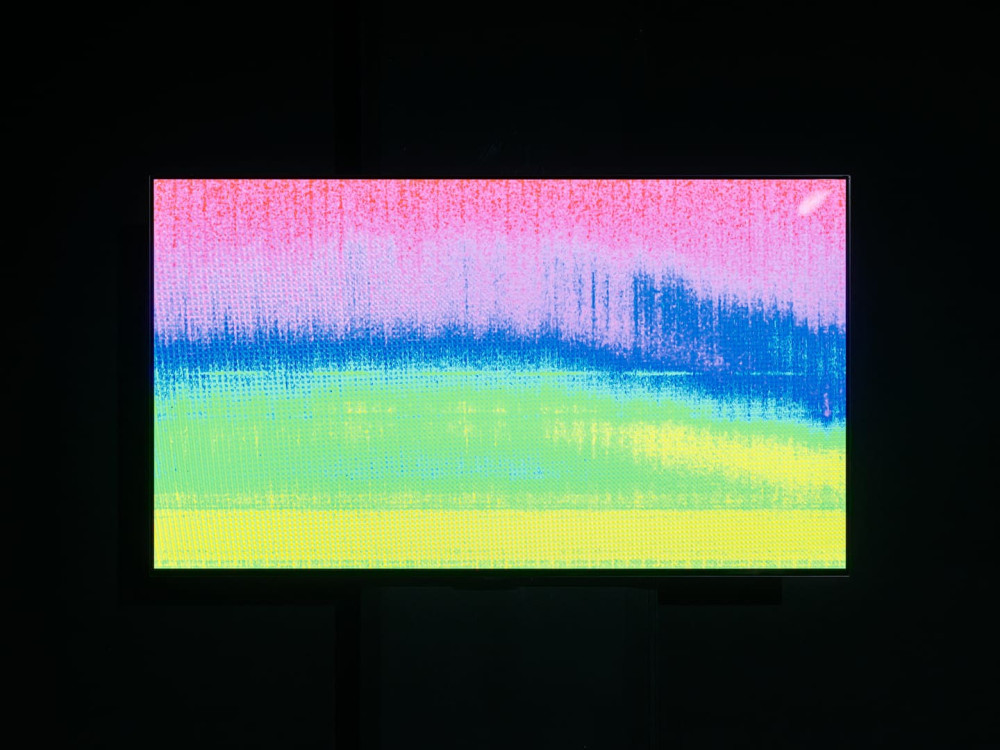

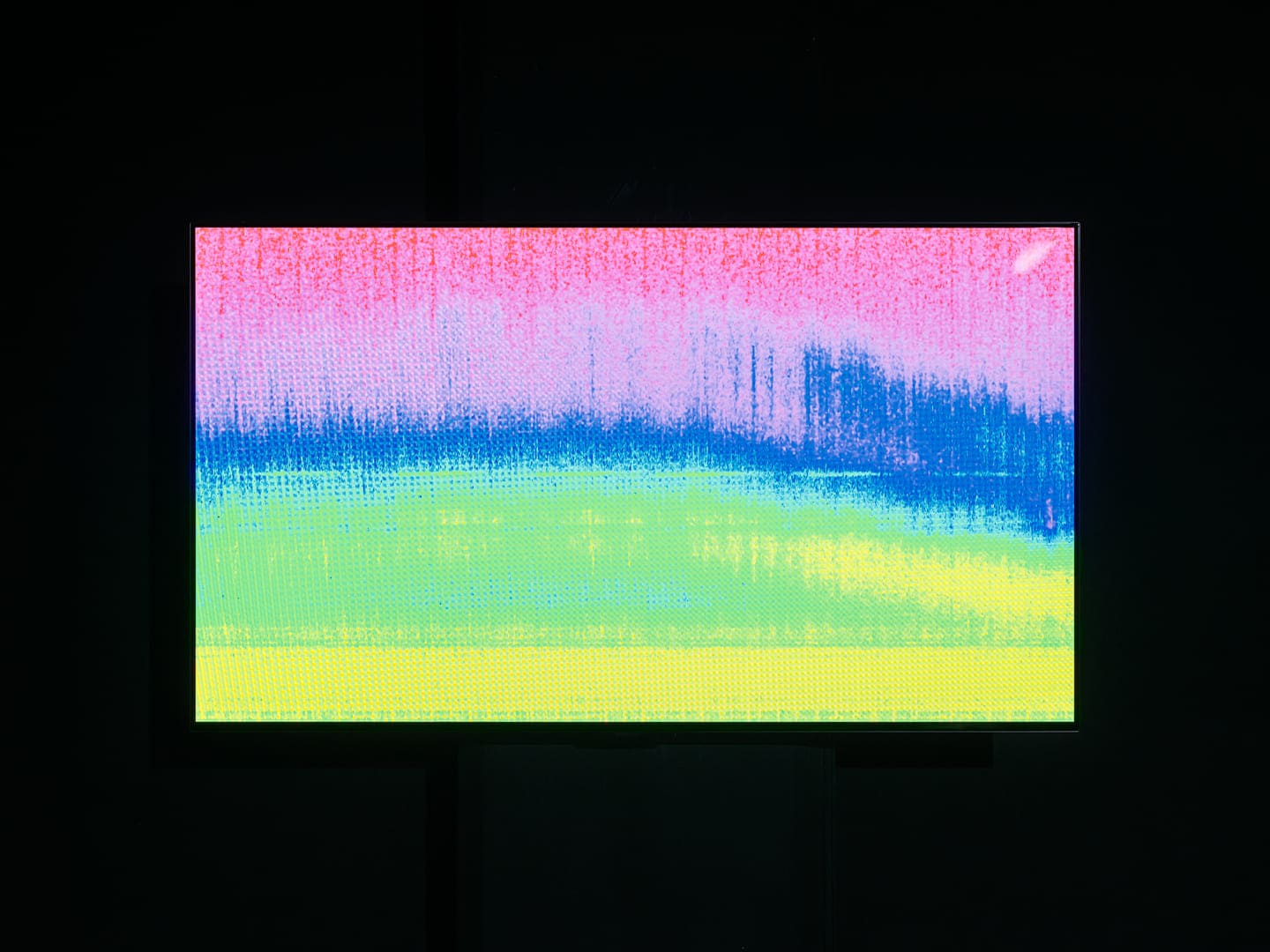

Onda’s Nam June’s Spirit Was Speaking to Me was more of a chance encounter. When Onda was visiting the Nam June Paik Art Center in 2010 to perform a series of concerts, he was surrounded by the work of an artist with whom he felt a close kinship. While he was at his hotel room in Seoul shuffling between radio stations, he found a station that had a cryptic “submerged” voice which he started recording. This was the first time that Paik made contact with Onda.

This was the beginning of a series of séances that Onda conducted around the world to channel Paik’s spirit. Paik himself was fascinated by shamanism and incorporated shamanistic rituals into his concepts and performances. Upon the passing of George Maciunas in 1978 and Joseph Beuys in 1990, Paik drew on the rituals of mudang shamanism to commemorate his friends. In these performances, Paik draws a parallel between the Fluxus happenings that he is known for and Korean exorcism rituals, both of which rely on audience participation. During exorcisms, mudangs ask the audience to take part in the rituals, echoing Fluxus performances that blur the line between artist and audience.

Commemorating a family member, friend, or lover is perhaps the most familiar of all spiritual rituals, in any culture or capacity. In Annea Lockwood’s For Ruth, she commemorates her longtime partner and collaborator, Ruth Anderson, with a tribute that takes us on a journey of love, grief, and presence. Lockwood creates a sonic love letter that combines recorded phone conversations between Lockwood and Anderson with field recordings from places special to the couple; we can hear birds chirping and water running in the background while Lockwood and Anderson exchange words and laughter. In doing so, Lockwood recreates the intimate acoustic relationship the couple once shared, using sound to conjure the texture of their life and to emulate the enduring presence of love beyond death.

In common with many of the works included in the Sound Room at the Nakwon Sangga, For Ruth alludes to Buddhist traditions in which music, voice, and ritual are tools for spiritual transmission and healing. The kangling played by Hausswolff, for instance, is a Tibetan instrument made of a human leg bone and used in ritual contexts to summon spirits and guide our consciousness through the realm of the dead. Other instruments like bells, drums and mantras are used to induce a trance state, a practice integral to Buddhism. This practice is not merely used to establish an atmosphere but to create the conditions for contact with the dead. While these practices remain embedded within their specific cultural and religious context, they continue to provide a vital model for artists devoted to sonic communion between our living world and the spirits that surround us.

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.