Cinema and Séance

Lukas Brasiskis

Lukas Brasiskis is Curator of Film & Video at e-flux; one of the three artistic directors of the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale; and co-curator of the 14th Shanghai Biennale (2023–24). He holds a PhD in Cinema Studies from NYU and writes and teaches about moving-image art.

Research Title Cinema and Séance

Category Essay

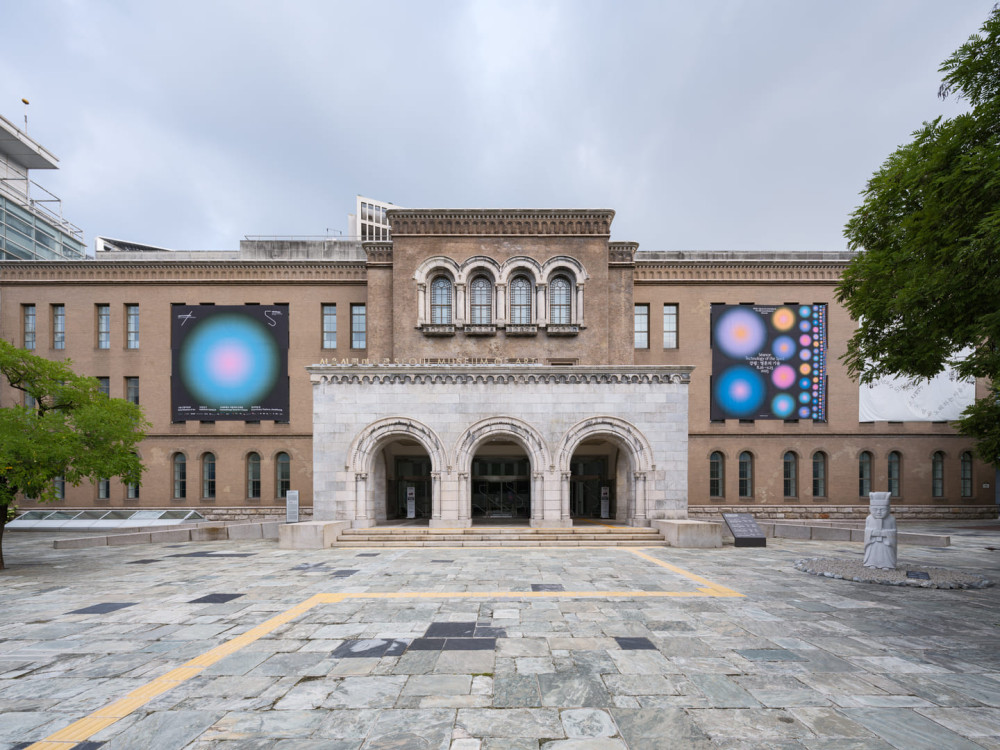

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Lukas Brasiskis

The First Séances

The desire to communicate with the dead is as old as human civilization: woven into myths, rituals, and spiritual traditions across cultures. With the advent of modernity, this impulse took on a new form with the rise in popularity of spiritualism (or spiritism, as it was known in parts of Europe). Central to the movement’s appeal was the promise that followers would be able to converse with the dead through the operation of a medium. This essay reflects on the degree to which this promise was shared with two other cultural phenomena of the era: cinema and psychoanalysis.

By the 1880s, an estimated eight million people worldwide were participating in spiritualist séances. In dimly lit parlors, through rapping, table turning, automatic writing, and other techniques aimed at inducing trance states, mediums invited the deceased to “speak” to the living. Séances typically offered both consolation and spectacle, serving as therapy and entertainment; as scholar Molly McGarry writes, the movement filled a void in nineteenth-century society left by the ascent of industrial capitalism.1 As the reassuring certainties of religious orthodoxy gave way to a mechanistic and empirical worldview, spiritualism provided a new means of navigating the tensions between rationalist modernity and the human desire for answers to metaphysical questions.

Psychoanalysis—sessions of which were, at the beginning, sometimes referred to as “séances”—emerged from the same historical pressures. The migration of the working population from rural areas to industrial cities, where they were subject to a new temporal regime based on factory hours rather than diurnal rhythms, disrupted people’s perceptions of time and alienated them from their bodies and environments. This gave rise to new psychological disturbances: fatigue, anxiety, hysteria, and other “nervous disorders” that confounded conventional medicine.

In its early forms, psychoanalysis can be understood as a response to the disorientation of the modern subject. Indeed, the therapeutic methods of its first practitioners sometimes drew on the techniques of spiritualist séances. The psychotherapist Pierre Janet utilized automatic writing, induced trances, and even designed a mechanical “writing machine” modeled after the planchette devices favored by spiritualists to explore dissociation and subconscious automatisms. Sigmund Freud himself initially used hypnotism and trance states, methods he learned from Jean-Martin Charcot, but soon abandoned them due to their inconsistent therapeutic outcomes and his own limited effectiveness as a hypnotist. Freud and others refined these techniques, further stripping them of any supernatural association and recasting them as scientific, clinical practices for investigating the unconscious through methods such as dream interpretation and free association.

Transference—the patient’s unconscious projection of repressed feelings and desires onto the analyst—became a central concept within the psychoanalytic séance, emphasizing the analyst’s role as an active participant in the therapeutic process. Jacques Lacan later reconceptualized transference through the lens of structural linguistics, understanding it as an intersubjective dynamic between patient and analyst. He famously argued that the unconscious is structured like a language, meaning that repressed content emerges indirectly through phenomena including slips of the tongue. Transference thus operates as a structured encounter with material that resists direct symbolization, underscoring its pivotal role in interpreting the elusive operations of the unconscious.

Without suggesting a direct causal link between psychoanalysis and spiritualism, one can observe that psychoanalysis effectively reconfigured the séance as a clinical and secular practice. Whereas the spiritualist séance sought communication with spirits from a metaphysical beyond, psychoanalysis aimed to make contact with the realm of the unconscious. Rather than channeling the voices of the dead, analysts gave voice to what Freud called “the return of the repressed.”

This structural comparison between spiritualist and psychoanalytic séances provides a framework for a third use of the term, introduced by the emergence of cinema. The French word “séance,” from which the English usage derives, simply means “a sitting.” As the term aptly described both spiritualist gatherings and psychoanalytic sessions, so it captures the experience of sitting with others in a darkened theater to experience the flickering projection of images that mechanically conjure presence from absence.

Do You Believe in Ghosts? Derrida’s Cinematic Séance

In Ken McMullen’s film Ghost Dance (1983), Jacques Derrida famously remarks that “cinema plus psychoanalysis equals a science of ghosts.” When the actress Pascale Ogier asks whether he believes in ghosts, Derrida pauses before replying, “You’re asking a ghost whether he believes in ghosts.” The witty response of Derrida—now twenty years dead, but still talking to us through the medium of film—underscores cinema’s inherent spectrality. His formulation thus bridges the psychoanalytic and the cinematic séance, emphasizing that both are structured around the return of something physically absent and yet still perceptible. By positioning himself as a ghost, Derrida highlights the uncanny logic of cinema (and other technologies capable of mechanical reproduction): figures onscreen are both present and absent, alive and dead.

In a 2001 interview, Derrida emphasized that the cinematic séance brings viewers face to face with the return of the repressed. The medium is thus uniquely suited to preserving and reanimating traces of the past, creating an uncanny space in which the dead may appear more alive than the living.2 Derrida expands on this idea in the introduction to Ecographies of Television, explaining that each time he watches Ghost Dance he is haunted by the way Ogier (who died just two years after the film was shot) returns to ask if he believes in ghosts.3 For Derrida, this technological repetition underscores cinema’s spectral nature.

Yet how accurately does this “science of ghosts”—this cinematic transference—map onto other forms of séance? Derrida suggests that, as with psychoanalysis, it operates through a double projection: first, the literal projection of images onto the screen, and second, the viewer’s psychological projection of their unconscious desires and fantasies onto those images. Through this process the viewer is confronted by their own unconscious.4 As Derrida wryly observes, “A screening séance is only a little longer than an analytic one. You go to the movies to be analyzed, by letting all the ghosts appear and speak. You can, in an economical way (by comparison with a psychoanalytic séance), let the specters haunt you on the screen.” In other words, the cinema becomes a space where the specters lurking in one’s psyche can safely—and much more cheaply—return to consciousness.

While Derrida foregrounds the spectral dimensions of cinema as revealed through this double projection, another way of thinking of the cinematic séance emphasizes not what is absent but what is present.

Collective Dreaming: Edgar Morin’s Cinematic Séance

This form of presence is affective and participatory, and was vividly expressed by Edgar Morin in his seminal 1956 book The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man. Rather than focusing on haunting absences, the sociologist and filmmaker approaches cinema as a shared ritual of collective dreaming. This concept is markedly different from Derrida’s emphasis on spectrality, yet complements its insight into cinema’s psycho-emotional potency.

Morin proposes that, in cinema, “the absence of practical participation establishes an intense affective participation: veritable transfers take place between the soul of the viewer and the spectacle on the screen.”5 This notion foregrounds what Morin identifies as cinema’s fundamental structure: the projection-identification complex. This is a reciprocal dynamic wherein the viewer both projects their unconscious desires, emotions, and fantasies onto the screen and, in turn, internalizes those images. Projection is thus “built into our very perception,” while identification occurs when “the subject, instead of projecting himself onto the world, absorbs the world into himself.”6

Morin’s loop echoes Derrida’s doubled consciousness, yet it differs significantly in emphasis and outcome. While Derrida highlights the disquieting spectral absences and the return of the repressed in cinema, Morin underscores an affirmative emotional process whereby affective projection creates a richly immersive psychic space. Morin’s viewer, much like Derrida’s, is consciously aware that the spectacle is fiction, yet actively suspends their disbelief in order to emotionally inhabit the cinematic world. Physically unmoving yet psychically open, they enter a state of heightened receptivity in which the material reality of the theater recedes and an imaginary space of collective reverie emerges. Morin frames this not as a source of anxiety, but as the source of cinema’s pleasure, enchantment, and communal emotional resonance. This aligns with Felix Guattari’s claim that cinema uniquely mobilizes affective multiplicities, resisting psychoanalysis’s linguistic constraints.7

Such affective immersion transforms the screen into a site of psychic transference, effectively reviving the logic and practice of animistic belief systems. Morin explicitly links the modern cinematic experience to magical thinking, even equating cinema with an animist perception of the world. Within the theater, everyday images and ordinary objects are treated by viewers as if they are alive and possess souls. Morin argues that this condition—“isolated, but at the heart of a human environment, of a great gelatin of common soul, of a collective participation”8—creates a uniquely favorable situation for emotional and psychic exchange. Comparable to a trance state or a sacred rite, cinema renders the sitter highly susceptible to emotional suggestion and collective identification.

This emotional engagement positions the modern viewer as an active participant in a contemporary magical ritual, endowing moving images with affective and spiritual vitality. Between the image and the double, Morin writes, “is a magic in its nascent state,” subjectivized as sentiment.9 Crucially, cinema’s animistic enchantment arises in the tension between rational awareness and affective absorption: in the ambivalent experience of treating images as living beings despite knowing they are not. The cinematic séance thus becomes a uniquely powerful technique for restoring emotional depth and spiritual resonance to a world that has been disenchanted by rational materialism.

Filmmakers such as Apichatpong Weerasethakul exemplify and extend Morin’s insights by explicitly engaging animistic and spiritual cosmologies in their work. As films like Tropical Malady (2004) and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) show, Weerasethakul’s cinema embodies a distinctly performative realism, characterized by a porous boundary between human and nonhuman worlds and an animistic logic in which spirits, humans, animals, and landscapes interact fluidly. The representation of landscapes in his films is deeply rooted in Thai folk beliefs that imbue the natural world with life and agency and populate it with spirits who carry stories, traumas, and repressed memories, notably those related to Northern Thailand’s turbulent political history.

Tropical Malady, for instance, follows a soldier’s gradual dissolution into the jungle around him, unsettling and eventually erasing the boundary between rational, individuated consciousness and an enchanted, animistic perception of the world. The soldier—with whom the viewer comes to identify—becomes a creature existing between the human and more-than-human realms. Similarly, in Uncle Boonmee, the permeability between the living and spirit worlds is portrayed through calm, matter-of-fact interactions between human characters and their deceased loved ones, who return as ghosts that are familiar in, and integral to, everyday existence.

Weerasethakul’s understated realism reminds viewers that phenomena that might seem extraordinary to them are conventional to rural Thailand. The effect is to encourage empathy and identification across cultures rather than to other or exoticize. Morin’s projection-identification dynamic is clearly at work: Weerasethakul’s films demonstrate cinematic séance’s capacity to articulate culturally specific realities in a resonant way. Through his careful attention to historical and ethnographic detail, the Thai director actualizes Morin’s vision of cinema as a process of animistic enchantment.

Though distinct in emphasis, Morin’s and Derrida’s conceptions of the cinematic séance both acknowledge the doubleness of the cinematic experience: the simultaneous sense of presence and absence. While Derrida foregrounds cinema’s haunted structure, organized around absences and the spectral returns of repressed elements, Morin emphasizes how cinema enchants the material world, drawing viewers into an emotionally affective, collective dream. In Morin’s view, the cinematic séance operates not by confronting us with what is absent, but by intensifying the presence of something larger than ourselves.

Technology of the Spirit: Art’s Emancipatory Potential

It is indisputable that cinema no longer occupies the central cultural position it held throughout the twentieth century. Nonetheless, we remain immersed in moving images. We inhabit a world shaped by spectral interactions mediated through digital screens and networks, in which Derrida’s “technological ghost” has become an everyday reality. The texture of our historical moment is characterized by intimacy at a distance, proximity without physical contact, and instant connectivity devoid of emotional empathy: these are the instruments of digital capitalism and its algorithmic logics, machine-learning technologies, and deepening sociopolitical crises.

In this context, Derrida’s and Morin’s different yet complementary takes on the cinematic séance might suggest new ways of renewing those bonds to the natural and social world that have been cut by the dominant technocratic paradigms of rationalized modernity. As forms of emotional and intellectual connection with what has been lost, séances might thereby serve as a laboratory for imaginative potential, radical care, and the reclamation of ancestral knowledge. By challenging the prevailing limits on what humans can sense in the world, what is remembered, and who gets to decide, séances are recast as an emancipatory practice in which participants must reframe their relationships not only with the dead but also with the living.

-

Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America (University of California Press, 2008), 25–26, 31–34, 41–42. ↩

-

Antoine de Baecque and Thierry Jousse, “Cinema and Its Ghosts: An Interview with Jacques Derrida,” first published in Cahiers du Cinéma, and later, in a translation by Peggy Kamuf, in Discourse 37, no. 1–2 (Winter–Spring 2015). ↩

-

Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, Ecographies of Television: Filmed Interviews, trans. Jennifer Bajorek (Polity Press, 2002). ↩

-

Félix Guattari similarly emphasizes cinema’s distinctive capacity to engage the unconscious through heterogeneous semiotic channels, describing cinema as a “gigantic machine for modelling the social libido,” whose machinic qualities partially evade psychoanalytic reductions to linguistic signifiers. Félix Guattari, “The Poor Man’s Couch,” in Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972–1977, ed. Sylvère Lotringer (Semiotext(e), 2008), 258. ↩

-

Edgar Morin, The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man, trans. Lorraine Mortimer (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 95. ↩

-

Morin, The Cinema, xxiv–xxv. ↩

-

Guattari argues that cinema produces complex “constellations of affects” through sensory multiplicities, emphasizing its animistic and emotional potency. Unlike psychoanalysis, which attempts to stabilize and domesticate desire, cinema maintains openness through polyvocal semiotic flows, enhancing collective emotional resonance. See Guattari, “The Poor Man’s Couch,” 262–65. ↩

-

Morin, The Cinema, 97. ↩

-

Morin, The Cinema, 67. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776774/cinema-and-s-ance

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.