Princess Bari Hwang

Rushi

Hwang Rushi, a leading scholar in Korean and Asian folk traditions and shamanic rituals, earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism and broadcasting from Ewha Womans University and completed her doctorate in Korean literature at the same institution, with a dissertation titled A Study on the Shaman Ritual Drama. Since 1976, Hwang Rushi has conducted extensive fieldwork on Korean shamanism, and beginning in 1988, she expanded her research to include comparative studies of Asian shamanic traditions through on-site investigations in Japan, Myanmar, Taiwan, and Vietnam. From 1988 to 2016, she served as Professor in the Department of Media Literature at Catholic Kwandong University and is now serving an honorary professorship. In 2005, she authored both the application and video script for the Gangneung Danoje Festival’s inscription as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. She went on to serve as the eighth President of the Society of Korean Oral Literature in 2007 and as a Cultural Heritage Committee Member under the Korea Heritage Service in 2011. Her major publications include Korean Shamanism and the Mudang (Moonumsa, 1992), Stories of Our Shamans (Pulbit, 2000), Jindo Ssitgimgut: National Intangible Cultural Heritage No. 72 (Hwasan Munhwa, 2001), Paldo-gut (Shamanic Rituals Across Korea) (Daewonsa, 2011), and The Protagonists Behind the Stage (Wings of Knowledge, 2021). In recent years, she has turned her attention to reimagining shamanic rituals in theatrical form. She has adapted the representative shamanic myth Danggeumaegi for the stage and directed performances such as Gut with Us and Dance, Dano, and Divine Ecstasy.

Research Title Princess Bari

Category Essay

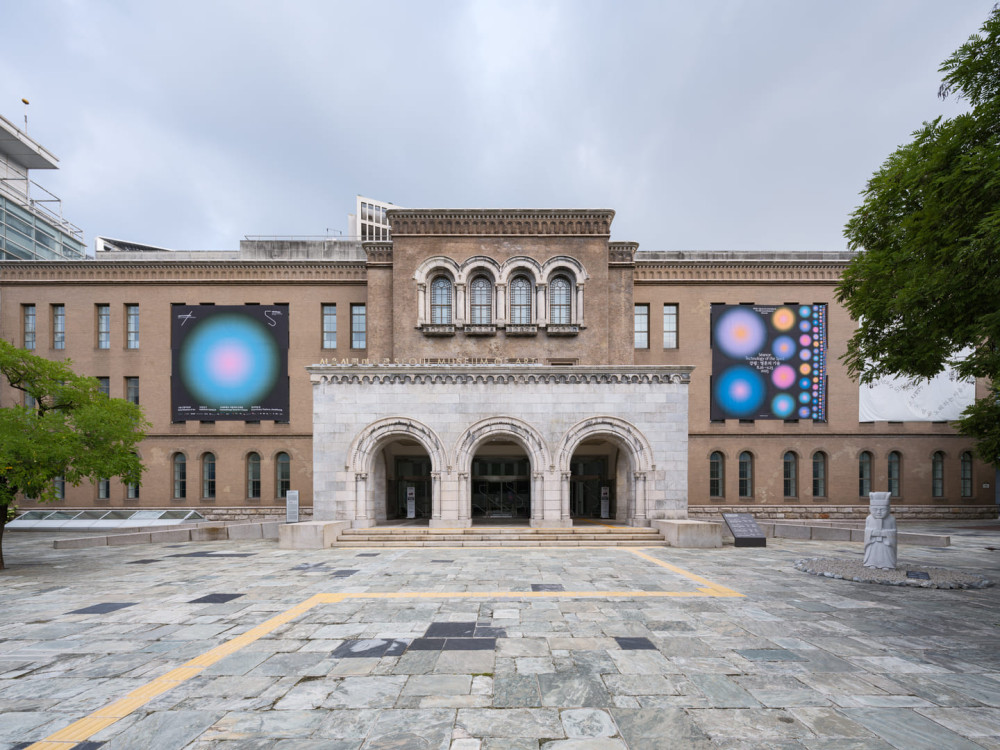

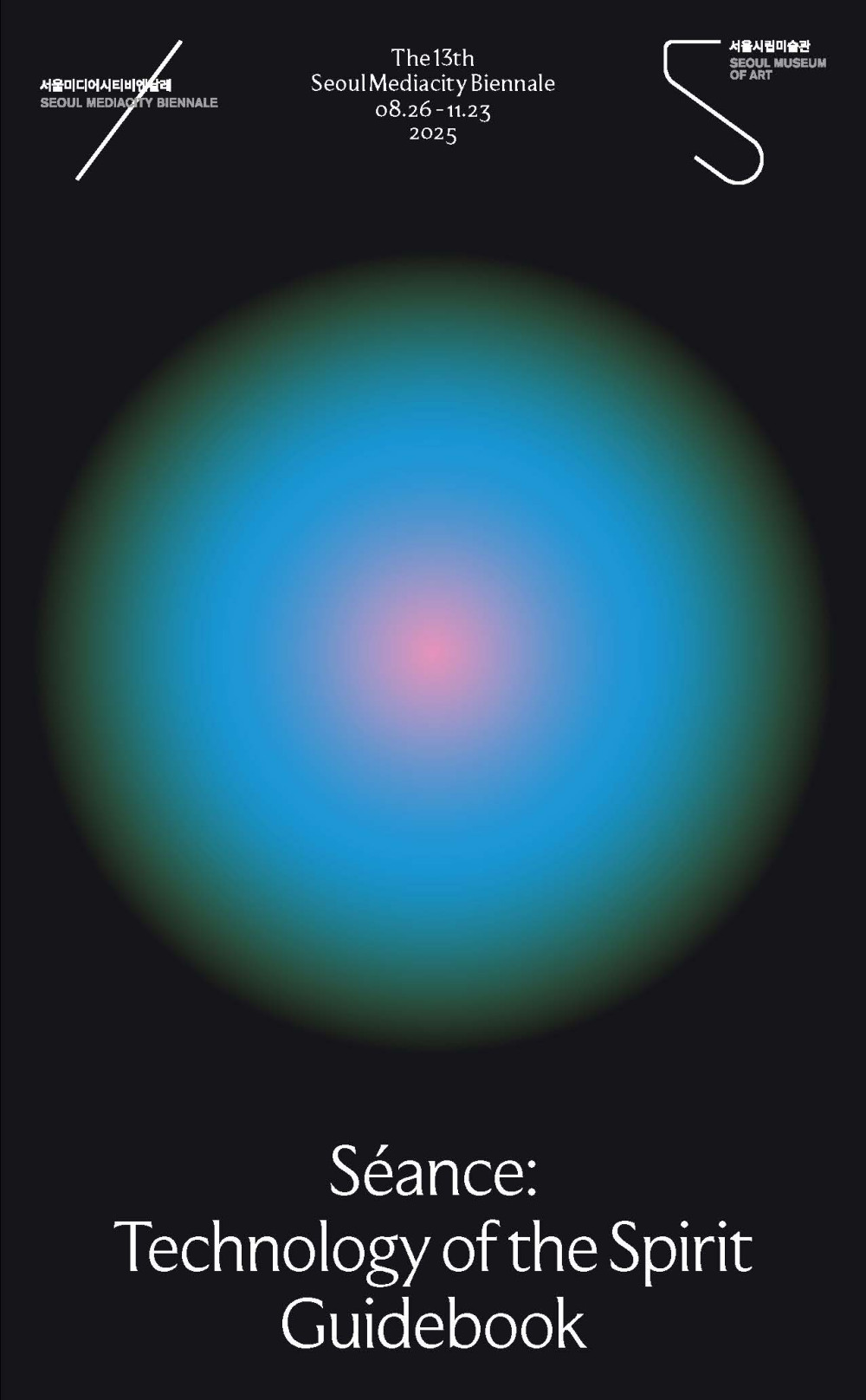

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Hwang Rushi

OBSERVER: Unravel the seven knots around the garments.

Put the flower of vitality into their breath and their bones.

Restore the warmth of their flesh and the brightness of their sight.

Pour the water of life into their mouths and let it flow forth.

The royal couple, on the same day, in the same hour, are revived.

THE ROYAL KING: I fell into a deep slumber.

Did I gather to see the ocean or the flowers on the mountain?

OBSERVER: No, they did not come to see the ocean or the flowers.

It is a grand funeral procession for you,

who passed away on the same day, in the same hour.

The seventh daughter, Princess Bari, journeyed three thousand li to fetch the medicinal water

and on the same day, in the same hour, brought it back and restored you to life.

…

SHAMAN: Oh, you woeful departed, who died before and after!

Listen closely with your decayed ears and mouths.

Remember it well and recite it to the Bodhisattva.

Today is the day you follow Princess Bari to the land of Sukhavati.1

Princess Bari in the Jinogigut in Seoul2

In the evening, the Jinogigut funerary ritual that started in the morning is coming to an end, and it is time for the deceased to say goodbye to his family. In front of the gutdang shrine, there are twelve gates that the deceased must pass through on his way to the afterlife. The family, who have greeted the deceased at the shrine all day and have cried and cried, are now sitting on the floor, exhausted. A shaman in gorgeous attire sits on a chair with a janggu drum in front of her. Large, heavy hair adornments hang from the shaman’s neck, and she wears a silver hairpin decorated with seven treasures and a dangling hairpin. She wears twelve petticoats on top of another traditional square-shaped petticoat made by weaving tree branches together. Over that, she wears a red silk skirt and a dangui ceremonial garment. It is the attire of a princess in ancient times. The shaman, who gracefully hangs a ribbon and places a fan and bells beside her, begins the ritual. The family members, shaking off their tiredness, kneel before the shaman and listen attentively.

Your majesty, your majesty, Gongsim is the principal deity of our ritual, and the Namsan mountain is her origin.3

The shaman sings the story of Princess Bari while striking only one side of the drum.

King Eopbi ignores the fortune teller’s prophecy that he will have three sons if he waits a year to marry but seven daughters if he marries this year. The prophecy proves to be true, and King Eopbi is disappointed again and again in his desire for a son. Finally, when the seventh daughter is born, he names her Princess Bari—meaning “abandoned, discarded, thrown away”—puts her in a jade box, and sets her adrift far, far away down the river. So this is the story of the princess who was abandoned as soon as she was born and grew up without ever knowing her parents.

Having offended the heavens with this action, King Eopbi fell gravely ill. The fortune teller declares that one of their children must be sent into the underworld to retrieve a special medicinal water. The six daughters at court refuse this task, and so a command is issued to find Princess Bari, who is then reunited with her parents. But the joy of this reunion is cut short when she learns of their situation. She agrees to risk her life by going to the underworld, saying, “I owe my parents for giving me life, even if they did not raise me.”

But how can a frail young woman go to the afterlife? She must dress as a boy. After going through many hardships to enter the underworld, she finds the nine-foot-tall Mujangseung guardian spirit of the water of life.4 Princess Bari introduces herself as a prince, to which the Mujangseung says, “How strange. I’ve heard of a princess in that country, but this is the first I’ve heard of a prince. In any case, if you bring me water for three years, wood for three years, and fire for three years, I will give you the healing water.” After working for nine years, the Mujangseung suggests they bathe together. He says, “You bathe up there, and I’ll bathe down here.” But the sly Mujangseung secretly spies on her bathing and hides her clothes. Realizing that she is a woman, the Mujangseung says he will give her the water of life only if she marries him and has seven sons. Princess Bari has no choice but to marry the Mujangseung, and they have seven sons together. One day, Princess Bari dreams that the spoon used by her parents has broken, and interprets this to mean that her father has passed away. She hurriedly returns to the land of the living with medicinal water and the flower of life obtained from the Mujangseung.

But by the time she gets back to save her father, accompanied by her seven sons and her husband, the funeral procession of her father is already underway. Princess Bari halts the funeral bier, gently stroking the body with the flower of life and pouring healing water into the king’s mouth, bringing him back to life. She is then offered half of the country for having saved her parents, but Princess Bari has no desire for the fortunes and honors of this world and chooses instead to ascend as a goddess of the afterlife.

The long story continues through the family’s sobs. Every so often, the shaman strikes the drum, then stops singing and exclaims, “Oh, my! How sad! Today is the day to follow Princess Bari to the land of Sukhavati.” She raises and shakes her bell high in the air. The family members wail, crying out, “Ah-ee-gou, ah-ee-gou,” as if the deceased had only just died. They cry until they are hoarse in the hope that Princess Bari, hearing the shaman’s call, will succumb to pity and come to save the departed soul of the poor deceased. “Ah-ee-gou, ah-ee-gou!”

They believe the grim reaper is standing by, waiting for his opportunity to take the soul, but will the deceased be dragged away to the afterlife by the grim reaper like a lowly criminal, or will they travel under the warm guidance of Princess Bari? Everyone born into this world dies. We are beings destined for death.

There is a Korean saying: “Even rolling in a field of dung is better than death.” Better to be a living dog than a dead lion. So how can we face death, which is so unfamiliar and fearful? The lost souls of the deceased depend on Princess Bari, an ancestral mother goddess who stands at the endpoint of life and saves wandering souls. She is a being worthy of thanks as she gently carries grieving souls to the afterlife with the same devotion with which she saved the parents who abandoned her, the same warmth and compassion with which she soothed the souls she met along the road to the underworld, and with the quiet confidence of having successfully braved a journey into the unknown. Today, Princess Bari is the only salvation and hope for the deceased and the family that loved them.

The Different Faces of Princess Bari

Princess Bari is a charming character who can be interpreted from different perspectives. Firstly, she is a devoted daughter. She epitomizes filial sacrifice in that she saves her father who abandoned her by risking her life to go to the underworld. A comparable figure is Sim Cheong,5 but Princess Bari’s sacrifice is more profound because Sim Cheong’s father, Blind Sim, never abandoned his daughter.

Secondly, Princess Bari illustrates the power of women in a patriarchal society. Princess Bari is abandoned because she was born a girl. Yet she is able to save her father, thereby both highlighting and overcoming the problems of a gender-discriminating society. A Korean folktale that addresses a similar theme—albeit in a more comical way—is The Story of the Farting Daughter-in-Law. When the protagonist’s father-in-law asks what is making her sick, she answers that it is because she does not want to pass wind. He urges her to go ahead, claiming that he understands. But when she farts, it is so powerful that it nearly brings the house down, and he chases her out. On her way to take refuge in her hometown, she enters a competition to pick a pear hanging from a tall tree. With the aid of her amazing fart, she earns a prize of silk and bronzeware. Seeing the treasure, her father-in-law takes her back, saying, “Your fart is a lucky fart.” While one story is tragic and the other farcical, they share a similar premise.

Finally, Princess Bari is the ancestral god of shamans, or the goddess of the underworld. These two different interpretations are connected to the roles of shamans as healers. In the medical history of the Joseon era, shamans were assigned to the Hwal-in Seo public health center. Capable of bringing the dead back to life, Princess Bari is a healing shaman of the highest rank and worshipped by shamans in the Seoul area as the ancestral god of shamanism.

In other regions, she is worshipped as the goddess of the underworld. In this case, Princess Bari is the goddess who guides souls to the afterlife, just like the Inrowang Bodhisattva in Buddhism. She is a being who saves people at the border of life and death, cleansing the sins of the deceased so that they can freely enter the afterlife. Shamans heal both the bodies and minds of sick humans because they believe that the body and soul are connected to each other. Just like Princess Bari, shamans help to cure illnesses and prepare the soul to enter the realm of eternal life.

Bari-degi, an Abandoned Child Reborn as the People’s Princess

The tale of Princess Bari is also known as the myth of Bari-degi, meaning “the one who was abandoned.” The two names have different implications. A princess should be loved and respected, but degi is a suffix that refers dismissively to people of a low status, like a kitchen maid (bueok-degi). The princess became Bari-degi because she was abandoned by her parents, and she was abandoned because she was female. In that sense, Bari-degi is a character created by the contradictions of a male-dominated feudal society. However, the point of this myth is not to reveal an unequal system so much as to prove that the abandoned Bari-degi is the real princess.

The myth begins with Princess Bari being lowered to the status of Bari-degi and ends with Bari-degi being raised to the status of princess. In the process, she overcomes the absurd systems and conflicts of human society and is recognized as a princess of all people. This is the core of the myth.

The family into which Princess Bari was born consists of a father who insists on preserving a patriarchal system and the people who depend on him. The father represents the family, but he is to blame for all of its problems. He ignores the prophecy of the fortune teller, has seven daughters as predicted, and still abandons Princess Bari for not being a son. As punishment for his sins, he falls so ill that Princess Bari has to risk her life by going to the underworld. Bari-degi’s mother passively follows her husband’s orders despite knowing that they are unfair. She fails to correct his unjust behavior and neglects her maternal responsibilities.

Princess Bari’s older sisters are also dependent on their father. They grow up enjoying wealth and honor, but never gain independence nor understand their filial duties. They refuse to go to the afterlife to retrieve the water of life that would save their parents, saying, “We get lost even in the royal palace, so how can we go to the land of Sukhavati?” As cunning characters who care only about themselves, they only ask, “To which son-in-law will you pass down the royal seal?”

The royal court, as an extended version of the family, is no better. Not a single subject offers to journey to the underworld for the king. Their relationship to the king is simply that of superior and subordinate, with the subordinate doing only what the superior orders. Once the power to give orders is lost, the relationships that hinged upon it dissolve. These are the limitations of any authoritarian, patriarchal system, and of feudal society.

However, Bari-degi is not part of this world’s society. Bari-degi was raised by a wandering beggar couple or, according to another version of the story, by animals in the mountains. It is because she was abandoned by the male-dominated, authoritarian society that she is able to grow into her own independent being. After meeting her parents, she decides to go to the underworld out of pure filial devotion, saying, “I don’t owe the country any favors, but I shall repay the favor of being carried in my mother’s womb for nine months.” Although she grows up without anyone to take care of her, she learns and lives by the principles of human decency, which grow from filial piety.

Bari-degi’s growth as an individual is completed by her journey to the underworld. Bari-degi meets many people on this journey and even has a family of her own, forming new relationships in the process. It is significant that Bari-degi has no supernatural abilities and cannot travel to the underworld without help.

But she is a trusting person, and she finds her way to the underworld by asking for help from the people she meets on her journey. Notably, everyone she meets belongs to the working classes. She finds them plowing the fields with oxen, grinding grain, or doing laundry in the stream. When Bari-degi asks for directions, they say, “If you don’t work, you don’t eat, and there is no such thing as a free meal.” So, Bari-degi helps them with their tasks before she asks them for help. She works hard to plow wide fields with one ox and help farmers grind grain. In the middle of winter, she even breaks the ice on a frozen river with a club to do laundry.

She also washes coal until the water runs clear, lays ninety-nine spans of an iron bridge, builds towers, and picks out lice from an old woman’s hair. In this way, she practices self-cultivation and accumulates virtue. Bari-degi becomes a capable worker through solidarity with working people, and she learns to devote herself to others, regardless of who they are, on her way to the underworld.

When she finally arrives in the underworld, she works silently for nine years for the Mujangseung; cutting wood for three years, making fire for three years, and drawing water for three years. It is mundane work, which makes it all the more difficult and arduous. There is nothing to brag about in being good at drawing water, nor any sense of accomplishment in being good at chopping wood, nor praise to gain for making fire. It is simply labor that must be done to survive. When Mujangseung discovers that Bari-degi is a woman, he offers to give her the medicinal water only if she marries him and bears him seven sons. She lives the life of an ordinary woman who works hard and raises one child after another. In this process, Bari-degi becomes a worker trained in labor and a nurturing, maternal figure, and thus becomes a representative of the people.

Although the marriage was coerced, Bari-degi becomes the central figure of the family; when she finally returns home to save her father, her husband and her seven sons all follow her. In the Yeongdong regional version, Bari-degi’s husband, Dong Suja, ascends to the heavens alone, but Bari-degi does not despair. As a responsible matriarch, she carries her sons in her arms and on her back and sets off to save her father. In the Seoul version, the Mujangseung or Mujang Sinseon follows Bari-degi to live in the world of the living. Up until then, Bari-degi had lived abiding by her husband’s will. But just before she departs, he confesses that he cannot live without her because she is the true central pillar of their family and follows her.

By these means, after creating a new family and saving her own parents, Bari-degi becomes a goddess who governs the afterlife. Her husband and seven sons take on supporting roles. This world, centered around Bari-degi, offers an alternative to the patriarchal society dominated by masculine prejudice. Bari-degi personally accomplishes hard tasks, becomes a responsible matriarch, demonstrates solidarity with working people, and gains the respect of her husband. In this world, everyone in the family has a role, and each must work. Bari-degi provides a new model for women by becoming the people’s hope and the people’s princess.

The Power of the Powerless

Princess Bari saves her father without seeking worldly wealth and honor. Instead of inheriting her father’s kingdom in this world, the once abandoned Bari-degi becomes the ancestral deity of shamans (whose rank is the lowest in society) and the goddess of the underworld. Another way of reading this story is that Princess Bari saves her father but receives no credit for it in our world. Assuming that the husband of one of her sisters succeeded the king, the people still regard Princess Bari as their true leader. In this sense, Princess Bari is a history told from the perspective of the defeated. It is the story of a character who seems to lose in life but becomes the true protagonist of history.

Modern society is dominated by power. The current global order is dominated by the United States, which calls itself the custodian of the world order but instigates wars. In Korean society, corruption is endemic. Both reflect an ideology that values power. They talk of love and peace, while preserving a system that revolves around a few powerful people. Modernity is characterized by an inescapable sense of alienation and helplessness. We are told that everything is possible, yet human life has never been treated so cheaply as in the modern era.

Hwang Sok-yong’s 2013 novel Princess Bari updates the story to present its protagonist as a woman who must endure all kinds of suffering and displacement by ideological conflict and racism across modern global society. The novel doesn’t claim to offer a definitive answer to how we might heal a world overrun by war and slaughter, but it contains a humble truth: only those who have endured pain and suffering can truly forgive, embrace their enemies as neighbors, and bring about peace.

As the Korean poet Heo Su-gyeong once wrote, “There is no fodder like sorrow.” Princess Bari is a source of hope for today’s alienated and marginalized people because she is a powerless being who becomes a figure of solace, healing, and support. Out of yearning for the love of the parents who abandoned her, she chose the path of death, only to be abandoned once again. Her life of alienation is likewise a comfort to those who have been betrayed or excluded. The shamanic song of Princess Bari is called Malmi—a noun meaning “the source of all things.” Death is the source of life, and life is the source of death. Standing on the border between life and death, Princess Bari fulfils her life by embracing death.

Power can determine people’s actions, but it cannot move their hearts. Religion and art share a common ground in their ability to move the human spirit. Shamans and artists move the deepest parts of the human heart and soul. Recently, many artists have joined forces with Princess Bari in their efforts to move people’s hearts. Bari’s gift does not lie in the mystical realm, but in embracing the hopes of marginalized people. This is how the strength of the powerless is activated.

-

Princess Bari is one of the most characteristic of the Seosa muga, and has been passed down through a countrywide oral tradition. The version excerpted here was recited in the 1930s by the Seoul-based shaman Bae Gyeongjae and recorded in 1937 by the Japanese scholar Akamatsu Chijō. In addition to its literary value, this record is a significant historical resource, offering insight into regional variations in narrative structure and patterns of transmission. Editors’ note: According to Hwang Rushi’s research, Korean shamanism did not originally distinguish between worlds associated with the afterlife, such as heaven and hell. However, after the introduction of Buddhism to the Korean peninsula, shamanism and Buddhism became closely intertwined. The Seosa muga (epic shamanic songs) often refer to the afterlife as a “paradise” located in the “Western Pure Land,” aligning with the whereabouts in Buddhism of Amitābha’s land, or “Ultimate Bliss.” ↩

-

Jinogigut is a ritual to comfort the soul of the deceased and guide it to dharma, or afterlife. It is referred to by different names and is applied in different circumstances in the various regions of Korea: in most cases, a shaman is brought within a few years after death in order to complete the departure of the dead, and the story of Princess Bari is recited. ↩

-

According to some theories, Gongsim was a royal princess who is revered as an ancestral deity of shamans. ↩

-

In the Seoul and Gyeonggi regions, this character is called Mujangseung, a towering guardian spirit believed to protect the sacred spring of life. In the Yeongdong region, he is known as Dongsuja. ↩

-

The Story of Sim Cheong is a classical Korean novel about filial love. The titular Sim Cheong throws herself into the Indang Sea as a sacrifice so that her blind father can regain his eyesight. This act of filial piety causes her to be resurrected and enthroned as an empress, while her father’s blindness is cured. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776764/princess-bari

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.