Séance: Technology of Disalienation

Elena Vogman

Elena Vogman is a scholar of comparative literature and media. She is principal investigator of the research project Madness, Media, Milieus: Reconfiguring the Humanities in Postwar Europe at Bauhaus University WEimar and a visiting fellow at ICI Berlin.

Research Title Séance: Technology of Disalienation

Category Essay

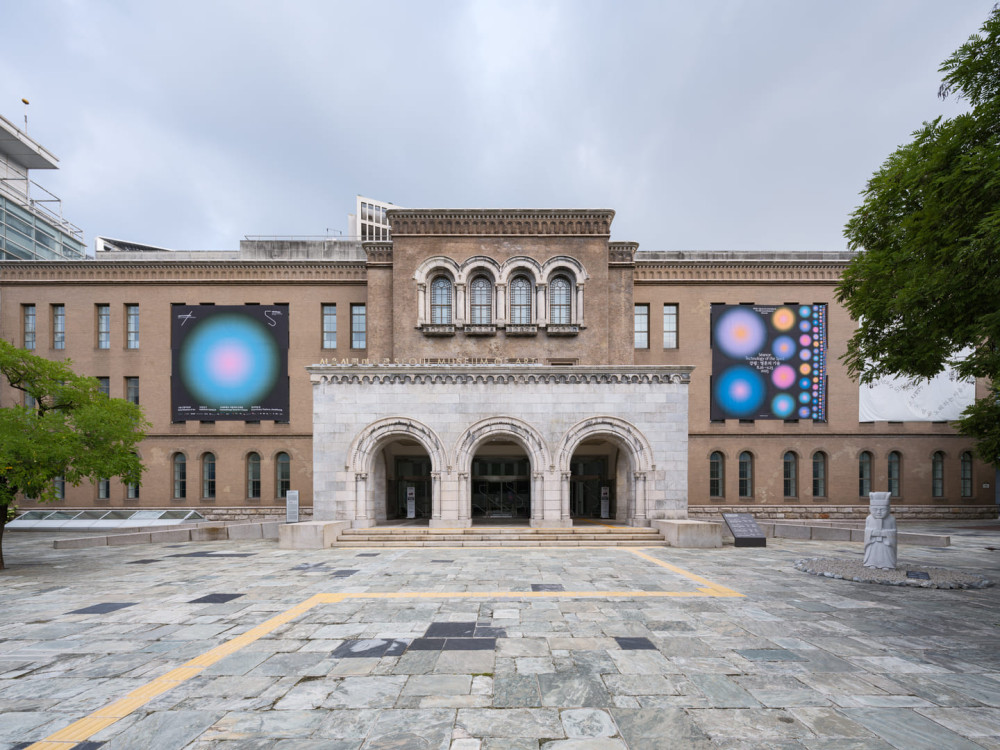

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Elena Vogman

On June 2, 1961, in the French region of Lozère, at the cinema of Saint-Chély-d’Apcher near the psychiatric clinic of Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, a very special séance took place. This screening was organized at the request of François Tosquelles, a militant anarchist doctor in exile who was one of the main initiators of the radical psychiatry movement known as institutional psychotherapy. With an audience composed of psychiatric patients, nurses and doctors, farmers, and local villagers, two films were shown and discussed: The Mad Masters (1955), by pioneer of ethnographic cinema Jean Rouch, and Chronicle of a Summer (1961), by Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin.

The Mad Masters—banned in France shortly after its completion in 1955—features the possession rituals and trance states of the Hauka movement in the Gold Coast, present-day Ghana, performed by African workers and migrants who embody and subvert European colonial figures such as Governor, Engineer, and Soldier. Chronicle of a Summer is another ethnographic film that, by contrast, focuses on everyday life in Paris. It relinquishes the authority of a voice-over in favor of polyphonic speech—scattered voices captured in both intimate exchanges and convivial group conversations with factory workers, students, artists, and immigrants. The film’s participatory approach treats the subjects as active collaborators: alongside Rouch and Morin, they conduct interviews with Parisians on themes such as happiness, memory, labor, and alienation. Issues of racism, the French colonial wars, and Holocaust trauma emerge as both topics of discussion and symptoms inscribed in the filmed bodies and environments. This founding film of cinéma vérité explores the limits of participation in cinema, unsettling the boundary between camera and filmed subjects, history and phantasm. At the time, the film had not yet been officially released in cinemas in Paris, so the Saint-Alban screening can be seen as a peculiar avant-première of the film.

Why show these two experimental avant-garde films to the rural population in peripheral southern France? What role could a patient’s or a careworker’s account play in the films’ political or aesthetic impacts? The archives of the production company Argos Films, which sent the film copies to Saint-Alban, preserve a report of the discussion which took place after the screening. The viewers emphasize the unique relation between the camera and lived experience, but also the experimental use of sound.1 Tosquelles offers a psychoanalytic reading of Chronicle of a Summer, highlighting the sexual subtext of certain details—“the bedbug and the drop of blood.” A patient, whose comment concludes the report, admires the use of nonprofessional actors in the film: “You don’t need to be an actor to become a star—it’s within everyone’s reach.”2 Such statements recall the political horizon of those early Soviet films which were programmed by the patients in internal ciné-clubs at the psychiatric clinic. These films rejected theatrical acting in favor of cinema as a tool for constructing and transforming social reality. The Soviet concept of typage—in which actors embodied social types rather than individual heroes—designated both typical representatives of a class and their capacity to act politically in their environment, thus extending cinema into real life.

Grounded in this active relational dynamic between cinema and the real, the 1961 séance with Rouch and Morin—along with the experimental use of media at Saint-Alban—formed part of a collective therapeutic technology: a tool for intervening in the mental and social environments of the clinic. What are the potentialities of the séance as both a cinematic and therapeutic—even psychoanalytic—session? Addressing the theory and the media history of institutional psychotherapy, my essay attempts to trace the implications of this therapeutic form of mediation and its stakes for the present, as a technology of disalienation. By redefining psychosis as both a lived experience of catastrophe—in all its existential acuity—and an attempt at self-repair, institutional psychotherapy conceived of séance as part of its participatory repurposing of technology within a project of disalienation. The broader implications of this understanding of media—and in particular of film as a montage of social and mental ecologies—can be traced in projects that continued and transformed the methods of institutional psychotherapy, such as Frantz Fanon’s practice at Blida-Joinville psychiatric hospital in Algeria or the experiments at La Borde clinic in France, undertaken by Félix Guattari, Jean Oury, Ginette Michaud, and François Pain.3

Lived Experience and the Fantasy of the End of the World

nstitutional psychotherapy emerged in the wake of World War II and the German occupation of France, which led to the ableist mass extermination of psychiatric patients during the severe famine that swept through hospitals.4 At this time, the peripheral hospital of Saint-Alban became an asylum in the literal sense of the word—a refuge not only for patients but also for Jewish migrants, members of the Resistance, and surrealist artists including Georges Canguilhem, Tristan Tzara, Nusch Éluard, and Paul Éluard.5 Engaging with the existing social structures of the region, patients were employed on local farms; activities like sewing, spinning, and knitting for the villagers supplied elements of the barter economy in Lozère. These practices helped the hospital to survive severe scarcity and resist the program of extermination against people with disabilities. After the war, the eugenic and racist conditions of psychiatry were collectively exposed and challenged by the movement of institutional psychotherapy, as schizoanalyst Félix Guattari recalled:

Incapable of supporting concentration camp institutions, [a few nurses and doctors] undertook to transform services from top to bottom, knocking down fences and organizing the fight against famine … Surrealist intellectuals, doctors strongly influenced by Freudianism, and Marxist militants all mingled.6

The historical experience of the war is also inscribed in The Lived Experience of the End of the World in Madness: The Testimony of Gérard de Nerval, Tosquelles’s doctoral dissertation, which he defended in 1948 but which was only published in 1986. In this study, the Catalan psychiatrist took up the challenge of thinking the experience of catastrophe in at least three dimensions: in its clinical expression, in the form of schizophrenia; in its political and historical scope, in the inscription of the war; and in its atmospheric and poetic manifestation, through a concerted analysis of Gérard de Nerval’s novel Aurelia, written shortly before the author’s suicide in 1855.

The book also draws on psychoanalysis’s other—namely, its (dis)engagement with psychosis. Here Tosquelles departs from Sigmund Freud’s account of the case of Daniel Paul Schreber and Jacques Lacan’s early emphasis on the patient’s “lived experience” of psychosis. Better received in artistic and surrealist circles than within the psychiatric or psychoanalytic communities, Lacan’s scathing critique of psychiatry was closely aligned with German existentialism and phenomenology—namely, “to recognize the dynamic primordiality and originality of the lived experience (Erlebnis) in relation to every objectification of an event (Geschehnis).”7 In the surrealist journal Minotaure, Lacan’s essay appeared alongside texts and images by Michel Leiris, Salvador Dalí, André Breton, Pablo Picasso, Marquis de Sade, Paul Éluard, and others. Resonating with these voices, Lacan presents the experience of schizophrenia as a lens through which to study artistic processes:

Now, certain of these forms of lived experience, called morbid, appear to be particularly prolific in modes of symbolic expression, which, as for being irrational in their foundation, are not less furnished with an eminent intentional signification and with a very lofty, tensed [tensionnelle] communicability.8

From this focus on art, Tosquelles extrapolates an “anthropological clinic” to conceptualize a patient’s Erlebnis as the relation between the singularity of an experience and the world it brings about. “What is at stake,” for Tosquelles, “is the dynamic which produces the lived experience [experience vécu] of a person giving it its existential efficacy.”9 Erlebnis etymologically inscribes “life” (Leben) into experience, highlighting the irreducible dimension of the lived temporality of “the end of the world,” and at the same time its complex, paradoxical continuity.

This entangled, nonlinear temporality becomes crucial in Tosquelles’s reading of one of psychoanalysis’s most famous cases: Schreber. The German judge, who developed a highly elaborate psychotic system, used his Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903) as a medium to record and structure his hallucinations, delusions, and experiences of hearing voices. In his own reading of the Memoirs, Freud analyzes Schreber’s mediated “fantasy of the end of the world”—a passage also quoted in Tosquelles’s study at decisive junctures:

At the climax of his illness … Schreber became convinced of the imminence of a great catastrophe, of the end of the world. Voices told him that the work of the past 14,000 years had now come to nothing, and that the earth’s allotted span was only 212 years more; and during the last part of his stay in Flechsig’s clinic he believed that that period had already elapsed. He himself was “the only real man left alive,” and the few human shapes that he still saw—the doctor, the attendants, the other patients—he explained as being “miracled up, cursorily improvised men.” Occasionally the converse current of feeling also made itself apparent: a newspaper was put into his hands in which there was a report of his own death; he himself existed in a second, inferior shape, and in this second shape he one day quietly passed away.10

Schreber experiences the world as scattered in shadows. The meticulous account he provides of this shattered world stems from his systematic attempt to put its dissolution into words. Human shapes, appearing in the repeated rhythmic phrase “miracled up, cursorily improvised” (flüchtig hingemachte Männer), bear witness to a world fleeing its own decomposition. Yet Freud sees in Schreber’s mediation of catastrophe a dialectical phenomenon—one that will also become crucial for Tosquelles: “The delusional formation, which we take to be the pathological product, is in reality an attempt at recovery, a process of reconstruction.”11 In other words, for Freud, the symptom in its performed materiality—the expression of the psychotic phantasm of a deserted world—provides a first step toward (re)structuring this world.

But how can a work of delusion be simultaneously a process of self-repair? According to Tosquelles, psychoanalysis has not gone far enough in this crucial insight. Incapable of grasping the “inherent dynamism” of the psychotic lived experience, it operates with “regression” as “a true catch-all concept in psychopathology” and with mythological explanations.12 Divorced from the clinical fact, it uses primitivist assumptions, which institutional psychotherapy opposes from its very beginnings. Rejecting the psychoanalytic notion of regression and its supposed access to what Freud called the “phylogenetic childhood,” Tosquelles instead turned to a figure who was pivotal for many of his contemporaries, from Georges Canguilhem to Maurice Merleau-Ponty: the German-Jewish neurologist Kurt Goldstein.

Developed in the wake of the catastrophe of World War I, particularly through his collaborative study with Frieda Fromm-Reichmann of war-related brain injuries, Goldstein formulated a far-reaching theory of brain plasticity. According to the neurologist, recovery is never a return to an old state or any preestablished norm, but the organism’s complex and creative effort to reinvent itself in its confrontation with the environment. Far from being a mere deficit, the symptom is, for Goldstein, an “attempted solution”; recovery is “a newly achieved state of ordered functioning”—a “new individual norm.”13 In accounting for the crisis brought about by the symptom—emotional confusion, anxiety, or despair arising from an individual’s inability to adapt immediately to a situation following neurological injury—Goldstein speaks of “catastrophic reactions.” He analyzes these as “inevitable way stations” in the process of self-actualization—expressions, moreover, of the individual’s “inescapable participation in the general imperfections of the living world.”14

Tosquelles adapts Goldstein’s entangled relation between the negativity of the symptom and the body’s creative potential for self-repair. He affirms that “annihilation of the self and the world” is not in itself a negative fact but a “crucial moment in the dialectical evolution of the organism.”15 Yet for Tosquelles, the human milieu is not merely biological—it is also irreducibly social. Thus, the catastrophic reaction is experienced not only somatically but relationally, as a “modification of the meaning of our ties to others.”16 Thus Tosquelles recognizes the value of pathology in the ability to deviate from and reinvent given norms—an affirmation radically opposed to the ableism and eugenics of his time. The effort to repair a shattered world opens up the possibility of creative (re)singularization and (re)socialization. Psychosis, then, is not a passive condition or a biological deficit, but an expression of an affirmative potential imbued with both “freedom” and a “sense of responsibility.”17 In his sociogenic approach, Fanon—who spent fifteen months working closely with Tosquelles at Saint-Alban—expanded the idea of the symptom as embedded in its social and political environment.

Disalienation and Transference

Crucially, for Tosquelles, institutional psychotherapy could not efface catastrophe—whether mental or geopolitical—but might instead configure resistance and repair from within the catastrophic horizons of history and its ruinations. Therefore, it refused to limit itself to individual bodies and their symptoms, but instead turned to the social, mental, and environmental conditions in which these symptoms had evolved. From this perspective, “madness” was considered as a “disorder in the relationship between the self and the world.” To be out of one’s mind—aliéné—in French already carries the weight of estrangement.

Institutional psychotherapy theorized madness as a double estrangement: both mental and social alienation of the self from its “participation in the environment.”18 Undertaking a Marxist rereading of psychoanalysis, the movement operated via group therapies and a radical restructuring of psychiatric institutions, involving patients in their capacity to actively participate in each other’s healing processes. Instead of an individual treatment, the disalienationist approach proposed to “cure the ‘surrounding’ and the ‘hospital.’” Drawing attention to the fact that the “hospital is ill,” the movement aimed at collectively transforming its “environment” and “atmosphere.”19 Experimental use of media, such as film, printing workshops, cartography, and audio recording, were crucial in the formation of such therapeutic environments. These media served to reinvent the geography of the given relations: to produce environments, institutions, and milieus that would facilitate psychological therapy and healing.

The séance featuring films by Rouch and Morin was part of this mediated strategy of disalienation. This is further underscored by the fact that, at the time of the double screening, a trilogy of cinéma vérité films was being produced in Lozère by the Italian-French filmmaker Mario Ruspoli, in close collaboration with Tosquelles. Ruspoli’s cameramen, Roger Morillière and Michel Brault, were founding figures of cinéma vérité and direct cinema. Both collaborated on Chronicle of a Summer, transforming studio-based documentary norms through handheld camera techniques that were attuned to the spontaneous rhythms of speech, gestures, and settings.

Two of their films made in Lozère were dedicated to the life of Saint-Alban clinic: A Look at Madness (1962) and Captive Feast (1962).20 Both films avoid voice-over explanation or clinical discourse, creating instead an atmosphere of attention and presence in the complex milieu marked by institutional transformations. The camera reveals the rhythms of life inside the institution—the textures of bodies, materials, and the spaces of care—as therapeutic agents in the project of disalienation. In this sense, both films emerged as acts of participation in the lived experience of the hospital. And even more so, according to Tosquelles, they “venture to make you truly participate in the lives of these human beings [participer dans la vérité à la vie]—in their anxieties, their hopes, and their struggle to reconnect with reality, with the social world, with everyday life—a struggle shared by doctors and patients alike.”21

Participation, in the form of such cinematic experience—“expérience” in French meaning both “scientific experiment” and “lived experience”—was central to the socially situated project of disalienation. In the first place it was a mediated redefinition of the psychoanalytic notion of transference (Übertragung) towards a collective and milieu-generative dimension. In the second place, as I would like to suggest, this form of participation—reconfigured as a cinematic and collective mediation of transference—also shaped the methods and aesthetic language of cinéma vérité.

Saint-Alban’s technologies of disalienation must be understood as grounded in a mediated and praxeological redefinition of the psychoanalytic notion of transference. Freud understood transference as a unique relational dynamic during treatment, i.e., between the analyst and their patient, in which “infantile prototypes re-emerge and are experienced with a strong sensation of immediacy.”22 Institutional psychotherapy radically decentered and unsettled this relation. It explored the material and institutional infrastructures of psychotherapy, as well as the patients’ capacity to play an active role in one another’s healing processes as elements of a complex “transferential constellation.” Thus, transference was no longer conceived as a binary patient-doctor relation, but as a set of multiple, horizontal vectors encompassing the social and environmental extensions of the institution. As psychiatrist Pierre Delion emphasized, “It was about accounting for the specificity of psychosis and reestablishing a metapsychology of transference according to its measure.”23 At the same time, for Tosquelles, this implied an ethical stance: a deprofessionalization of the healthcare worker. Considering the communal situation of the clinic—as opposed to the psychoanalytic setting of an interpersonal cure—he wrote: “Psychotherapy was truly the work of everyone, not just the psychoanalysts.”24

This redefined model of psychoanalysis in turn crucially exceeded the notion of the unconscious as based on language. It accounted for bodily movements and gestures as agents of tranferential constellations, also theorized by Jean Oury, the founder of La Borde clinic. Tosquelles spoke of scattered transference (transfert éparpillié), which implied that transferential investments can also be deployed on objects and spaces.25 The fundamental awareness of the spatial and aesthetic dimensions in therapy opened institutional psychotherapy to cinematic processuality and mediation, with its valorization of the perceptual field and its structuring forces. Broadening the psychoanalytic vocabulary, institutional psychotherapy proposed an analysis of situème as a spatial equivalent of phonème in order to account for the complexity of a transferential situation: of situated bodies and gestures, velocities and sounds that play an essential role in social environments.

Guattari later took this idea of the spatial heterogenesis of relations and adapted it for his notion of transversality, initially coined by Ginette Michaud. Based on the collective media experiments at La Borde, Guattari assumed that film could help grasp the pragmatic of unconscious investments in the social field.26 In his audacious text against structuralist and bourgeois psychoanalysis, “The Poor Man’s Couch,” Guattari explores cinema as a privileged place for such investments. Attuned to the mediated model of transference proposed by institutional experiments, he states that

the unconscious does not manifest itself in cinema in the same way it does on the couch: it partially escapes the dictatorship of the signifier, it is not reducible to a fact of language, it no longer respects, as the psychoanalytical transfer continued to do, the classic locutor-auditor dichotomy of meaningful communication.27

In this respect, cinema not only helps to undo any transcendent subject of enunciation, but opens up a fragmented—or montaged—array of “asignifying semiotic chains of intensities, movements, and multiplicities.”28 Guattari is not blind to the alienating powers of commercial mass cinema; however, he recognizes its machinic capacity to intervene directly in our relations with the external world. This form of participation in the heterogeneous manifestations of experience gives rise to a cinematic unconscious—one “more precarious,” yet full of promise for disalienation.29

The media histories of institutional psychotherapy invite us to reconsider the séance as both a psychoanalytic and cinematic technology of disalienation. These minor experiments with media are reflected in the history of cinéma vérité, even beyond the séance with Rouch and Morin in 1961. Between 1950 and 1957 Tosquelles, together with his wife Elena Alvarez Tosquelles and the patients of Saint-Alban, produced a film titled Lozerien Society of Mental Hygiene. Made with an 8 mm Paillard camera, the film was meant to be seen with the patients of Saint-Alban and circulated in the confines of other institutions in three parts: “Social Therapy,” “Ergo-therapy,” and “Parties” (fêtes). It presents the clinic as a “society,” a formation of resistance against the given conditions of confinement.

Despite its poor means, the film finds strong resonances in Ruspoli’s Captive Feast, which is dedicated to the annual Fête Votive at Saint-Alban. Both films feature carnival celebrations, organized around the region’s patron saint. Both avoid representation in favor of participating in and mediating the complex temporality of this event. The objects and bodies recorded by the camera form part of the therapeutic environment of Saint-Alban: the costumes and masks crafted by patients during ergo-therapy sessions, and the theatrical and musical performances rehearsed in social therapy ateliers. Both films depict the environmental and social opening of the clinic—an opening theorized by the movement as “geo-psychiatry”—where local inhabitants of Lozère join to celebrate with the patients. This social transversality dismantles the binary between the “normal” and the “pathological,” favoring instead the coexistence of singularities, as explored by Goldstein and Canguilhem.

Finally, I would like to suggest that a form of transference occurs between these two films—one that connects the gestures and movements of the carnivalesque collectives not only with one another, or with the act of capturing them on film, but also with the transmission of these experiences into an open-ended temporality of the future, in which new technologies of disalienation might emerge.

-

See the detailed analysis of this Lozerien screening in Séverine Graff, Le cinéma-vérité: Films et controverses (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2014), 171–73. ↩

-

Graff, Le cinéma-vérité, 172. ↩

-

Regarding La Borde, see also the recent solo exhibition of Pain, François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles (February 21 through May 17, 2025), curated by Perwana Nazif; and Everybody Wants to Be a Fascist: Institutional Psychotherapy as a Resistance Movement by François Pain, ed. Perwana Nazif (Semiotext(e), 2025). ↩

-

Max Lafont, L’extermination douce: La cause des fous, 40000 malades mentaux morts de faim dans les hôpitaux de Vichy (Éditions du Bord de l’eau, 2000). ↩

-

See also Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry, Radical Politics, and Art, ed. Carles Guerra et al. (American Folk Art Museum, 2024). ↩

-

Félix Guattari, Psychoanalysis and Transversality: Texts and Interviews 1955–1971, trans. Ames Hodges (Semiotext(e), 2015), 60. ↩

-

Jacques Lacan, “The Problem of Style and the Psychiatric Conception of Paranoiac Forms of Experience,” Critical Texts: A Review of Theory and Criticism 5, no. 3 (1988): 4. ↩

-

Lacan, “The Problem of Style.” ↩

-

François Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin du monde dans la folie: Le témoignage de Gérard de Nerval (Jérôme Millon, 2012), 51. ↩

-

Sigmund Freud, “The Case of Schreber,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, vol. 12 (1911–13) (Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1964), 68. ↩

-

Ibid., 71. ↩

-

Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin, 92. ↩

-

Kurt Goldstein, The Organism (Zone Books, 1995), 334. Goldstein’s book contains a very insightful critique of the Freudian theory of culture: “But in no way could one claim that this ‘ordered’ world, which culture represents, is the product of anxiety, the result of the desire to avoid anxiety, as Freud conceives culture as sublimation of the repressed drives. This would mean a complete misapprehension of the creative trend of human nature and at the same time would leave completely unintelligible why the world was formed in these specific patterns … This tendency toward actualization is primal; but it can effect itself only in conflicting with, and in struggling against, the opposing forces of the environment. This never happens without shock and anxiety” (239). ↩

-

Goldstein, The Organism, 392. See also Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers, The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe: Brittleness, Integration, Science, and the Great War (University of Chicago Press, 2018). ↩

-

Tosquelles, Le vécu, 95. See also Mateo Pasquinelli and Elena Vogman, “Catastrophe and Schizophrenia: Curing the Institution in a War Shattered World,” in Fragments of Repair, ed. Kader Attia, Maria Hlavajova, and Wietske Maas (Jap Sam Books, 2025). ↩

-

Tosquelles, Le vécu de la fin, 95. ↩

-

Ibid., 98. ↩

-

Lucien Bonnafé et al., “Valeur de la théorie de la forme en Psychiatrie: La dialectique du Moi et du Monde et l’événement morbide,” Annales Médico-Psychologique 103, no. 2 (1945): 280. See also Camille Robcis, Disalienation: Politics, Philosophy, and Radical Psychiatry in Postwar France (University of Chicago Press, 2021). ↩

-

François Tosquelles, Le travail thérapeutique à l’hôpital psychiatrique (Éditions du Scarabée, 1967), 40. Jean Oury, “The Hospital Is Ill,” interview by Mauricio Novello and David Reggio, Radical Philosophy, no. 143 (May–June 2007): 35. ↩

-

See Mireille Berton, “Regard sur la folie: poétique et politique de la folie et du cinéma,” Décadrages, no. 18 (2011); and Perwana Nazif, “Filming in and of the Asylum: French Radical Psychiatry on Screen,” Notebook, MUBI, July 2024. ↩

-

François Toquelles, “Regards sur la folie,” 1961. I want to thank Jacques Tosquellas for sharing with me this yet-unpublished text. ↩

-

Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis, The Language of Psychoanalysis (Karnac Books, 1988), 455. ↩

-

Pierre Delion, La constellation transférentielle (Éditions érès, 2022), 23. ↩

-

François Tosquelles, “Les retrouvailles: Sèvres (1957–58),” Recherches: Histoire de la psychiatrie de secteur ou le secteur impossible?, no. 17 (1975): 176. ↩

-

My thanks to Tosquelles scholar and curator Joana Masó for highlighting this notion. ↩

-

Félix Guattari, “The Poor Man’s Couch,” in Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972–1977, ed. Sylvère Lotringer (Semiotext(e), 1995), 262. ↩

-

Guattari, “Poor Man’s Couch,” 262–7. ↩

-

Guattari, “Poor Man’s Couch,” 262–7. ↩

-

Guattari, “Poor Man’s Couch,” 262–7. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776768/s-ance-technology-of-disalienation

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.