Summoning the Beings of Metamorphosis

Namsee Kim

Namsee Kim studied aesthetics in Seoul and cultural studies in Berlin. Since 2015, he has been a professor of Studies in Visual Arts at the College of Art & Design, Ewha Womans University. He is the author of Art, Madness, and Writing (2016) and What is Seeing (2013), and has translated several works into Korean, including Daniel Paul Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (2010), Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (2019), and Boris Groys’s On the New (2017). He explores and researches contemporary philosophies and art theories, while writing critiques of artists working in diverse fields such as painting, installation, media art, sound art, and performance.

Research Title Summoning the Beings of Metamorphosis

Category Essay

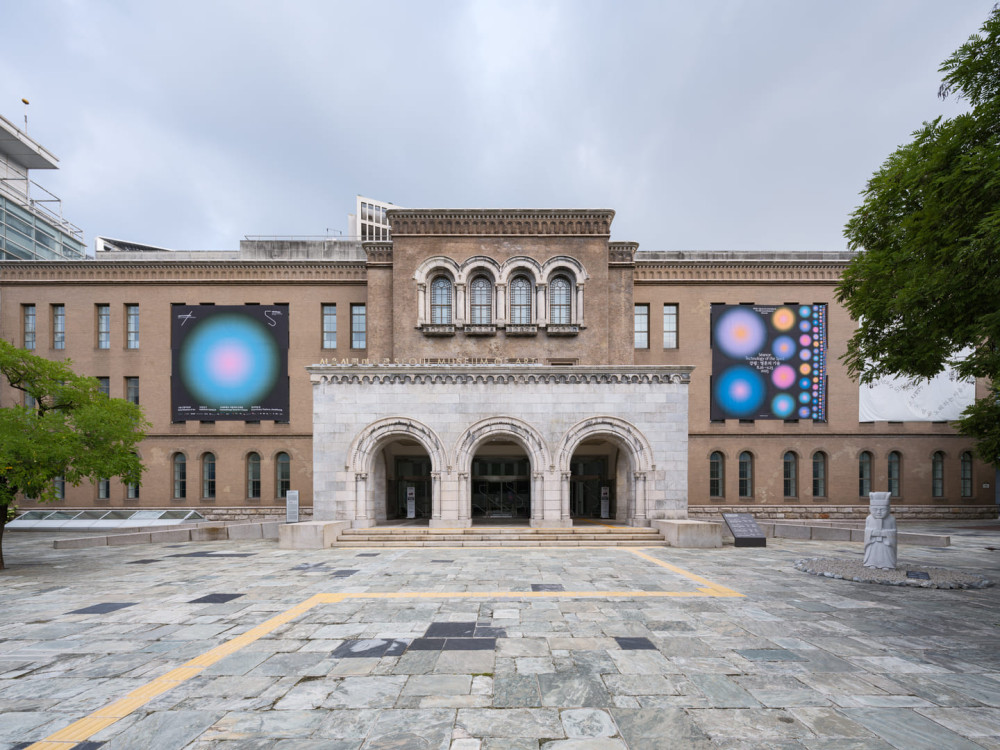

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Namsee Kim

Once freed from Bifurcation, nothing will keep you from reconnecting with existents with which you have in fact never ceased to interact.

—Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence1

The modernist project was characterized by the dismissal of all other epistemologies and cosmologies as not only primitive but unreal. Its advocates, wrote Bruno Latour, “make condescending fun of the ‘other tribes’ or the ‘bumpkins’ who are ‘still’ obliged to believe in sorcery, to protect themselves with fetishes or amulets, to send for a spell-breaker, or to go through a shaman to interpret their dreams.” These advocates classify as superstition “the enormous work done by the COLLECTIVES known as ‘traditional’ to capture, situate, institute, and ritualize ‘invisible beings.’” The modernist process asserted that these invisible beings “are only internal representations projected onto a world that is in itself devoid of meaning,” stripping them of all “external existence.” Latour aims to grant them “externality, their own truth.”2 This is no easy task.

One way of carrying out this task is to attend to what these “invisible beings” have done for us. In the traditional Korean context, as elsewhere, they have helped us understand the otherwise inexplicable ill luck that individuals encounter, as well as the desires and frustrations that arise from various situations and conditions. They have led us to believe that there is a cosmic order that transcends humanity, and with which we must live in harmony if we are to live safely. They comfort the unfortunate and vulnerable, prompt reflection on how present misfortune connects to the past, remind us of our relationships with the deceased, and help us realize that a person’s death does not signify the end of everything.

These difficult beings desire, feel jealousy, and take offense when they believe they’ve been mistreated, tormenting the living in return. However, when offered a feast and pleasant words, they are appeased and watch over humans. In Korean society, these beings have played an important role in enabling women to assume key places “across the boundaries of patrilineal kinship” and to establish “cooperation across generations of potentially antagonistic in-marrying women.”3 Latour refers to these beings who interact with us in this way, altering both us and themselves into something else, as “beings of metamorphosis.”

“We have to pass through artificial arrangements, rituals,” writes Latour, if we are to become “familiar” with these beings of metamorphosis.4 They emerge in the interstice between rituals and their objects, connecting with us through them. The bells shaken by shamans summon them; they linger on spirit tablets, the clothing of the deceased, and bundles of pine needles hung from roof beams. They announce their arrival through the trembling of pine branches, the fluttering of five-colored divination flags held by the possessed, or the sliding of the planchette beneath the hands of those who call them forth.

The anthropologist Laurel Kendall challenges the view that certain ritual items—such as wall images and paper flowers dedicated to house guardian gods; kitchenware like brown pottery, jars, and rice winnowers believed to house the souls of ancestors and the dead; as well as candlesticks, incense burners, fans, mirrors, knives, and other tools used by shamans—are “animate” fetishes. She argues instead that “gods, souls, and more generalized spirits make use of different kinds of material things and they do so in different ways.”5 This is not, she argues, an animist worldview in which inert objects are invested with particular spirits but rather evidence of the mobility of spirit, such that it can move into otherwise inanimate things and, indeed, into the bodies of shamans. It is a combination of human agency and spirit intention that causes gods to be present in jars or baskets and paintings, and which may also cause them to depart these vessels.

Therefore, before judging someone who is flinging their arms and talking loudly to themselves as strange or abnormal, we should ask ourselves, as Latour asks, “who is being addressed … and what apparatus serves as their go-between?”6

The Magic Mountain

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924) opens with a young engineer, Hans Castorp, visiting his cousin Joachim, who is hospitalized for tuberculosis at a sanatorium in the Alps. During the seven years he spends there after himself being diagnosed with tuberculosis, the protagonist has a “highly questionable”7 experience with a séance. A nineteen-year-old Danish girl named Ellen Brand demonstrates extraordinary abilities during a social hour spent playing parlor games—where players search for hidden objects or guess tasks assigned by others. It turns out that a spirit named Holger had been helping her for a long time. Upon learning of this, the sanatorium residents organize a “spiritualistic parlor game” with her as the medium, and Castorp takes part in one of the sessions. The room is equipped with

a bare, round, medium-size table in the middle of the room; a wine glass placed upside down on it; and around the edge of the table, at regular intervals, little ivory squares, tokens from some game or other, on which twenty-five letters of the alphabet had been drawn in ink … Once they had all warmed themselves [with tea], they sat down at the table, and by dim pinkish light—to enhance the mood, their hostess had extinguished the ceiling light and left only the red-shaded nightstand lamp burning—each of them placed one finger of his or her right hand gently on the upturned base of the glass. This was standard procedure. They waited for the glass to set itself in motion.8

Here, the upside-down wine glass is used in place of the usual wooden planchette, which participants guide with their fingers during the séance, and letters of the alphabet are placed around the table. The engineer Castorp doubts the credibility of the séance. A wine glass on a smooth table requires only the slightest nudge to move, so with uneven finger pressure it could easily glide one way and bump into specific letters. Should these letters happen to form intelligible words, the participants will naturally interpret it as the soul of the dead speaking through the glass. But isn’t this giving form to the expectations people have placed on these “pseudo- or semi-realities that are called magical”? And if so, isn’t it ultimately just “a very complex phenomenon, almost impure in its intricacy, a blend of conscious, half-conscious, and subconscious elements … of each person”?9

Then, surprisingly, the summoned spirit arrives amidst the table, the glass, and the people with their fingers on it. The spirit reveals its name and former occupation as a poet, and even composes a persuasive poem about the ocean and time. When Holger’s spirit moves the wine glass, “bold and dreamy phrases of things” flow out. Who is the agent of this “magical bit of reality” in which “dreamily self-revealing” sentences and poetry emerge? Ellen Brand the medium? Her guardian angel, Holger? The participants who moved their hands and bodies with the upside-down wine glass? Or a network of human and nonhuman beings, composed of a table, a wine glass, twenty-five letters of the alphabet, and the spirit that came to exist there?

After this incident, the modern bifurcation that had dominated Castorp’s world begins to crumble, and his once-firm distinctions between material and immaterial, reality and dreams start to blur. When the rationalist Herr Settembrini asserts that séances are nothing but trickery and Ellen Brand a despicable fraud, Castorp “did not say yes or no” but rather

shrugged and observed that since reality could not be determined beyond the shadow of a doubt, neither, then, could fraud. Perhaps the boundaries were fluid. Perhaps there were transitional stages between the two, degrees of reality within nature, which, being mute, could not be evaluated and thus eluded a determination that, as he saw it, had something very moralistic about it. What did Settembrini think of the term “illusion”—a state in which elements of dream and reality were blended in a way that was perhaps less foreign to nature than to our crude everyday thoughts? The secret of life was literally bottomless, and it was no wonder, then, that occasionally there rose up out of it illusions.10

The phrase “secret of life” echoes Henri Bergson’s concept of “élan vital” as the driving force behind organic evolution. In his 1912 lecture “Soul and Body,” Bergson emphasizes that the mind/soul is independent of the body. Just as our perceptions and memories surpass the body, which is bound by time and space, mental life does not result from bodily functions. Rather, it is the body that is used by the mind. It is plausible to believe that mental life continues after the death of the body because “the only reason we can have for believing in the extinction of consciousness at death is that we see the body become disorganized.” 11 He developed this argument at the Society for Psychical Research in 1913, arguing that the “mental life [is] much more vast than the cerebral life” and so “the burden of proof comes to lie on him who denies [the survival of the mind after the death of the body] rather than on him who affirms it.”12

Dr. Krokowski, one of the doctors in The Magic Mountain, represents early twentieth-century psychiatry, which was closely intertwined with occultism. Like psychiatrists of the time such as Pierre Janet and Théodore Flournoy, he conducts experiments with a medium using scientific methods and devices.13 In his words, the phenomena that arise during this “training”—such as a wastebasket floating, the pendulum of a wall clock held back and then set in motion again, and a serving bell ringing—arise from the capacity of thoughts “to assume substance and thus reveal themselves in ephemeral reality,” as a consequence of “biopsychic projections of subconscious complexes into the objective world.” He also emphasizes that the dim lighting in the laboratory he had prepared for sessions was not for “mystification” but to “set the mood.” His experiment turns out to be quite successful: a young man’s handprint appears on a flour-dusted plate, a participant is given a “hefty slap on the cheek from the transcendent world,” and some even “held such a ghostly hand.”14 However, the most dramatic experiment is the summoning of the spirit of Castorp’s deceased cousin, Joachim Ziemssen.

The Fantastic

What exactly is the spirit of Joachim in military uniform that appears before Castorp’s eyes? Is it a collective hallucination created by the dim lights and intense emotions of the participants, or even someone’s trickery? If so, The Magic Mountain would meet Tzvetan Todorov’s definition of the uncanny.

In The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre (1975), the literary critic defines “the fantastic” as the tension between “the uncanny” and “the marvelous.” The distinction between the two is determined by how a narrative treats supernatural phenomena—events that transcend the laws of reality—within a given work. When the events are initially incomprehensible, inexplicable, and seemingly supernatural, but are ultimately revealed to be the protagonist’s dreams or hallucinations, or the trick of an intelligent criminal (as in detective stories), such works fall under the category of “the uncanny.” In that case, the reader finds “that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described.”15

On the contrary, when elements such as flying carpets or dragons appear, and the reader decides that the phenomena require new laws of nature to be explained, then the work falls into the category of “the marvelous.” “The fantastic” occupies the boundary between the two, forcing the reader “to hesitate … between a natural and a supernatural explanation.”16 When it is impossible to decide whether the laws of reality hold or whether new natural laws must be assumed, the hesitation that arises in the absence of complete disbelief or absolute faith is the condition of “the fantastic.”

The Magic Mountain neither denies nor explains the appearance of Joachim’s spirit during the séance, opening up a realm of the fantastic for readers. Something here frightens us, but we cannot decide whether we are “anxious whereas there is actually nothing outside; or, on the contrary, not to realize that, if one is frightened, it is because there really is something that provoked the fright, something pressing.”17 With this hesitation we enter the realm of “the fantastic,” and there the beings of metamorphosis, these “peculiar aliens,” appear: “‘I thought it was nothing, but then I turned around and there it was, terrifying’; or, conversely, ‘I thought it was something, but then I turned around and there was nothing there after all.’”18

Surrealism

Thomas Mann set these peculiar external entities within a remote sanatorium in the Alps, separate from the “real” world inhabited by the author and his readers. In contrast, surrealism attempts to find these outsiders in the here and now, not only close to but within us.

On the night of September 25, 1922, André Breton and his wife Simone Kahn gathered with young poets René Crevel, Max Morise, and Robert Desnos for a séance. Their séance was not about summoning the souls of the dead but rather about summoning the others within their minds. Soon after they sat around a table holding hands under dim lighting, they one by one began to utter words or sentences in a trancelike state. This marked the beginning of the “sleep sessions” that continued through to the spring of 1923, with the participation of Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, Max Ernst, Louis Aragon, Man Ray, and Giorgio de Chirico. Crevel, Desnos, and Péret repeatedly fell into a trancelike state, speaking, answering questions, writing on paper, or drawing. As it became increasingly difficult to awaken Desnos from this state, and some of the participants even attempted suicide, Breton terminated the sessions.19

The words and sentences uttered in a trance state amazed them. Not only were they poetically brilliant, but they also seemed to have the power to predict future events.20 In Nadja (1928), Breton compares them to an “oracle.”

I see Robert Desnos at the period those of us who knew him call the “Nap Period.” He “dozes” but he writes, he talks … Desnos continues seeing what I do not see, what I see only after he shows it to me … Those who have not seen his pencil set on paper—without the slightest hesitation and with an astonishing speed—those amazing poetic equations, and have not ascertained, as I have, that they could not have been prepared a long time before, even if they are capable of appreciating their technical perfection and of judging their wonderful loftiness, cannot conceive of everything involved in their creation at the time, of the absolutely oracular value they assumed.21

Interestingly, this artificial somnambulism of “writing and speaking while dozing” was no different from the mindset required of participants in séances to summon the souls of the dead. Dr. Krokowski told the séances participants sitting hand-in-hand around the table not to concentrate; there should be “no strenuous concentration or forced visualization of their anticipated visitor—the only thing that helped was a casual, floating attentiveness.”22 The “loosening of the self by rapture” necessary for summoning the souls of the dead is equally essential for summoning the other within the mind.23 The 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism includes the following definition:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.24

The objective of this method is to recreate the scene we witnessed at the Alpine sanatorium: wine glasses moving across the table and “dreamily self-revealing” words and verses emerging. The cover of the first issue of La Révolution Surréaliste, published in the same year as The Magic Mountain, featured a photograph showing a small, bare table in the middle of a room, on which there is a paper-loaded typewriter. Sitting in front of it is Simone Kahn, holding a pair of opera glasses in her right hand, as she looks at Robert Desnos, who is acting the role of a medium. As suggested by the photograph’s title, Waking Dream Séance, when the awake Desnos utters his dream, Kahn’s fingers will strike the typewriter keys, spelling it out letter by letter onto the paper.

-

Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns, trans. Catherine Porter (Harvard University Press, 2013), 205. ↩

-

Latour, Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 183–201. ↩

-

Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Housewives, and Other Restless Spirits: Women in Korean Ritual Life (University of Hawai‘i Press, 1985), 127, 169. ↩

-

Latour, Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 194. ↩

-

Laurel Kendall, “Gods and Things: Is ‘Animism’ an Operable Concept in Korea?” Religions 12(4), no. 283 (2021): 13. ↩

-

Latour, Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 189. ↩

-

This is the title of the seventh chapter of The Magic Mountain, in which this episode appears. Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, trans. John E. Woods (Alfred A. Knopf, 1995). ↩

-

Mann, Magic Mountain, 650–51. ↩

-

This and following quotes from the same passage are taken from Mann, Magic Mountain, 651–54. ↩

-

Mann, Magic Mountain, 657. ↩

-

Henri Bergson, Mind-Energy: Lectures and Essays, trans. H. Wildon Carr (Henry Holt and Company, 1920), 73. ↩

-

Bergson, Mind-Energy, 97–98. ↩

-

The Swiss psychiatrist Théodore Flournoy, believed to be the model for Krokowski, published his research with the medium Helene Smith (the pseudonym of Catherine-Elise Muller) in the 1900 book From India to Planet Mars. Tessel M. Bauduin, Surrealism and the Occult: Occultism and Western Esotericism in the Work and Movement of André Breton (Amsterdam University Press, 2014), 42. ↩

-

All quotes in this paragraph taken from Mann, Magic Mountain, 706–12. ↩

-

Tzvetan Todorov, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, trans. Richard Howard (Cornell University Press, 1975), 41. ↩

-

Todorov, The Fantastic, 33. ↩

-

Latour, Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 186. ↩

-

Latour, Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 202. ↩

-

Bauduin, Surrealism and the Occult, 35–36. ↩

-

“Another fateful encounter occurred on the night of May 29, 1934. Breton met an unknown woman with hair like ‘bright rain on a flowering chestnut tree.’ They took a long night stroll through the narrow alleys of Les Halles. A few days later, Breton realized that the circumstances of this encounter appeared in his poem of automatic writing, ‘The Night of the Sunflower,’ written on August 26, 1923. After closely examining each of the 31 lines of ‘The Night of the Sunflower,’ Breton concluded that the entire poem from 1923 was ‘foretelling that something very significant would happen to me in 1934.’” Georges Sebbag, Le surréalisme, trans. Choi Jeong-a (Dongmunseon, 2005), 91. ↩

-

André Breton, Nadja, trans. Richard Howard (Grove Press, 1960), 31–32. ↩

-

Mann, Magic Mountain, 664–67. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, “Der Surrealismus: Die letzte Momentaufnahme der europäischen Intelligenz” (1929), in Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften, vol. II-1, ed. Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser (Suhrkamp, 1977), 297. ↩

-

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (University of Michigan Press, 1969), 26. ↩

The English version of this essay is also availalbe in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776773/summoning-the-beings-of-metamorphosis

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.