Traces of Cosmos: Notes on Hilma af Klint’s Paintings and their Reception

Maria Lind

Maria Lind is a curator, writer, and educator based in Stockholm and Kiruna. Since 2023, she has been the director of the Kin Museum of Contemporary Art in Kiruna. From 2020 to 2023 she served as the counsellor of culture at the embassy of Sweden in Moscow. She was the director of Stockholm’s Tensta konsthall (2011–2018), the artistic director of the 11th Gwangju Biennale, the director of the graduate program, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College (2008–2010), and director of Iaspis in Stockholm (2005–2007). She has taught widely since the early 1990s, including as a professor of artistic research at the Art Academy in Oslo (2015–2018), and as a lecturer at Konstfack’s CuratorLab.

Research Title Traces of Cosmos: Notes on Hilma af Klint’s Paintings and their Reception

Category Essay

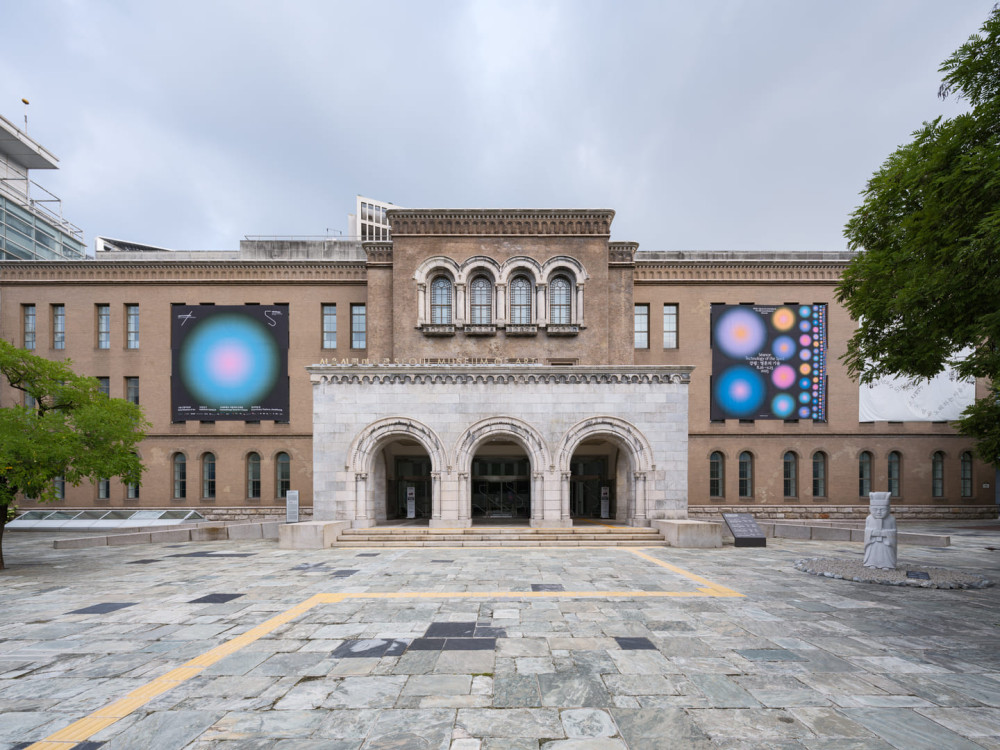

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Maria Lind

The abstract and occult images for which Hilma af Klint is now famous came to her in visions, and she herself never fully understood what they meant. At first, it was only a small group of close female friends and collaborators who were allowed to see them, then enthusiasts who shared her Rosicrucian, Theosophist, and Anthroposophist beliefs, plus a young naval officer who happened to be her nephew. The founder of the Anthroposophical Society, Rudolf Steiner, was one of the lucky few to be allowed firsthand experience of the paintings; he said it would take half a century for them to be understood.

As it turned out, it took a bit longer, if we can claim even today to be beginning to “understand” them. Having stated that her abstract works should not be made public until twenty years after her death, which occurred in 1944, Hilma af Klint’s sole inheritor, the aforementioned naval officer, took it upon himself to save the work. In 1972, he established the Hilma af Klint Foundation, which holds almost the entire oeuvre of the artist and has until recently respected her will and the principles that she laid out. Subsequently, thanks to the art historian Åke Fant, who was himself affiliated with the Theosophists and who taught at the University of Stockholm, her work was researched, published, and shown in several exhibitions in the 1980s.

The most prominent of these was “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985,” an ambitious survey of the esoteric side of the avant-garde at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986. Af Klint’s work was a sensation: an obscure female artist from Stockholm with an extensive oeuvre of abstract paintings shown next to Vassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian. Three years later, “Secret Pictures by Hilma af Klint” opened in Helsinki before traveling to Reykjavik, Olso, Bergen, Odense, and New York, where 117 works were displayed at MoMA PS1. Shortly afterwards an extensive monograph was published and Stockholm’s Moderna Museet organized a retrospective which found its way to Gothenburg, Lund, and Odense. Yet another exhibition toured Vienna, Graz, and Passau.

The pattern continued into the early 2000s, notably with an exhibition of af Klint, Emma Kunz, and Agnes Martin at the Drawing Center in New York. In 2005 there was a second solo exhibition at Moderna Museet and then, in 2006, yet another solo at London’s Camden Art Centre. All of this is impossible to square with the assertion of af Klint’s biographer Julia Voss that Moderna Museet “discovered” af Klint in 2013. (This was the museum’s third major exhibition of her work.) Nor does it fit the narrative that af Klint was somehow unknown to the public until the Guggenheim in New York put on a blockbuster retrospective in 2019. What would the artist—who spent her life seeking out those who could help her decode the work rather than the affirmation of the institutional art world—have made of all this?

But first, back to the pictures themselves. Af Klint left behind more than 1,300 paintings, made in spurts spanning a few months to several years over the course of nearly four decades. Some of these canvases are larger than any known abstract paintings made before the end of World War II. Trained as an academic painter with naturalistic leanings at the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm, and versed in spiritualist practices, she came to be led by voices and visions, learning that she should work in the service of “the mysteries.” Many of the pictures were made under the guidance of spiritual leaders with names like Gidro and Amaliel, Gregor and Ananda. These higher powers directing her hand, her “commissioners,” were from Tibet, she claimed, and their messages were eternal. Hers was a transcendental experience, often preceded and accompanied by fasting and praying, and supported by her deep belief in invisible realities and a continuum between matter and spirit.

Af Klint considered herself, in other words, an instrument. This is in contrast to artists such as Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian, whose more individual, intellectual, and analytical approach to abstraction developed more gradually, at least according to teleological art histories. Even if all four of them shared an interest in the occult tendencies of their time, these men saw themselves as proponents of a new type of art led by formal experiment, in sync with the historical moment, and developed in dialogue with artists in the context of a public sphere including galleries, museums, and publications. Painting, to af Klint, was a revelatory practice. She worked in almost total isolation, only twice exhibiting a handful of her spiritual works publicly, and only then in the context of Theosophical and Anthroposophical conferences. None of them were reviewed, and this part of her practice remained a secret to the world beyond her small group of confidants.

According to af Klint, her paintings depict the imperishable (today, it is easy to call them visionary). They convey a vibrant, complex, and syncretic cosmos in which different religions intermingle, although Christianity is the basis, and natural science plays a role. She created an elaborate system of symbols, returning again and again to her own version of the Platonic idea of an original androgynous creature who, after being split in two, spends its life seeking the other half. The incomplete halves of man and woman, masculine and feminine, are examples of the necessary reunion of opposites and the need to overcome dualities. There are plenty of snails in her paintings: they are hermaphrodites, literally overcoming the split. Among her telling titles are Primordial Chaos, The Ten Greatest, The Atom, Parcifal, Mahatma’s Present Standpoint, Contemplating the Rosehip, and The Kidneys (Female).

Eldslågor (Fiery Flames, 1930), the work presented in the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, belongs to a late series of small-scale drawings and watercolors made when arthrosis had made painting at a large scale difficult for the artist. At this point, the assignment from the spirits had been completed, the lines from the earlier works had dissolved, and the abstract shapes had become blurry. It was now more Turner and Monet than Malevich and Mondrian. The painting shows a fluidly painted yellow hill with violet and orange flames on top, and what appears to be a sun in the top right-hand corner. A bluish-violet heart with yellow flames coming out of the top is placed inside the hill, almost at the bottom. Reminiscent of the motif of the Sacred Heart in Christian iconography, symbolizing devotion to Christ’s sacred humanity and God’s boundless love for mankind, the heart is here embedded in the earth, indicating the sacredness of the planet. The airy painting once belonged to Elsa and Magda Jerud, two sisters who trained as textile artists and kept a studio out of which they sold their work in the south of Sweden. Af Klint befriended them through the Anthroposophical Society and gifted them the picture. It was sold at an auction in 1988, after their deaths, making it one of few privately owned occult works by af Klint.

Among spiritualist artists like Emma Kunz, Georgiana Houghton, and Agnes Pelton, af Klint’s oeuvre stands out for its oscillation between purely geometric and abstract forms of representation and fully naturalistic figuration, even scientific illustration, as Eldslågor demonstrates. For instance, she made studies of grains and other plants as well as their abstract, “astral” ideals. From 1922, the paintings change radically: now form emerges from color with only a few lines striving towards an integrated totality, based on impressions from the study of nature. The following decade brought fluid watercolors with a focus on humans, reincarnation, and travel to astral worlds. One series highlights the characteristics of human organs such as the kidneys and spleen.

All along, the multifaceted work is deeply connected with occult, spiritualist, Theosophical, and Anthroposophical theories and practices, grounded in Christian faith. Her images were made for meditation, often combining words and images, depicting diverse religions within a spiritual dimension. Whether figurative or abstract, her images resonate with the desire to communicate with other spheres, different realities. In this respect, af Klint shares both the epistemological and the methodological concerns of Orthodox icon painters who adopted principles of representation that distinguished sacred reality from the appearances of the world around us. The “otherness” of the immaterial realm needed to be emphasized. The result is in both cases distinctly non-naturalistic. Af Klint’s work has also been compared with the Tibetan prayer flags designed to honor the gods, with their particular association of colors with divine attributes.

Despite intermissions in her practice lasting several years, af Klint was impressively persistent in her pursuit of a consistent pictorial mapping. It is tempting to compare her methods to those of contemporary practice-based research: in the process of trying to understand and come to grips with something, she tried various sources and means. For example, she experimented with a variety of techniques that allow her to produce many paintings in a short period of time. Other features of her life feel contemporary too, not least her lifestyle: she chose not to marry, lived in same-sex relationships, and worked collaboratively with other women, often even painting on the same canvases.

Furthermore, af Klint shared some concerns with the cosmists: most importantly that dying is not to be considered the end for humans.1 We return as reincarnations, she believed. The struggle against the limitations of earthly life was another common aspect of radical thought at the time, as was the desired and expected overcoming of sexual division and distinction, and indeed the surmounting of all dualities. In addition, both af Klint and the cosmists were politically progressive, even socialist, and were interested in natural science and its new findings. And, like her Russian contemporaries, af Klint’s work was preoccupied with humanity’s place among the planets and the stars.

The claim that af Klint’s work was “discovered” through two blockbuster exhibitions at mainstream art museums in the 2010s is as wrong as the treatment of her work within the art system that these museums represent. Not only does the rhetoric of “discovery” go against the profound spirit of her work; it also misrepresents its purpose. Af Klint did envision a spiral-shaped “temple” in which a series of her paintings would be housed, so the spatial setting of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim museum was apt. But that does not override the important work done on her legacy prior to the blockbuster exhibitions. Furthermore, it is problematic to place the work in ticketed exhibitions—the paintings were made as devotional objects and not entertainment spectacle. It is true that the exhibition drew a record audience but that does not legitimize the disavowal of previous shows, curators, and visitors.

While af Klint did not get the affirmation she desired from Steiner, who admitted on his visit to her studio in 1908 that the paintings were too far ahead of their time even for him to grasp their importance, she neither sought nor received mainstream commercial or institutional support for her work during her lifetime. Although it appears that she was aware of some avant-garde peers (there was an exhibition by Edvard Munch in her studio building in Stockholm, for example), she was not part of that scene. Instead, af Klint gravitated towards likeminded “sidestreams” of culture, where she might find people who shared her spiritual interests and mindset and who were mentally prepared to receive her work. She journeyed to both London and Amsterdam to seek out Anthroposophists who might be more sympathetic to her project, carrying a “museum in a suitcase” filled with full-color miniature replicas of her paintings.

The aggressive commercialization of af Klint’s oeuvre started in the 2010s, in the wake of those blockbuster exhibitions and changes in the board of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Because the foundation holds most of the work, and af Klint’s will states clearly that the work should be kept together, other saleable items were invented to satisfy the new corporate and commercial agenda. Hence, the considerable revenue from ticket sales has been accompanied by a flood of publications, postcards, and posters, which can be expected and even accepted. But the towels, coffee mugs, pillowcases, and editioned hand-knotted carpets cross a line when one considers that these paintings are not simply objects of aesthetic contemplation but aids to spiritual experience. Not to speak of the NFTs that were auctioned in 2022 by the digital art company Acute Art and the publishing house Stolpe, both affiliated with new board members of the foundation. Even the Anthroposophists who the artist stipulated should sit on the board seem to see her as a lucrative savior for their center south of Stockholm, with plans for a Hilma af Klint museum on the grounds.

This has led to a split between the family and other board members, and a public controversy. The artist’s great-grandnephew and chairman of the foundation, Erik af Klint, has recently stated that the board should follow its own statutes, which dictate that the work should only be made accessible to those “who seek spiritual knowledge or who can contribute to fulfilling the mission that Hilma af Klint’s spiritual principles intended.”2 In practice, this could mean that exhibitions of af Klint’s work in museums and galleries will be curtailed entirely, and access to her work restricted to “spiritual seekers” who will encounter the paintings in spiritual contexts untainted by the rampant commercialism of so many contemporary art institutions.

A court case awaits. If the wish of the family wins out, then the circulation of af Klint’s work will look very different in the future. Even if this reaction seems drastic, it is understandable. A moratorium might allow for a respite in which to analyze and assess what is best for the oeuvre and the foundation. The corruption of af Klint’s legacy by the board is not only upsetting on its own, but also a crystal-clear example of what happens when the art world is dominated by commerce. Erik af Klint’s resistance to this trend is encouraging for those of us with little love for the market.

Reflection on the preservation and circulation of af Klint’s work also demands discussion about the nature of image-making and the function of art. We cannot consider her oeuvre without placing it in the wider context of human consciousness and morality, asking what it means to behold works of art that were created clandestinely for an audience of like-minded believers. Wanting to maintain a position beyond the art market is legitimate. But what does it entail to partake in the public sphere of the mainstream art world, and to actively refrain from it?

According to Briony Fer, af Klint created a self-generated and self-generating system of ecstatic “spiritual diagrams.”3 These were directed towards something higher than the spiritual, social, and political status quo as she knew it, but they were not completely detached from the world. After all, the human condition has a spiritual dimension with values other than consumption and profit-making. While Steiner stated that in front of her paintings we can experience the traces of cosmos, I would say that af Klint gifted us a remarkable legacy of making and understanding art differently in this world as well.

-

The cosmists were a loose group of intellectuals, scientists, and artists who emerged from the revolutionary conditions prevailing in late nineteenth-century Russia and were committed to the achievement of a utopian future in which humans would colonize the cosmos and achieve immortality. ↩

-

Quoted in Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Is Hilma af Klint’s Legacy at Risk of Being Locked Away?” ArtNet News, March 10, 2025. ↩

-

Briony Fer, “The Bigger Picture,” Frieze, September 30, 2013 available link ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.