Death, Art, and Spirituality

Anton Vidokle

Anton Vidokle is an artist, filmmaker, and the founder of e-flux. He has worked and exhibited in South Korea numerous times, including two editions of Gwangju Biennale, where he won the Noon Award in 2016, as well as a solo show at MMCA in 2019 and other exhibitions, lectures, and projects.

Research Title Death, Art, and Spirituality

Category Essay

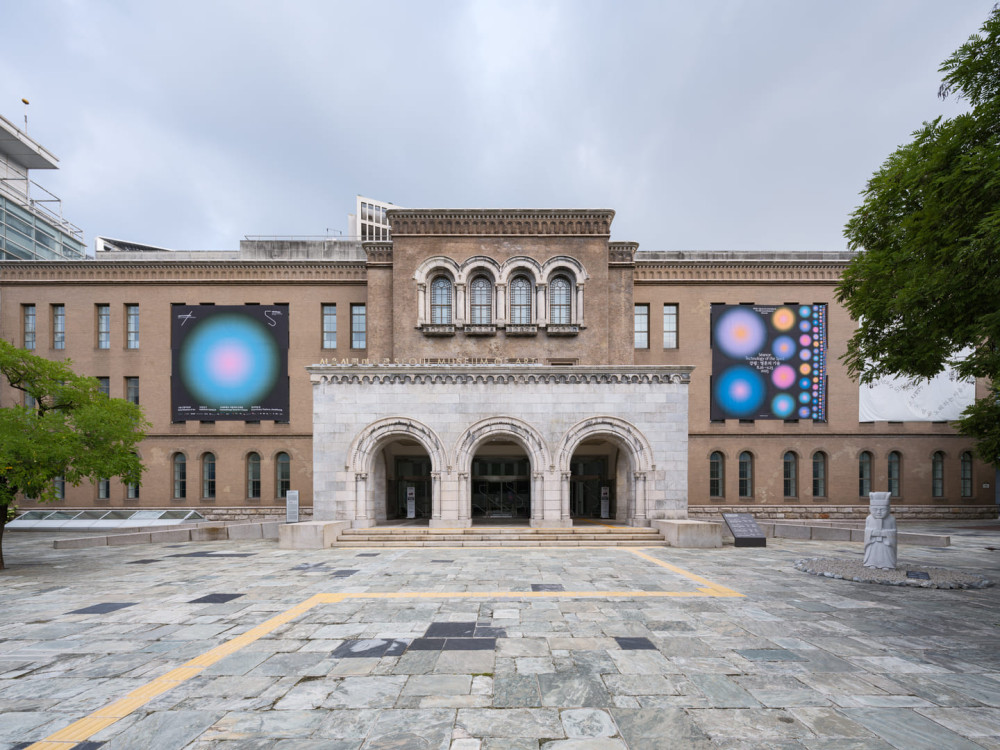

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Anton Vidokle

The centrality of death, the desire for immortality, and the impulse to communicate with the dead have shaped both art and spirituality since prehistory. Many of the earliest works we now regard as art were originally created to commemorate, to remember, to hold onto that which was passing. This funerary impulse is not unique to modern humans: Neanderthals are thought to have decorated burial sites with flowers, while chimpanzees and elephants have been observed arranging leaves and branches over deceased members of their groups. Nikolai Fedorov, the nineteenth-century philosopher, speculated that music, dance, and singing originated from burial chants and laments—and that many visual art forms followed from this same impulse. The Latin word imago, from which “image” derives, also describes the death masks of ancestors displayed in the public spaces of noble Roman households.

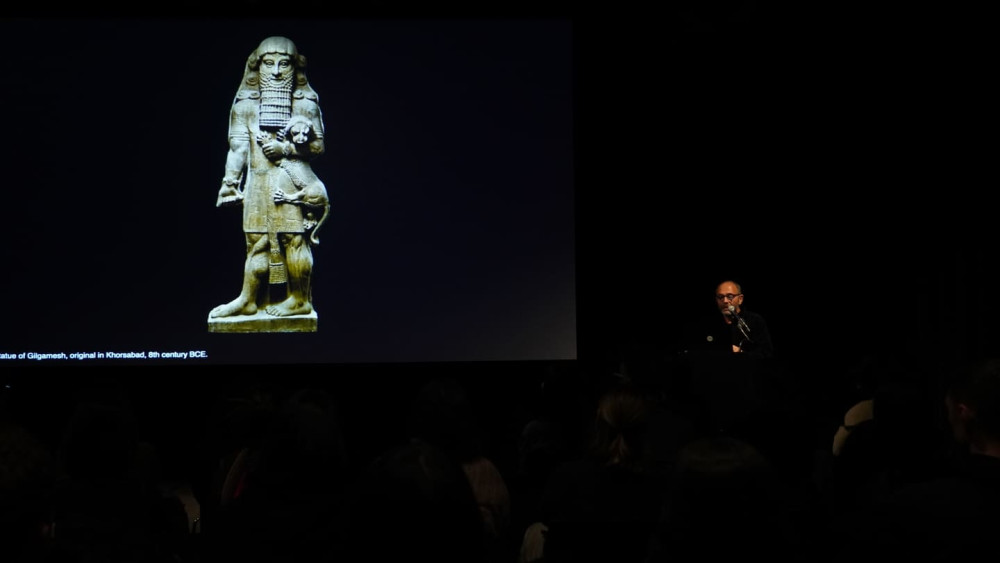

Excavations at Neolithic sites like Çatalhöyük and Jericho have unearthed skulls covered in white plaster, some painted with ochre and inlaid with seashells in the eye sockets. Both eerie and beautiful, these were often buried beneath the floors of living quarters—suggesting a desire not to distance the dead, but to keep them close. The Epic of Gilgamesh, composed in the same region about four thousand years ago and used for millennia as part of a cult, is the oldest literary work known to us. It tells of a king, devastated by the death of his friend Enkidu, who embarks on a journey to find a way to overcome mortality. He encounters gods and demons, and finally Utnapishtim, a Noah-like figure who saved humanity from a great flood. But there is no elixir of life; instead, what endures is the story itself—as a poem, as art. “True religion is a cult of ancestors,” Fedorov once wrote. Perhaps art has always been part of that cult.

In his 1920 essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle,” Sigmund Freud made the provocative claim that “the aim of all life is death.” He meant this quite literally. Freud speculated that since life emerged from inorganic matter, it carries within it a drive to return to that original, inanimate state. Beneath the instincts of pleasure and survival, he proposed, lies a fundamental death drive. This theory diverged sharply from the Darwinian model of survival and adaptation, but it resonates with many spiritual and artistic traditions that center death as both problem and portal—a threshold to something beyond.

Arthur Schopenhauer’s concept of the Will—a blind, insatiable force driving all life and suffering—prefigures Freud’s death drive. Yet Schopenhauer saw art as one of the few ways to momentarily transcend this cycle. In aesthetic experience, he argued, we are lifted out of desire and compulsion and enter a state of contemplative detachment. “Aesthetic pleasure in the beautiful,” he wrote, “consists, to a large extent, in the fact that … we are, so to speak, rid of ourselves.”1

But isn’t being “rid of ourselves” also a kind of death? This idea—of dissolving the self to become a vessel for something beyond—is deeply resonant with artists, and closely mirrors spiritual traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism. According to traditional accounts, the Buddha left his home after encountering four sights: a sick person, an old person, a corpse, and an ascetic. These visions presented both the inevitability of death and the possibility of transcendence. The greatest problem, then as now, was mortality—and the hope of overcoming it.

Georges Bataille also saw transcendence through loss and dissolution, particularly through sacrifice. In The Accursed Share (1949), he described the sun’s boundless generosity—its continual outpouring of energy—as a cosmic surplus that must be expended, sometimes violently, for life to sustain itself. His theory of sacrificial expenditure echoes the Marquis de Sade’s vision of annihilating nature to start anew, or Kazimir Malevich’s call to burn down all museums so that art might be reborn from their ashes.

This radical logic underpins Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov’s essay “Cosmology of the Spirit” (ca. 1950s), which envisions a final act of self-sacrifice: the destruction of the world to repay a metaphysical debt to nature, thereby initiating a new cosmic cycle—an artificial big bang. Nietzsche’s idea of eternal return lingers here: the compulsion to repeat, to renew, to pass again through death as a way to begin.

It is through the act of sacrifice that the sacred is produced, while mystical experience always entails a certain dissolution of the subject, which is also, in a sense, a death. Something similar appears to happen with trance and spiritism sessions, where the body of the medium must be vacated of their individual persona to let something else enter. This is also true of many shamanic traditions, including the Gut ritual in Korea, during which the Mudang—the mediator between human and other worlds—must be possessed by spirits.

Spiritualist and psychoanalytic sessions—as well as cinema screenings—are often described using the word “séance,” a French word literally meaning a “session” or “sitting” and referring to a gathering where contact is attempted with the dead or otherworldly beings through a gifted medium. The word was already in use in the eighteenth century to describe Franz Mesmer’s therapeutic sessions of “animal magnetism.” Emerging alongside modernism, spiritualism—and with it the occult, mysticism, and new syncretic religions—captured both the popular and avant-garde imagination. This fascination was, in part, a response to the disorienting transformations of industrialization and modernity: life was being reshaped by rationalism, regimentation, and mechanization, prompting a counter-desire for mystery, emotion, and escape. We see this in artists across early modernism, from the Theosophy of Piet Mondrian to the Anthroposophy of Hilma af Klint.

Af Klint was part of a group of five women in Sweden who used séances to communicate with spirits they believed to be mahatmas transmitting lost knowledge. While they started with automatic writing, their practice soon expanded to art. Af Klint claimed that her “Paintings for the Temple” series (1906–15) of groundbreaking abstract works was created under spiritual direction: “painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force.”2 Approximately fifty years earlier, around 1861, another female medium, Georgiana Houghton, already started making abstract paintings on paper. Signed with the names of dead members of her family that she was channeling, these paintings are masterful abstractions that represent otherworldly states and passages, which she made with little artistic training or previous experience.

Spiritualism emerged as a religious and social movement in nineteenth-century New York, drawing from the writings of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg and Mesmer’s panpsychic ideas. It held that consciousness persists after death, and that spirits not only endure but continue evolving. The movement traces its origin to March 31, 1848, when two young sisters, Kate and Margaret Fox, reported spirit contact through mysterious knocks in their home. Abolitionists Amy and Isaac Post, Quakers in Rochester, took the girls in and became their first public supporters. Their home, a stop on the Underground Railroad, connected spiritualism with early movements for emancipation and women’s rights.3 From its beginnings, spiritualism was inseparable from radical politics and was primarily shaped by women.

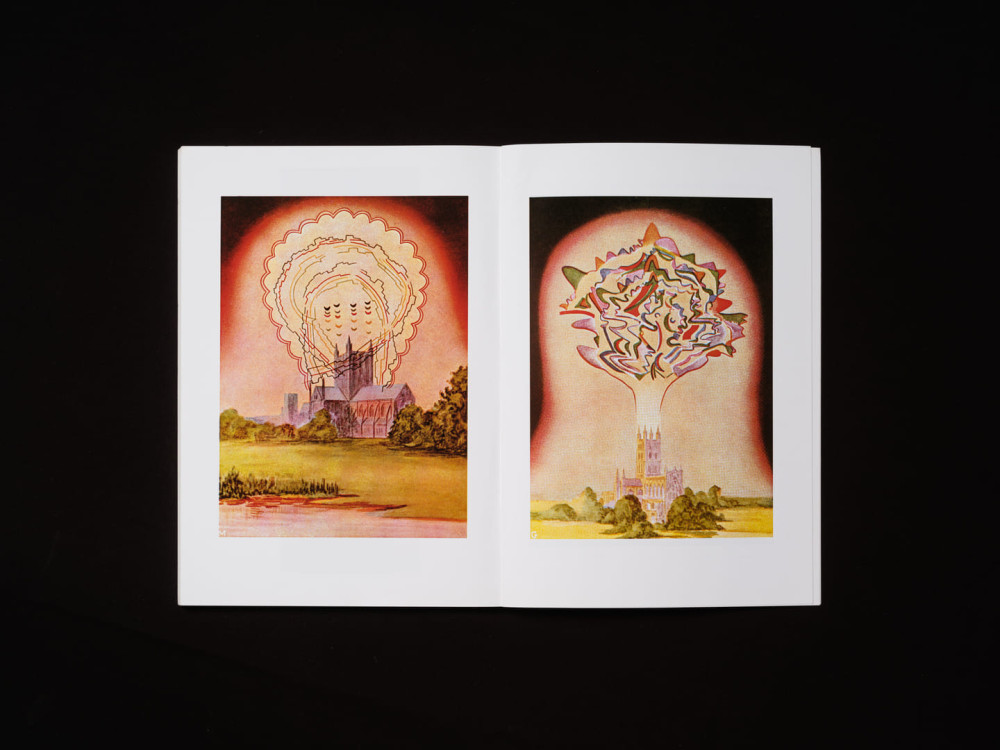

“The world sounds. It is a cosmos of spiritually active beings. Even dead matter is living spirit,” wrote Wassily Kandinsky in 1912.4 His treatise On the Spiritual in Art (1911) outlined a theory of abstraction shaped by Theosophical belief—particularly the idea of thought-forms, immaterial objects produced by concentrated emotion and intention. This concept, articulated by Annie Besant (a disciple of Helena Blavatsky), drew from Buddhist notions of mental aggregates and karma. Besant described thought-forms as entities born of mental energy: “Every thought … becomes an active entity by associating itself … with an elemental … a creature of the mind’s begetting … a world of his own, crowded with the offspring of fancies, desires, impulses, and passions.”5 These forms, she believed, endure and influence other beings they encounter. While “Adepts” could consciously generate them, most people produce them unconsciously.

In 1905, Besant coauthored a book on the subject with C. W. Leadbeater entitled Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigations, accompanied by illustrations from John Varley, Eugenia MacFarlane, and others. These images—vibrational, diagrammatic, and strangely prescient of twentieth-century abstraction—are not just representations, but tools: methods for perceiving the invisible.

Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, was born in 1831 in Dnipro (in present-day Ukraine)—the same town where my mother grew up. I spent time there as a child in the 1970s and recall nothing mystical about it. Yet by the 1870s, Blavatsky had become a central figure in global spiritualism. She merged Western occultism with Eastern metaphysics, particularly Buddhism, and cofounded the Theosophical Society in New York in 1875. Her impact on twentieth-century culture, especially the visual arts, was vast. She was one of the first thinkers to synthesize Western and Eastern esoteric traditions—a tendency that remains dominant in alternative spirituality to this day.

Annie Besant, her successor, was equally complex: a Theosophist, socialist, feminist, decolonial activist, freemason, and medium. She eventually became president of the Theosophical Society in 1908. In 1904, she appointed Rudolf Steiner to lead the Esoteric School in Germany and Austria. Eventually, Steiner insisted on a more Eurocentric focus, emphasizing Christianity—something Blavatsky and Besant opposed. This led to his break with Theosophy in 1912 and the founding of the Anthroposophical Society, based in Dornach, Switzerland.6 The influence of Theosophy and Anthroposophy on art reflects a broader synthesis of Eastern and Western religious thought—from Buddhism and Christianity to Sufism and shamanism. It’s no surprise that, in the post–World War II period, many artists turned toward spiritual practices in Asia, from Zen to newer syncretic movements like Oomoto.

Oomoto-kyo emerged in late nineteenth-century Japan, founded by Nao Deguchi, an illiterate peasant woman from Ayabe in Kyoto Prefecture. On New Year’s Day in 1892, she became possessed by a divine spirit and began recording its messages through automatic writing. These writings were interpreted by the mystic who would become her son-in-law, Onisaburō Deguchi.

What is remarkable about Oomoto is its emphasis on art. Matrilineal by structure, in Oomoto each Spiritual Leader must be an artist—trained in calligraphy, ceramics, traditional theater, or tea ceremony. The religion is pacifist and universalist: it opposed Japan’s military government, was banned during World War II, and its leaders were imprisoned and tortured. In the 1920s, Oomoto even adopted Esperanto as the sacred language of Jinrui Aizenkai, its sister organization dedicated to international outreach. From the late 1970s through the 1980s, it ran an international summer art school, attracting figures like Buckminster Fuller.

Automatic writing, hypnosis, and trance were central techniques in the surrealist movement, which sought to bypass rational thought and access deeper psychic currents. André Breton famously defined surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state,” a method for revealing the unconscious mind. But surrealism’s engagement with mysticism was not merely aesthetic—it was politically charged.

In the 1930s, as fascism spread across Europe, Bataille launched the journal Acéphale—named after the mythical headless figure that served as its emblem. The figure symbolized a rejection of Enlightenment rationalism and the sovereign ego in favor of primal, embodied being. Acéphale was conceived not only as a publication but as an occult society, in which the sacral could be reclaimed through ritual, secrecy, and transgression. According to legend, Bataille believed that the launch of Acéphale required a real human sacrifice to fulfill its symbolic power. He asked for volunteers. None came forward.

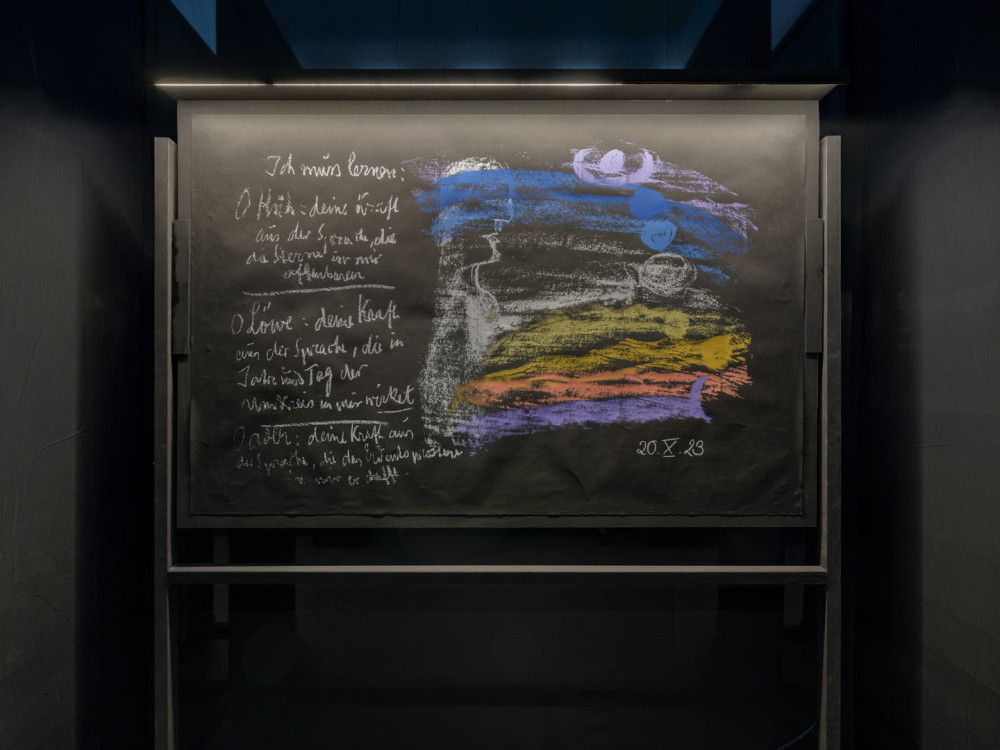

The shamanic dimension of art continued into the twentieth century with figures like Emma Kunz and Joseph Beuys, who approached artistic practice as a form of healing and energetic alignment. Kunz created intricate geometric drawings used for diagnostic and spiritual purposes, while Beuys framed his performances and pedagogical activities as acts of social and ecological repair. Nam June Paik similarly invoked shamanism in his pioneering work with video and electronic media, transforming technology into a conduit for ritual and intuition.

In the final years of World War II, Onisaburō Deguchi created thousands of vividly glazed ceramic tea bowls, in accordance with the principle of Oomoto that art is not simply expression but a channel of divine presence within the human realm. The surfaces of Deguchi’s bowls are densely textured with small indentations made by reed pens or needles, each marking the recitation of a prayer—an act of inscription that merges self, ritual, and material. The luminous, acid-like glazes are said to have been inspired by the eerie colors of the sky as seen from the mountains near Kyoto during the bombing of Osaka.

Today, we are once again living through a profound transformation of life and perception—this time driven by digitalization, algorithmic automation, and artificial intelligence. As with earlier technological upheavals, these shifts have brought about widespread anxiety, disorientation, and a renewed sense of alienation. The global resurgence of nationalism, populism, and authoritarianism is one symptom of this deeper unease. In response, many contemporary artists are turning—once again—to mysticism, spirituality, and nonhuman ways of knowing to make sense of the present.

Artists such as Johanna Hedva, Jane Jin Kaisen, and Yin-Ju Chen draw from spiritual, esoteric, and ancestral traditions as part of their sustained investigations into illness, diaspora, memory, and resistance. Hedva’s work connects chronic illness with occult knowledge and care practices, using performance, text, and sound to explore what they describe as “the politics of vulnerability.” Jane Jin Kaisen often engages shamanism and inherited trauma through film and installation, particularly in relation to the history of Jeju Island and the uprising of April 3, 1948 and its subsequent brutal repression. Her work approaches ritual not as reenactment, but as a form of historical transmission. Yin-Ju Chen combines astrology, Taoist cosmology, and political history to examine how power and belief intersect. Across these practices, spirituality is not framed as otherworldly, but as a structure for making sense of violence, loss, and the possibility of repair.

Our aim with the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale is to produce an exhibition-as-séance: a project that not only presents historical and contemporary artistic practices and discourses that draw on the occult, mystical, and spiritual traditions, but one that enters into conversation with multiple realms that exist within and beyond the human world. Through art, we hope to open channels for the voices of the dead, the ancestors, and those yet to come, making room for their emancipatory potential. In doing so, the exhibition renews a very old task: to hold space for the dead—not in mourning, but in conversation.

-

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, vol. 1 (Dover Publications, 2000), 390. ↩

-

Quoted in Iris Müller-Westermann, “Paintings for the Future,” in Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction (Moderna Museet, 2013), 38. ↩

-

Although in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted they had fabricated their story, the movement had by then spread worldwide, with its own rituals, images, and communities. ↩

-

Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, The Blaue Reiter Almanac, trans. Henning Falkenstein (Viking Press, 1974), 173. ↩

-

Annie Besant, Karma (Theosophical Publishing House, 1895), i. ↩

-

Interestingly, the split between Steiner and the Theosophical Society was rooted in both doctrinal and methodological disagreements—one of which concerned the role of art in spiritual life. In his Munich conferences, Steiner reimagined the Theosophical gathering as a kind of theatrical Gesamtkunstwerk, incorporating drama, sculpture, and painting as vehicles for esoteric experience. This artistic turn, along with his rejection of Krishnamurti as a messianic figure, deepened the rift with leaders like Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, ultimately leading to the formation of the Anthroposophical Society in 1913. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776747/death-art-and-spirituality

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.