Alexandra Munroe in conversation with Anton Vidokle and Koichiro Osaka “On Oomoto”

Alexandra Munroe, PhD, is an award-winning curator, Asia scholar, and author focusing on art, culture, and institutional global strategy. She is Senior Curator at Large, Global Arts at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, where she leads the Guggenheim’s Asian Art Initiative and serves as a senior founding curator of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Project. Munroe has worked on over forty exhibitions and is recognized for her pioneering scholarship on artists Cai Guo Qiang, Daido Moriyama, Yayoi Kusama, Lee Ufan, Mu Xin, and Yoko Ono, among others, and for bringing such historic avant-garde movements as Gutai, Mono-ha, Japanese otaku culture, and Chinese conceptual art to international attention. Munroe was lead curator of the Guggenheim’s exhibition “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World” (2017), which Artnews named one of the top twenty-five most influential shows of the decade. Her exhibition “Yu Hong: Another One Bites the Dust” was named among the “Top 8 Hits” of the 2024 Venice Biennale by the New York Times.

Anton Vidokle is an artist, filmmaker, and the founder of e-flux. He has worked and exhibited in South Korea numerous times, including two editions of Gwangju Biennale, where he won the Noon Award in 2016, as well as a solo show at MMCA in 2019 and other exhibitions, lectures, and projects.

Koichiro Osaka is a curator, writer, and producer based in Tokyo. He is the founding director of Asakusa, a forty-square-meter exhibition space in Tokyo committed to advancing curatorial collaboration and practices.

Research Title Alexandra Munroe in conversation with Anton Vidokle and Koichiro Osaka “On Oomoto”

Category Interview

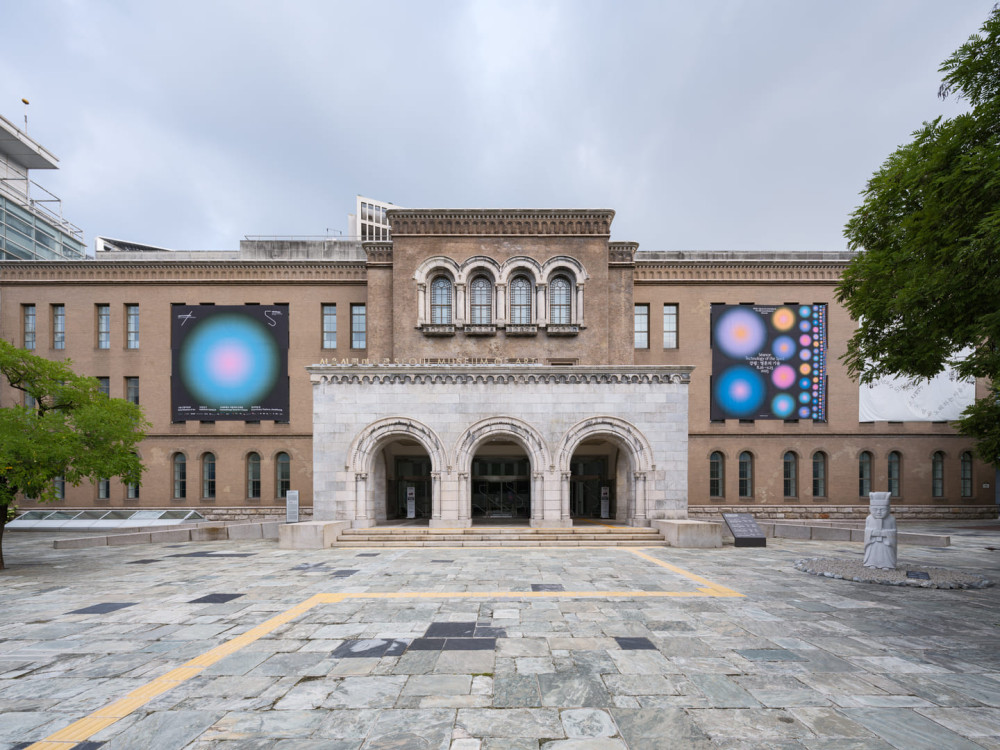

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Authors Alexandra Munroe, Anton Vidokle and Koichiro Osaka

Anton Vidokle (AV): You were among the first students at the Oomoto School of Traditional Japanese Arts, founded by David Kidd in Kameoka in 1976 to advance the principles of the religious order cofounded by Onisaburō Deguchi, whose extraordinary tea bowls we are privileged to present in “Séance: Technology of the Spirit.” You’ve described that experience as foundational to your career as a scholar and curator, which has done so much to advance understanding of postwar Japanese art in the United States and around the world. But before we come to your own relationship to Oomoto, perhaps you could tell us a little bit about its history.

Alexandra Munroe (AM): Here is the history of Oomoto as I learned it. In 1892, in Ayabe, a beautiful rural area in Kyoto Prefecture, a poor, illiterate woman called Nao Deguchi began hearing voices. She became spirit-possessed by a god who declared himself as Ushitora no Konjin, a savior from ages past who had chosen her to transmit a calling to rebuild and purify the world. She wrote down the teachings that she received, eventually numbering two hundred thousand pages, and gained local notoriety as a mystic. She called her writings Ofude-saki (Tip of the brush).

But no one could read this material because it was in Glossolalia, a language that comes directly from the divine and is not necessarily understood by the receiver. So, the story goes that a dashing young man named Ueda Kisaburō arrived in Ayabe. Recovering from a near-death experience and miraculous “travels in the spirit world,” he felt directed to meet Nao, who had prophesized that such a man would appear to help realize Ushitora’s vision. In time, Ueda’s interpretations of Nao’s indecipherable transcriptions became the foundational text of a new religion—more precisely, a sect of Shinto. It was called Oomoto, meaning “great origin.”

Together they founded the Kinmei Reigakkai organization, fusing Nao Deguchi’s revelations with Ueda’s spiritual techniques. Kisaburō married Nao’s daughter Sumiko and adopted the name Onisaburō Deguchi.1 Onisaburō rose to become one of the great orators and philosophers of modern Shinto. He wrote volumes of religious and mystical writings, composed thousands of waka poems, was a designer of shrines, a calligrapher, ink painter, and, as we’ll discuss later in this conversation, a riotous maker of raku ceramics. He was also an outspoken universalist during periods of ultranationalism, taking dangerous political risks and using Oomoto as a platform.

Among the many new Buddhist and Shinto sects emerging during this period in Japan, Oomoto was unusual for being a matriarchy.2 The Spiritual Leader has always been a woman, beginning with Nao and proceeding to the current fifth-generation descendent from the matrilineal line. Another distinguishing principle is that the spiritual practice of Oomoto is grounded in the practice of art.

AV: I can’t think of any other religion in the world that takes art as its departure point.

AM: “Art as its departure point” is beautifully said! Oomoto was devoted to specific practices of traditional art, especially Noh theater and shimai dance. At its forested headquarters in Ayabe and Kameoka, the Bansho-den hall of worship featured a Noh stage, which is like having a full-fledged opera hall in a cathedral!3 This harkens back to early Shinto practices, when outdoor stages were an essential part of the architectural compound of a place of worship in a sacred wood. Originally, there were enclosed parts to a Shinto shrine; nature itself was the site for communion. Noh, or Kagura which preceded it, was a ceremonial dance to summon the gods under an open sky. Its highly symbolic and stylized dance, accompanied by chant, flute, and drum music, was all about the spirit world. A Noh scholar I knew used to say, “Noh is the only theater in the world that begins in the afterlife.”

Oomoto also taught tea ceremony practice and its associated arts of ceramics, calligraphy, and flower arrangement. The headquarters had beautiful gardens and teahouses where its leaders and followers would gather as part of their worship. The sanctuary of Ayabe practices a form of silk weaving using natural dyes and textured silk; female followers of Oomoto typically wear Konohana obi. Aikido, a martial art, was also associated with the rise of Oomoto and was practiced as one of the traditional arts that cultivates harmony and spirituality. The other early Oomoto tenet, as promoted by Onisaburō Deguchi, was the ideal of Esperanto as a global language to unite humanity.

It is interesting that these art forms are all embodied practices, each with its choreography distilled over centuries. For Oomoto, learning these arts was a form of active meditation. Drawing from both Shinto ceremonial tradition and Zen Buddhism, Oomoto saw the arts of preparing tea, calligraphy, or aikido as spiritual practices whose aesthetics traced cosmic energies. These arts were acts of purification and offering, ways of becoming one with your surroundings. It’s all about encounter and communion. In the 1970s, these traditional arts came to form the summer seminar curriculum of the Oomoto School of Traditional Japanese Arts.

AV: Why was Oomoto persecuted in the first decades of the twentieth century?

AM: Onisaburō was an outspoken advocate for pacifism, universal humanity, and oneness among the world’s religions, and openly criticized Imperial Japan’s rising militarism. Oomoto had a huge following in its early years and Onisaburō’s influence, even celebrity, threatened the bellicose ideology of the Japanese empire across the Asia Pacific. So, in 1921, the government shut down Oomoto, destroyed its shrines, and imprisoned Onisaburō.

Koichiro Osaka (KO): Why did the authorities perceive him to be such a threat? Was it because of the way that he publicized Oomoto in the media? Or how he presented himself?

AM: The organization was perceived as a threat to the divine status of the Taisho and then Showa Emperors—who were the leaders of Shinto as a state religion. Onisaburō was often photographed in regalia and riding a white horse, flaunting his own god-like status. But it was really Oomoto’s politics, which were anti-militarist and internationalist, that led to the so-called Second Incident that began in 1935 and lasted through the war. Oomoto was banned and its followers were persecuted. The headquarters with their studios were destroyed and all the property was confiscated. Onisaburō and Sumiko were tried and found guilty of lèse-majesté, and were imprisoned for six years.

AV: When did Onisaburō make the tea bowls that we are showing in the exhibition?

AM: According to Japanologist Alex Kerr: “At the end of Onisaburō’s life, when everything around him had collapsed, he turned to making raku tea bowls, and these were his last gift to the world.”4 Although he was released from prison in 1942 and allowed to return to Kameoka, Oomoto was still outlawed. While World War II raged, bringing growing despair as Japan’s militarist leaders behind Hirohito refused to face catastrophic defeat, Onisaburō turned inward. According to Kerr, in December of 1944, Onisaburō met raku potter Sasaki Shoraku, who had moved from Kyoto to Kameoka to escape the US bombing of Japanese cities in the last year of the war. Shoraku brought with him a fifteen-year supply of raku pottery clay. While imprisoned, Onisaburō had been thinking about making tea bowls that would “express Heaven.” This was his chance. Using Shoraku’s kiln, Onisaburō fired his first tea bowls in January 1945. Over the next year, until March 1946, he produced an estimated three thousand tea bowls in thirty-six firings—using up the entire fifteen-year supply of raku clay in the process. These weren’t just ordinary tea bowls, known as chawan, but rather sun-burst impressionist paintings in three dimensions, made for handling. Some believe that Onisaburō’s brilliant glazes, so contrary to the muted tones of Japanese tea ceramics, were inspired by the firework-like flames of the bombing of Osaka which could be seen over the mountains from Kameoka. After Onisaburō’s death, Kerr tells us, critic Kato Gi’ichiro gave these bowls the name Yowan (scintillating bowl). And that is what we call them today.

AV: Despite these troubles, Oomoto was very influential. It spawned other movements, which have had a very interesting influence on the modern institutional history of Japanese art.

AM: Yes, there were two main spin-offs from Oomoto. In 1926 the spiritual healer Mokichi Okada founded the Sekai Meshiya-Kyō (World Church of the Messiah). Taking a cue from Oomoto’s belief in the health benefits of organic food, he promoted an agricultural system that rejected the use of fertilizers as early as 1936. Like Oomoto, he also believed that works of art cultivate spirituality and that beauty unifies people and inspires world peace. He built an extraordinary collection of Japanese art, establishing the Hakone Museum of Art in 1952 and the Atami Museum of Art in 1957, predecessor to the MOA Museum of Art. Today, these are among the finest museums in Japan. Only, they function as places of worship too!

The most recent offshoot is Shinji Shumeikai, founded by Mihoko Koyama in 1970. Taking Mokichi Okada’s ideas to the next level, Koyama preached reverence for nature, the eradication of illness, and the appreciation of art and beauty as a way to exalt the spirit. Like MOA, she built a superb collection of antiquities spanning ancient China, Pharaonic Egypt, and Japanese art from all ages, and commissioned I. M. Pei to design a building in the mountains outside Kyoto. The Miho Museum opened in 1997.

By the mid-1970s, these offshoots were thriving while Oomoto began losing followers. They felt that they needed a reboot, and this leads me to the extraordinary figure of David Kidd, who was approached for that purpose.

AV: How did you come to know Kidd?

AM: I spent three enchanted years in Kobe as a young teenager in the early 1970s. My father’s work in the pharmaceuticals industry took us there; my mother’s work as an artist kept us there. At that time, the Kansai region [home to Kobe and nearby Osaka and Kyoto] was the center of international business and manufacturing in Japan, rather than Tokyo which was the center of finance and government operations. Kansai was far more cosmopolitan: in Kobe alone, we had British, German, and French schools, as well as schools for Jesuits and for Sikhs. I attended the Canadian Academy in Rokko, founded by Lutheran missionaries in 1911. It was famous for being the boarding school for missionary kids whose parents had parishes in the boondocks.

What’s more, Kansai attracted the world’s greatest “Orientalists,” who would travel there on extended research trips, like the Berkeley Chinese art historian James Cahill or the Tibetologist John Blofeld. At the time, no one could enter China, which was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, lasting until 1976. It was no secret that Japan was the repository of Chinese civilization. So much of Chinese culture had been lost, not only in the twentieth century but in the preceding centuries as well. Japan was a living repository where customs long eradicated in China were part of everyday life, and its Chinese libraries, archives, and collections were the oldest in the world outside of China. And it was during this time, and in this context, that my mother and father, who were intellectuals and artists, befriended an American by the name of David Kidd.

David was an extraordinary character. He was born in Kentucky in 1926, the son of an automobile manufacturer. In his teens, he developed a fascination with China that he attributed to an experience with a Ouija board. He was an exceptionally handsome gay man, and often told me that if he hadn’t left America, he would have been killed. So in 1946, he travelled to Peking to pursue his studies. He fell in with an extraordinary group of expats, like the literary critic William Empson and his wife Hedda, who liked to shock her friends by diving nude into koi ponds. This group also socialized with revolutionaries, artists, mystics, and mandarins. David married into the family of the Supreme Court Justice of China and lived for several years in their Ming palace in the center of old Peking. He wrote up these tales for the New Yorker, and they were later published in book form as Peking Story: The Last Days of Old China.

David became a profound student of Chinese philosophy, aesthetics, and history. He immersed himself in literati culture, learning from his wife’s father. He observed how scholars’ objects were displayed and used, how they marked the seasons and occasions. Unlike the West, where art was something to be hung on a wall and forgotten about, here, in the fashion of the Song court, art was an event—unfolded with select friends and appreciated as a collective but fleeting occasion, aided by wine, poetry recitation, and conversation. Then it was rolled up and stored away, the moment gone.

AV: And then the Communist revolution came.

AM: Right. After Mao marched victoriously into Beijing on October 1, 1949, David watched as many of his friends joined the revolution to build Red China’s new society. But one event changed his mind about staying on. In his father-in-law’s study, there was a particularly important incense burner from the Xuande period. Xuande incense burners are renowned for their composition, made from hundreds of different minerals, including ground lazurite and other rare elements. What made these burners extraordinary was that they only came alive with the heat of the incense, a piece of bark placed on a small bed of red-hot charcoal. In the study, this warmth had been maintained for some four hundred years, sustaining the unique glow of the burner. One day, a young family retainer splashed water onto it, extinguishing not just the charcoal but the very essence of the object. The inner warmth that had sustained its beauty for centuries was gone and could not be rekindled. David and his wife took what few objects they could and left China.

I mention this because David’s connection to the lived experience of East Asian culture was profound. He was deeply interested in how objects functioned: not just their form or their material value, but how they operated within society, what they symbolized, and how they shaped cultural and philosophical frameworks. To draw from cosmotechnics, he saw objects as part of the engineering of a culture: tools that activated thought, experience, and even mental transformation, thresholds to alternative planes of existence.

AV: So how did someone obsessed with Chinese culture, who spoke the language fluently, end up in Japan?

AM: Japan was the closest thing to China for a determined Orientalist like David Kidd. While in limbo in New York in the early 1950s, he met Sen Sōshitsu, the 15th Grand Master of the Urasenke School, one of the three houses of wabi-style tea ceremony descending from Sen no Rikyū. Sen Sōshitsu was among postwar Japan’s charismatic cultural figures who took it upon themselves to rebrand their country from wartime enemy of the West to a true peace-loving modern state—a rhetorical feat orchestrated by the occupying US government, but Sen Sōshitsu was the man for this job. (Sen’s recent death, at the age of 102, was front-page news across Japan, and obituaries around the world lauded him for his “tea diplomacy.” I fell into reverie thinking of the many occasions we had met; he had the presence of a Pope.)

Through Sen, David got a visa to Japan and settled in Kobe. By the early 1960s, he was living in a large Japanese house in Ashiya that had been a former detached palace. He and his partner, Yasuyoshi Morimoto, transformed the rooms into a Chinese-style reception hall, furnished with Ming k’angs and “yellow flowering pear” altar tables arranged with his cherished scholars objects, many of which he had carried with him from Beijing. David became famous for his salons. Erudite, amusing, brilliant, and a nonstop smoker, he held court with people like Buckminster Fuller, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Ingrid Bergman as they passed through for Expo 70 in nearby Osaka. Yukio Mishima’s militia men came by for tea. The Shah’s nephew asked David to build him a collection of Tibetan Buddhist art. Benedictine monks on pilgrimage would stay for weeks at a time, and backpackers en route to Afghanistan would hang out, reeking of hashish. David Bowie came through, was astonished by David, and bought the film rights to his Peking Story; they looked like identical twins. Basically, anyone who was anyone went to see David Kidd. Guests would stay up until two or three in the morning, when he would dim the lights and play Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 or Fauré’s Requiem full blast.

David was fascinated by religion, spirituality, and metaphysics. Much of the art he collected—and occasionally sold to pay the bills—had originally been made for Buddhist worship. He befriended the most influential Zen and Shingon abbots of the day, and his Ashiya house was a haven for exiled Tibetan rinpoches. When Oomoto came knocking, his interest in Shinto took on new urgency.

We lived nearby David and he became inseparable friends with my mother. I would drop by after school and find them dressed in Tibetan gowns reading Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine or Gurdjieff’s Meetings with Remarkable Men. David loved young people and basically adopted me as a protégé. He convinced me that I had destiny with Asia.

AV: And then you moved back to the United States.

AM: I moved back to Connecticut in 1973 and naturally, fell into a deep depression! I pined for Japan, but we stayed in touch with David. And then, around 1975, David received a phone call from Naohi Deguchi, Sumiko’s daughter and now the Spiritual Leader of Oomoto. She summoned him to Kameoka, and said, “I’ve had a dream about you. I dreamt that you are going to come and show us the way forward to recapture the internationalist mission of Oomoto, in this era. You, Mr. Kidd, are going to lead the way.”

So, David goes home and, in turn, has a dream. And he sees the Oomoto School of Traditional Japanese Arts. The idea was that, following Oomoto’s principles, the school would teach the Japanese arts in a unified way to an international community of artists, scholars, and cultural leaders. He and Naohi Deguchi joined forces with James Parks Morton, the great interfaith theologian and then-dean of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in New York, and together, they founded the school. David invited me—rather, commanded me—to join the first class in the summer of 1976. That is when I met Alex Kerr, a Rhodes Scholar fluent in Japanese, Chinese, and Tibetan, who would become a lifelong friend.

The seminar was held on the grounds of the Kameoka headquarters and lasted for one month. The school had modest dormitories, a Bansho-den, several tea rooms, Noh stages, pottery studios, and aikido dojos. The curriculum consisted of classes, lectures, and outings. The classes were called “keiko” [used broadly to mean the practice of an art form] and the deeper spiritual practice was referred to as “shugyō.” These are the terms that express the discipline and devotion tied to spiritual practice—“shugyō” meaning religion or spiritual path. We had extraordinary access to a constellation of enormously influential people in the world of Japanese culture and religion, and felt like initiates into the most esoteric repositories of intelligence.

AV:Why was the emphasis on traditional arts specifically? Was this David’s idea or did it come from Oomoto itself?

AM: Both. David was a great fan of modern music, but he hated modern art; he never understood or forgave me for going into the field. For him, art was a technology for living, a technology for communicating with altered or higher states of consciousness. His true interest was consciousness itself—how to explore it, expand it, and live through it. He experimented with LSD and enjoyed the Himalayan dope that was available in Japan in those days, always seeking ways, in Huxley’s words, to “open the doors of perception.” David believed that’s why we’re here—to reach for the most expansive version of human experience possible.

He focused on the traditional arts because he believed in the past as a resource for regenerating the present. Having witnessed the brutal destruction of Chinese humanism during the revolution, he decried the eradication of heritage in the onslaught of ideological brainwashing or, in the case of postwar Japan, rampant Westernization, industrialization, and modernization. David was a cultural preservationist—not to keep it static but rather to keep it relevant for the most creative minds of our day. He wanted musicians, scientists, futurologists, and artists to access these traditions, to spark new forms of intelligence.

So that was the Oomoto School! I went back for four summers working as an interpreter for the sensei and guide for the students, an extraordinary collection of people from all over the world. Thanks to Oomoto, I thought I was going to become a professional Noh performer, and, while living as a lay disciple at Daitokuji in Kyoto, I came close to joining the Zen Buddhist order!

AV: Why didn’t you?

AM: Being a young gaijin [foreigner] woman in a traditional Japanese system built for men was a little challenging, to say the least! David thought I had lost my mind and all sense of humor. Then, after my graduation from Sophia University in Tokyo in 1982, I was hired by Rand Castile, the visionary founding director of Japan Society Gallery, and I moved to New York. That’s when I discovered a whole world of avant-garde artists from Japan whose stories had never been told, like Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono. But that’s a whole other story.

Yet even as my career and studies took another course, I always knew that, on the most elemental level, Oomoto’s teachings had forged my sensibilities.

AV: And this is where you encountered Onisaburō’s works of art.

AM: Yes. Onisaburō’s calligraphy, ink paintings, and ceramics were displayed all around Oomoto. Everyone we met had stories to tell: about the miracles he wrought, his universalist worldview, the persecution he suffered, and his enduring faith in art as the highest spiritual path. In time, I came to see him as a totally radical artist who deserved recognition within the broader history of postwar Japanese modernism. Of the hundred or so artists I included in my 1994 show, “Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky,” Onisaburō was by far the most “out there.” A cleric? A mystic? An outlaw?

Some years ago, I built a teahouse by a waterfall in the Colorado mountains. I hadn’t practiced tea in decades, but my body resumed the choreography I had internalized at Oomoto. The abbot of Tokuzenji, who had given me my first koan as a novice Zen practitioner at Daitokuji, gave me the name of the teahouse: Tsutenkutsu, “the grotto of heavenly passage.” I began to build a collection but kept dreaming of having one of Onisaburō’s tea bowls. To my delight, Alex finally found one for me. When I opened the box, I found this description he had written:

Onisaburō intended his bowls not only as utensils for the tea ceremony but as Shinto sacred objects in which a divine spirit resides. While potting he recited the Oomoto prayer Kannagara Tamachi Haemase (May We Be Blessed in Accordance with the Kami), which we heard often in the Oomoto seminar. He claimed to have recited Kannagara a thousand times for each bowl.

Near the end of his life, Onisaburō wrote this poem:

Shinryoku wo komete 心力を籠めて

Tsukurishi rakuyaki no chawan ni 造りし楽焼の茶碗に

Tama wa tokoshie yadoru 魂は永久宿る

My heart’s energy infused,

Inside the raku-yaki tea bowls that I’ve made,

A spirit will dwell forever.

-

Deguchi Onisaburō is also remembered as a spiritual instructor to Morihei Ueshiba, who would found the Japanese martial art aikido. ↩

-

Sumiko inherited her mother’s title as Oomoto’s Kyoshu-sama, or religious master. She was succeeded by Naohi Deguchi, her eldest daughter, and so on. ↩

-

Oomoto has two headquarters. Ayabe is considered the sacred origin site, while Kameoka functions as the administrative or working headquarters. ↩

-

Personal correspondence with Alex Kerr. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776743/on-oomoto-a-conversation-with-alexandra-munroe

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.