Unreformed Images

Hallie Ayres

Hallie Ayres is co-curator of the 13th edition of Seoul Mediacity Biennale, was on the curatorial team for Cosmos Cinema, the 14th Shanghai Biennale, and is associate director of e-flux.

Research Title Unreformed Images

Category Essay

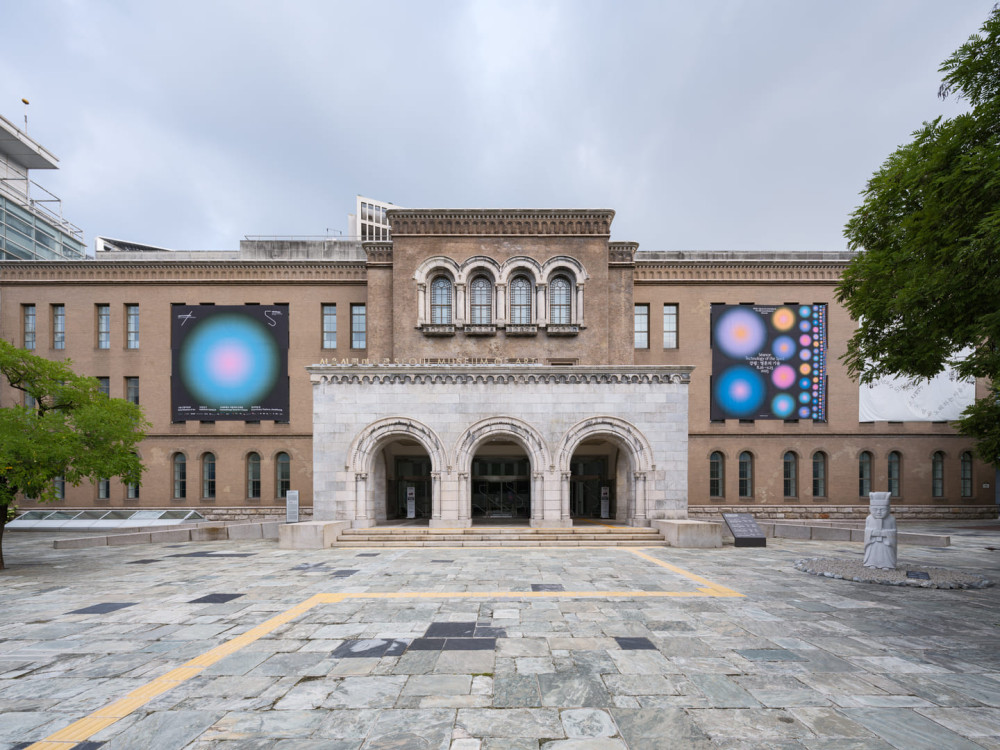

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Hallie Ayres

In 1996, the Virgin Mary appeared on the glass panes of a building in Clearwater, Florida. Rainbow streaks congealed into her simulacra, her head tilted in the iconographic tradition, gazing down from the Seminole Finance Corporation at the corner of highway US 19 and Drew Street. This miracle—that might also have been caused by the corrosion of the metallic coating on the glass—attracted nearly five hundred thousand devotees within the first few weeks of its appearance.

The owner of the building, unconvinced by the scientific explanations and eager to make some easy money, decided to protect the image by turning his building into a religious shrine. He sold the building to Shepherds of Christ, a Catholic ministry organization, which renamed it Our Lady of Clearwater. They erected a large wooden crucifix adjacent to the corroded Virgin and opened a rosary factory in the space that had previously overseen the allocation of preferred equity and debt financing for real estate development. In 2004, a local teen used a slingshot to smash the top panes of glass, effectively beheading the Virgin Mary.

The perception of religious imagery in natural phenomena is nothing extraordinary, even by Florida standards. Anthropologists have suggested that the observation of such signs may approach a cultural universal, a feature of monotheistic belief systems as much as those derived from nature worship, animism, and fetishism. Psychologists attribute this phenomenon to pareidolia, a type of apophenia by which one sees an object, a pattern, or a meaning in nebulous visual stimuli.

The idea that certain images can be imbued with power is equally commonplace. The history of religious icons (and iconoclasm), of talismans and lucky charms, even animism and object-oriented ontology, evidences the extent to which images and objects are believed not only to represent but also to do. It is certainly not uncommon to perceive images in the random patterns of the phenomenal world, nor to ascribe a type of agency or influence to these images.

At intervals in human history, this tendency has been dismissed by both religious institutions and their reformers as superstitious, backward, or heretical. In the Christian tradition, the Reformation marked a schism in which communion with the divine was not prompted by the physical architecture or iconography of the church but by a direct relationship with God through scripture and the experience of congregation. In Martin Luther’s vision of a “priesthood of all believers,” the “true” and “invisible” church was produced by a gathering of believers who had come together to listen to a sermon.

As the art historian Joseph Leo Koerner points out, this revolution in the experience of the divine did not forego images entirely, since in the Lutheran tradition they remained on the altar. Yet Koerner shifts our focus away from the picture towards an analysis of the “machinery of actors, actions, and instruments using the image”—what he deems the “apparatus” surrounding an image.1

Koerner’s argument is that if the Reformation were a movement built on the word of God alone, then religious imagery would have completely disappeared. Yet this is not the case. Foundational to his argument is the Wittenberg Altarpiece, painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1547, which Koerner uses to illustrate that the image itself performs theological labor: “a paradigmatic instrument of a disenchantment of the world—that ‘great historical process’ described by Max Weber, through which magic was eliminated from salvation.”2 These are “reformed” images, shorn, like Protestantism, of superstition.

Such an image, Koerner argues, is not intended to mediate an experience of the sacred for an individual, in the manner of a religious icon. Instead, it is self-conscious of its own status as a work of art. As such, a reformed image cannot mediate but only interpret or reflect:

[Cranach’s] portrait of the iconoclastically cleansed church interior surrounding the cross divides the world neatly between beholding subjects and beheld objects. Even the tableau of a world-renouncing faith displayed religion as it in fact is: a communicative action performed by a given social whole.3

The reformed image redirects the viewer’s attention to what is occurring within the church itself. This is the true site of worship and religious experience, rather than some gated world to which works of transcendental art (as well as the mediating infrastructures of priests and popes) might allow the believer access. This use of images in the Reformed tradition thus allows the devout to make sense of what Koerner deems the “visible invisibility” of the Protestant church.4

Reformed images depend on a separation of the aesthetically beautiful from the religiously or magically potent. In The Power of Images (1989), David Freedberg challenges this distinction, arguing that it is indicative of a widespread cultural reluctance in the West to admit that humans respond to images in any way other than intellectually. Freedberg decries iconoclasm, and, for that matter, censorship, as indicative of an inability to draw a line between the real and the represented. According to him, our brains respond to figural images when they first appear to us as if they were “alive.” Only afterwards do we measure our response through a reassurance that the image is inanimate. This initial response, he claims, is universal, while the way in which we process our response and repress our initial reaction to a figural image is the product of specific cultures and circumstances.

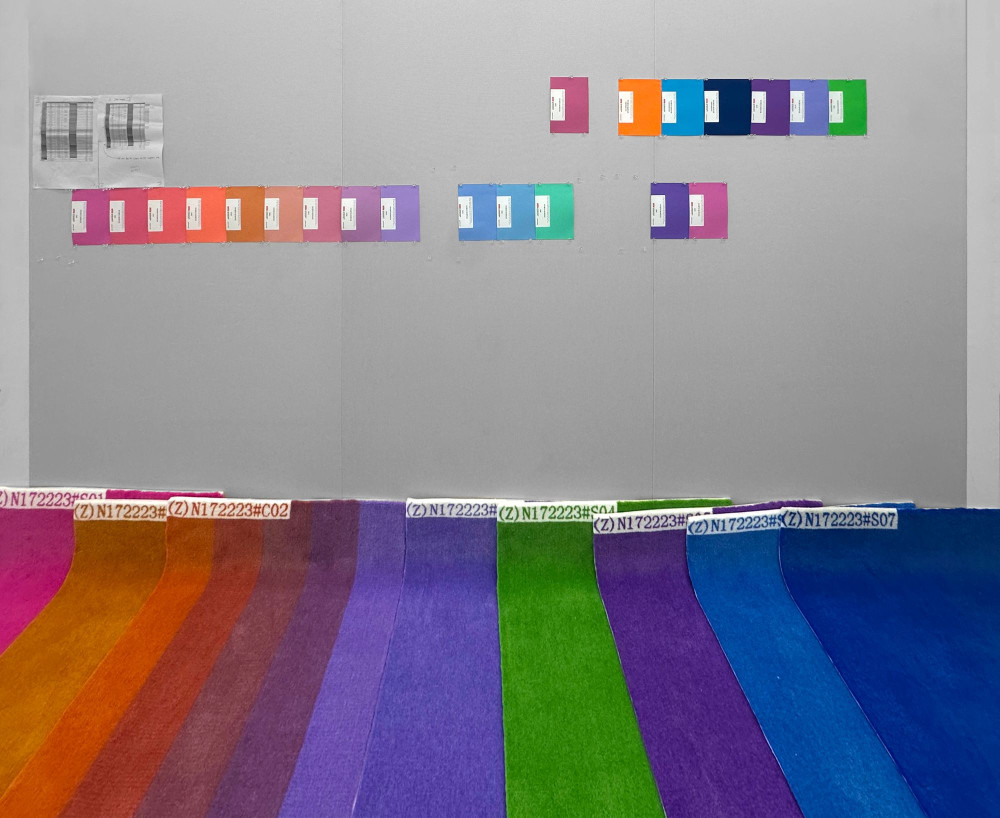

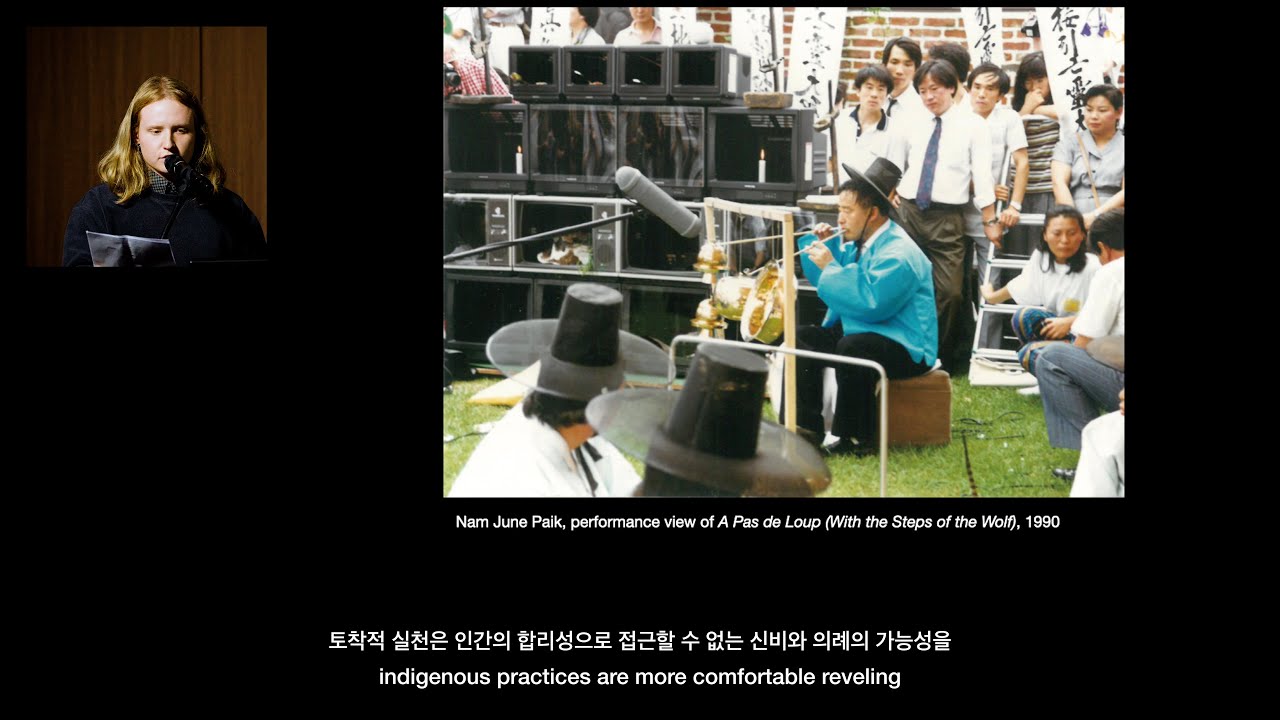

But not every cultural context is so quick to repress the brain’s first impression of images as possessed of life. In Korea, shamanic practices have long relied on paintings as a means of interweaving subject and object. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, many shamans across the peninsula sourced the pictures of gods used in their rituals from the Dongdaemun Market in the Jongno District of Seoul.5 As this was during the period when the government still condemned shamanic practices as “superstition,” and when crusades against shaman shrines were fresh in the memory of Koreans, these shops were reluctant to be labelled as “Shaman supply stores.” Instead, while selling items clearly intended for shamanic rituals—drums, cymbals, gongs, god paintings—they called themselves “manmulsang,” or “purveyors of all kinds of things.”6 “Things”—in other words, objects and images imbued with a pathos determined by the capacity of spiritual practice to serve as a technology with social and political aims.

The flourishing of spiritualist movements in the West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was, at least in part, a product of Fordism, factory labor, and the new alienations of modernity. Theosophy and movements like it were a response to a loss of bodily and spiritual autonomy.

In Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), Helena Blavatsky claimed to have overcome the antagonism between science and religion—and the corresponding separation of body and spirit characteristic of modernity—that developed from Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. In her model of an evolution “on a cosmic scale,” as the historian James Webb puts it, art had the potential to achieve the status of pure spirit, untethered to the material plane.7 In the present, the responsibility of the “artist-mystic” is to manifest objects for visual contemplation that accelerate that evolution of the spirit.

In locales outside Blavatsky’s European context, by contrast, a contemporaneous boom in spiritualism and religious sectarianism was to some degree born of the desire to curb Western influence. Rather than form entirely new belief systems, scholars and religious practitioners tended to redefine existing folk spiritual practices in accordance with a nationalism that sought to construct a coherent national identity in opposition to the West. Paradoxically, this effort often vanquished the very folk practices on which that nationalism rested.

These reforms were apparent across the region in the first decades of the twentieth century. The Yuan Taoism sect emerged in China concurrently with the ancestor-worshipping syncretic religion Cao Dai in Vietnam. In Korea, Cheondoism evolved out of the late nineteenth-century academic movement Donghak, which sought to counter Western influence and the intrusion of Christianity. In Japan, the Shinto sect Oomoto gained popularity, while clairvoyance, hypnotism, and séances prompted widespread fascination, a trend which then travelled to China and Korea.8

During modernization, ruling elites in these countries attempted to eradicate folk practices and faith-based healing remedies, viewing them as hostile to “progress.” While public demand for traditional medicine did not wane, state authorities gradually demanded a separation of medicine from religion. Western medicine was taken to be the only legitimate form of healing—not because it was Western, but because it was based on the rational empiricism that underpinned the entire project of modernity. As art had been divorced from the context of the spiritual beliefs that had once supported it, so now was one’s physical and mental health.

The attempts to adapt religious practice to the demands of modernity took different forms. In Japan, the Meiji-era ideologue Inoue Enryo was a fastidious investigator of the supernatural, even founding the field of “monster studies,” or “yōkaigaku.” Part of his project was to reinterpret Buddhist concepts through Western philosophical doctrines and thereby demonstrate the truth of Buddhism. He sought to use education, modern medicine, and state legislation to “redirect the spiritual sentiments of the masses away from heterogenous complexes of local beliefs in the supernatural and toward a homogenized belief in a unique kokutai (or national essence),” to be found, he believed, in a singular Buddhism.9

In mid-nineteenth-century Korea, at the tail end of the Joseon Dynasty, Choe Je-u established Donghak (Eastern learning), a monotheistic system that was equal parts religion and political theory. Choe preached the rejection of Seohak (Western learning) in favor of radical social reform that included the establishment of human rights and democracy within a nationalistic Korea and resistance to foreign influence. The spread of Donghak among the working classes prompted a series of peasant revolts from 1894 to 1896, with dramatic consequences for the country’s history. By contrast, the Silhak (practical learning) school championed new technologies as instruments of social welfare and advocated a brand of Korean nationalism rooted in Christianity and committed to the suppression of folk beliefs, especially shamanism.10

The nationalist impulse to resist Westernization, then, went hand in hand with the dismissal of folk and spiritualist belief on scientific grounds, as reformers sought to prove that their national cultures were compatible with the standards of Enlightenment rationalism and empiricism. Academic communities sought to debunk mystics and mediums that offered alternative explanations of supernatural phenomena, while political reformers viewed folk practices as impediments to social change. To this end, the symbols and rituals of organized religions attached to the organs of state power gradually came to supersede those “heterogenous complexes of local beliefs” represented by talismans, spells, and spirit possession rituals.

Our own time is also marked by the dogmatic distinction between spiritual experience and science. This seems to preclude any definition of “technology”—i.e., an applied system of knowing the world—that encompasses both empirical rationalism and spiritual practice. This works both ways: in contrast to the late nineteenth century, when “rationalism” was an instrument of power that entailed the rejection of mysticism, today mysticism serves the interests of power, which defies logic and empiricism to promote superstition, conspiracy, and obscurantism. Political leaders, especially on the right, offer magical thinking and arcane theories in lieu of empirical evidence and scientific inquiry. The real is mediated through artificial intelligence, machine learning, and algorithmically collected data. However, as the poet Wallace Stevens reminds us: “There are, naturally, charlatans of the irrational. That, however, does not require us to identify the irrational with the charlatans.”11

One lesson of these histories is to resist the tendency to dismiss ways of understanding the world that run counter to the hegemonic order. Just as the embrace of science should not foreclose spiritual experience, a renewed openness to forms of knowledge suppressed by capitalist modernity need not entail the denial of empirical proof. A “technology of the spirit” resists the separation of material and mind, and allows art to be a means to reconcile ostensibly opposing epistemologies: neither suppressing spiritual practice nor disregarding reason, but adamantly reincorporating the image into an enchantment of everyday life.

-

Joseph Leo Koerner, The Reformation of the Image (University of Chicago Press, 2004), 10. ↩

-

Koerner, Reformation of the Image, 11. ↩

-

Koerner, Reformation of the Image, 11. ↩

-

Koerner, Reformation of the Image, 442. ↩

-

Laurel Kendall, Jongsung Yang, and Yul Soo Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts: The Ownership and Meaning of Shaman Paintings (University of Hawaii Press, 2015), 97. ↩

-

Kendall, Yang, and Yoon, God Pictures, 97, emphasis added. ↩

-

James Webb, The Occult Underground (Open Court, 1974), 90. ↩

-

For instance, the Chinese Institute of Mentalism—the leading hypnotism society during China’s Republican Era (1912–49)—was established in 1911 in Tokyo and only later moved to Shanghai. ↩

-

Gerald Figal, Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan (Duke University Press, 1999), 199. ↩

-

During Japanese occupation, many Korean Christians were imprisoned for refusing to worship the Japanese Emperor; though motivated by theological rather than political convictions, this phenomenon led to a reading of Christianity as a bulwark of Korean nationalism. ↩

-

Wallace Stevens, Opus Posthumous: Poems, Plays, Prose (Knopf, 2011), 228. ↩

The English version of this essay is also availalbe in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776741/unreformed-images

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.