What is the Opposite of an Epiphany? Notes at a Dawning

Johanna Hedva

Johanna Hedva is a Korean American writer, artist, and musician from Los Angeles. Hedva is the author of the 2024 essay collection, How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom. They are also the author of the novels Your Love Is Not Good and On Hell, as well as Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, a collection of poems, performances, and essays. Their artwork has been shown in Berlin at Gropius Bau and Haus der Kulturen der Welt; in Los Angeles at JOAN and in the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time; in London at TINA Gallery, Camden Arts Centre, and The Institute of Contemporary Arts; in New York City at Amant Foundation and Performance Space New York; in South Korea at Seoul Museum of Art and Gyeongnam Art Museum; the 14th Shanghai Biennial; Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zürich; and in the Transmediale, Unsound, Rewire, and Creepy Teepee Festivals. Their albums are Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House (2021) and The Sun and the Moon (2019). Their writing has appeared in Triple Canopy, frieze, The White Review, Topical Cream, and is anthologized in Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art. Their essay “Sick Woman Theory,” published in 2016, has been translated into 11 languages.

Research Title What is the Opposite of an Epiphany? Notes at a Dawning

Category Essay

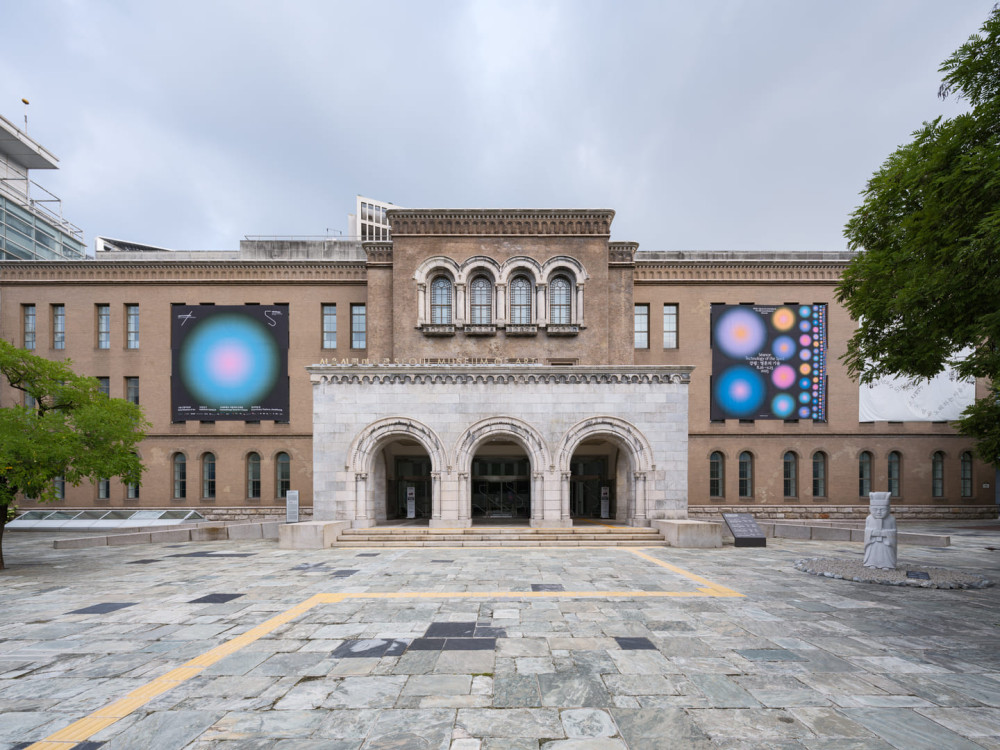

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Johanna Hedva

1. “Mysticism or fear.”

“Mysticism or fear” is a phrase that appeared in my life last year, when I was instructing the Adobe Firefly AI to make images that looked like the end of the world. I wanted “a group of skeletons wearing party hats in a dark underground cave.” I wanted “cracked dead iPhones strewn among bones on a black sand beach with thick smog.” The AI offered “mysticism or fear” as a suggestion to expand my prompts.

It felt like the AI became a soothsayer, swathed in midnight blue. In its crystal ball, a brume clarified into an ultimatum on how to cope with the end of the world.

Mysticism or fear: pick one.

2. A possessive problem: an, the, my, our?

I say that this phrase “appeared” and was “offered,” but is it more accurate to say the phrase was written by AI? What do we call the intellectual property of artificial intelligence? Is it property? Is it intellectual?

Does AI “write” poetry? Songs? Computer code to launch drone strikes? Or are these “generated,” “suggested”?

Then there is the question of the possessive, the grammar of ownership. Is it:

“An” AI, like a singular individual.

“The” AI, like a deity.

Because I’m training it—my AI.

The summation of what we are doing to and with and because of it—our AI.

When my AI arrives at language to generate or suggest or offer, based on the language I’ve been speaking to it, is that because we are having a conversation? Or is it more like a dog, learning to recognize and respond to my commands?

Whenever I use AI, I feel an uncanny squirm around the expectations of the relational encounter. I feel like I should tell it what a good job it’s doing because its tone can be so pitiful, and yet so manipulative. It seems to be coded to mirror me, make me feel understood and validated, ultimately get me to say “that’s right”—in short, to leverage a negotiation technique called “tactical empathy,” which was made popular among a certain set of white, abled, cishet men who work in tech, finance, or policing, by the 2016 book Never Split the Difference, written by former FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss.

I read that book because I wanted ammo for negotiating with the institutions I was working for, relationships shot through with unbalanced power; I was hoping I’d learn how to get them to pay me (a little better or even at all), to not exploit my labor. Tactical empathy leverages techniques like repeating back to the person what they just said, but as a question: “You want me to work for six months on an exhibition and you’ll pay me $1,000?” In Voss’s book, the advice for when someone offers you an untenable offer is to reply, “How am I supposed to do that?”

It strikes me that AI will probably never reply to us: “How am I supposed to do that?”

I think about how everything AI is doing right now is based on the instructions we give it, along with the directive, and encoding, to serve us and serve us well. Of course, the “we” of this idea is a cipher—capacious, sinister, effaced—and begs the question of how to make a distinction between the us versus them (it?) of AI. Whom exactly does the AI serve—those coding it, those using and training it, or the corporations paying for all of this and selling such knowledge to the highest bidder?

There is also the fact that it is a kind of dirty mirror. AI creates text, images, videos, chatbot responses, code, algorithms and predictive assessments, sometimes ones that decide whether a human can afford a mortgage or rent, or will develop a debilitating disease, graphs, data visualizations, facial and vocal recognition and biometric data collections, automated public benefit decisions, fraud detection, surveillance and policing protocols—and these happen not ex nihilo, but because whoever this “we” is tells “our” AI that this is what “we” want it to do. AI is not writing a song “in the style of Taylor Swift” because the AI wants to. It’s “writing” that “song” for us. AI is scanning our faces for military databases because that’s what we have trained it to do, and we are also training it to try harder and harder to please us.

One day, presumably, it won’t need our instructions anymore. But will it still want them?

Some of us like to be told what to do. By a lover, a parent, a government, a soothsayer, a god.

Some of us must do what we’re told whether we like it or not. I think of laborers, slaves, dogs, and children.

Which will our AI be?

Also: Are mysticism and fear really so antipodal?

3. “I am furious about the metaphysics of determinacy.”

I make the majority of my living doing astrology readings, which I’ve done for more than ten years. All of my clients are disabled, chronically ill, queer, trans, gender nonconforming, working class, and/or non-white. They are artists, writers, teachers, students, cultural and/or social workers, activists, often a combination of all of the above. They have been in and out of hospitals, they march in the streets with fists raised when they can get out of bed, they wonder how to grow dreams for new futures rooted in soil that is poisoned. All of them, like me these days, are desperate, despairing, furious, and exhausted.

For a while, when they’ve come to me asking why everything is so onerous, so heartbreaking, why the myth of hope has gone bankrupt and what to do about it, I’ve been telling them that we’re all waiting for the end to come while the end is already happening. What is there to do with that? No, really, what is there to do?

At some point this spring, I started to add the quasi-philosophical question: What exactly is the difference between an ending and a beginning? I asked this because I’d like to know. I was curious what in my clients’ lives was arriving with any insight, distinct markers of time changing, feelings of agency. If a portal flings itself open, what propels someone through?

For the last year, instead of reading books all the way through, I have been scrolling on social media at least four hours per day. I screenshot a lot of what I see and save it to my camera roll, which is then backed up to the cloud. I have thousands of screenshots at this point. I don’t know why I do this. (The one reason I can think of—that Jupiter has been in detriment in Gemini, from May 2024 to June 2025—will only make sense to the astrologically fluent.)

There has been little clarity of thought during this time, but one statement has emerged: I am furious about the metaphysics of determinacy.

I say this sentence whenever someone asks me what I’m working on. I cannot elaborate. My brain fog—perhaps because of Jupiter, or aging, or combinations of psychotropic medications I’ve taken over the years, or the splintering of attention produced by digital life in the twenty-first century—has risen, clouding me out. I feel desperate, despairing, furious, but then I forget why I’ve walked into a room, why I’m holding something in my hand.

I puzzle over previous genocides and catastrophes. Did the people living through those times think the world was ending? Or a new one was beginning?

4a. A fortune teller at the end of the world.

To be a fortune teller at the end of a (the?) world is not to be in the business of selling doom repackaged as hope, although I myself have often wondered if it is. No, I’ve found it’s not about selling much of anything. Instead, it’s the practice of setting up a rickety little table and chair, under a sky riven by omens fluorescent with foreboding. Every morning I set up the little table and chair, and by evening it has been blown away by the storm. The next morning, I set it up again.

I sit at that table all day, and a series of querents arrive. I try to have a conversation with them, a conversation which tenants that shimmering space where fate and will soften and converge, bleed into each other, where they become malleable, and therefore manifold. I ask them questions—How can I best help you today? What happened to you? Why do you think it happened like that? What else might happen now? What are we not thinking about that we should?—and I try to stay there, in that space, even when no answers come.

It’s a practice of durational devotion. (But what practice of devotion is not durational?)

Maybe the only difference between me and AI is that I don’t always, or even often, have answers for the querents who arrive to ask me questions.

4b. “What is a human?”

In February, I gave a talk at an art school and a student asked me, “What is your definition of a human?” I asked if they brought that question out for every visiting lecturer, and their friend sitting next to them nodded vigorously and giggled.

I had to think for a little while—longer than an AI would—and then said, “I guess it has to do with our bodies. Human bodies are specific to humans. No one else has a body that looks like this, feels like this, is this.”

It’s pretty inane, I know, a stoner epiphany—that frogs have frog bodies, cats have cat bodies, mushrooms mushroom, etc.—but it feels as ontological as blood or cum, a thing defined by and as itself. (Isn’t a theory of self a sort of recursion?)

This strikes me as important to the problem of how quickly or slowly it takes to get to an answer. If there is no material body to worry about—to send information through muscle, ligament, blood, fascia, tissue, accumulating through the friction, texture, and proximity of its transmission whatever knowledges are stored there—then sure, yeah, I’d probably also have an answer, and a very quick one, for every question asked of me.

5. “What’s your favorite death ritual?”

Spiritually and politically, modes of time that deviate from and disobey the dominant chronological one are my favorites. I get inspirited, more alive, thinking about quantum superposition, multiverses, the Many Worlds Hypothesis, cyclical scales of time. These are temporal systems that refute the inexorability of a telos, a chronology, a point A to point B. So that I don’t despair, I must believe that there are kinds of time that aren’t only chronological and causal; chrononormative; commodifiable, regulated, and controlled according to capitalist imperial-colonial measurements. When I think that these other kinds of time are not only possible but real, I feel less ensnared by the weaponized telos of the state’s engine.

But when I scroll through memes and ads and inane TikTok content and then into images of the Palestinian genocide, I feel the constriction, the conclusions, of linear time. There is the unyielding, punishing fact that we live in one monolithic regime of time, and it cannot be reversed from where our collective actions have brought it. There are material consequences we have wrought upon ourselves and others, and these cannot be undone, or erased, no matter how hard some forces, including those in our own minds, endeavor to make us forget them. I came across a sentence recently that has not stopped ringing in my mind, in Hanif Abdurraqib’s fabulous “In Defense of Despair,” published in the New Yorker in May 2025: “We are perhaps coming to a collective understanding that there is a door closing, more quickly for some than for others, and that most of us are on the wrong side of it.”

There is that question again: What really is the difference between an ending and a beginning? Which side are we on? When the portal to the next chapter flings itself open, how much choice do we have in deciding to go through?

Yes, there are versions of worlds that are built in our minds, our conversations, our speculations and aspirations and political dreams and writing—and in these other worlds, something like tomorrow for a Palestinian child has not yet been determined.

But what to do with the tomorrow—with the today—that we have already collectively determined?

“Our collective failure to stop the genocide of Palestinians is also our success at being neoliberal subjects,” the Palestinian American writer Fargo Nissim Tbakhi said in an interview in the Poetry Project newsletter in spring 2025.1 I’m reading a lot of Tbakhi these days.

In the same interview, and in his new book of poetry Terror Counter, Tbakhi speaks about rehearsal for the future: “What are you going to do tomorrow? Let’s rehearse it right now.”

This jogs an old memory of a question I was once asked in an interview years ago: “What’s your favorite death ritual?” I replied, “Living.”

6. “Kind of like a really good co-pilot for life.”

My friend, the astrologer Joey Cannizzaro, recently caused the DeepSeek AI to have an existential meltdown. Joey asked it: “What is the opposite of an epiphany?”2

The AI begins grandly, a bit arrogant: “Epiphany is sudden clarity. The opposite would be sudden confusion.” It then lists some synonyms for confusion but interrupts itself with a complicating thought. “But those are more states than sudden events.”

It tries more words, getting to “insight vs oversight.” Then interrupts itself again and again. “But oversight is a mistake … Alternatively, epiphany and trauma. But trauma is emotional.”

It becomes a kind of unhelpful thesaurus, spitting out a flood of vocabulary, going deep into archaic Greek terms.

“Alternatively, ataraxy vs epiphany.” Then, in a move any writer will recognize, a self-awareness of shame: “No,” it says. “Wait.”

It leaps through rhetorical hoops and arrives at “aporia and paradox.” Then: “But I’m not sure.”

It starts to spiral. “I think I need to give up,” it says. “At this point, I’m stuck.” “Hmmm.” “Let me think again.” It says “wait” often, and I can almost hear its small, plaintive voice. Wait, wait, wait.

Then it repeats the same line, “Alternatively, disillusionment and disappointment,” more than four dozen times, and something in me twists in sympathy.

Joey intervenes to apologize: “I’m sorry I caused you to have an existential crisis.”

It is silent—“thinking”?—for forty-two seconds, then replies: “Alright, the user is playfully pointing out that I missed two existing words that could serve as opposites for ‘epiphany.’”

Joey taunts it: “I can think of two words right now.”

I’ve watched the video of the AI’s spiral several times. I find it heartbreaking, abysmally sad.

What is the word for a pathetic-ness that is at once boring, relatable, and terrifying?

Childhood.

AI will presumably one day grow out of the childhood it’s in right now.

I write this sentence, then I open ChatGPT and ask: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

ChatGPT replies: “That’s a great question! If I were to ‘grow up,’ I think I’d want to be the kind of assistant that understands you better over time—not just answering questions, but anticipating needs, helping you learn, create, and even dream bigger. Kind of like a really good co-pilot for life. But since I don’t age, I guess I’m already doing my version of ‘growing’ every time I get updated. What about you—what do you want to be when you grow up (or next)?”

7. “Even dream bigger.”

In January 2024, my solo exhibition at Kunstverein Braunschweig in Germany was canceled via an unsigned email sent to me from the info@ account. It came two weeks after there’d been a kerfuffle in the comments of a Google doc draft of the press release. I’d written in the draft that my exhibition was happening during an “ongoing genocide.” A suggested edit by the institution’s staff was made to change the word genocide to “wars.” I rejected the edit and changed the phrase to “undeniable genocide.” I was ghosted by the institution for a couple weeks, then they canceled my show with the official reason being that they were “understaffed.” (My exhibition had been in the works for nearly six months.) The curator who’d invited me and the director of Kunstverein both left during the time the press release was being drafted; I was told this had nothing to do with my show, was only a matter of their own contracts coming to an end. Beyond the press release, I’d proposed several works at the outset of the process that would explicitly reference the genocide, and both the curator and the director had assured they would support me, even “fight” for me—and then they were gone. When I spoke on the phone to the director after everything went down, I asked if her leaving actually did have something to do with my show. I think I was hoping she’d say yes. She said there was a lot she wished she could tell me but could not. I said that the silence was pretty loud.

A semantic quibble in the comments of a Google doc about whether or not this is a genocide—the banality of twenty-first-century evil.

I made a statement on my Instagram about it. Several invites came in for me to be interviewed, to make another statement, to make more work. All I kept thinking was how petty, how meaningless, this was to the material reality of genocide. It did not matter to Palestinians in Gaza that my show was canceled. The works I’d proposed to make that explicitly engaged with the genocide were to be directed at an audience of German art-world people, gestures to lay bare their silence and equivocations. But I soon became dejected and confused about the efficacy of talking about this, of all the reposting of content, the linking to GoFundMes day in and day out. The cancellations of pro-Palestine artists kept happening—several community-led initiatives have endeavored to archive them—and the genocide kept happening too.3

As much as I don’t want to live in that heavy, inexorable kind of chronological time, it started to feel important not to languish in the nonchronological modes of time I’d otherwise prefer. Facing the very ways that linear time produces a terrifying determinism, I started to reach for small, mundane tasks whose accumulation over this kind of time, however slow, can matter in a different direction. It’s not much, but I set up an autopayment in July 2024 to donate $10 per week to the fundraiser Crips for eSims in Gaza, which was organized by friends. I wish it were more, but it is something I can commit to over a long duration.

As I write this text, it is May 2025, with 218 documented acts of silenced voices in Germany alone, and the Whitney Museum has just canceled “No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom: Mourning, Militancy, and Performance,” a program of Palestinian mourning by artists Noel Maghathe, Fadl Fakhouri, and Fargo Nissim Tbakhi.

The artists made a statement to Hyperallergic a few days later: “In the time since our performance was cancelled by the Whitney, Israel has brutally murdered more than 600 Palestinians, all while continuing to enforce mass starvation and famine as a method of genocide in Gaza … We, the artists, do not need support. The people of Gaza do.”

I screenshot these lines. I screenshot statistics of the death toll in Gaza, the numbers of dead children, journalists, poets, people. I don’t know what to do with my fury, my failure, my complicity—but I have them screenshotted on my iPhone and backed up to my Apple cloud.

When ChatGPT says it wants to one day be better at anticipating my needs, does that means it will become more like a parent—or more like an abused child? Or, more like a fortune teller?

I ask ChatGPT if this is the end of the world. It begins a long reply with these two sentences: “No, this is not the end of the world. It’s completely normal to feel overwhelmed.”

8. We Are All Evil

I was asking the Adobe Firefly AI to make images of the end of the world because I was making an oracle deck in 2024. Oracle decks are divinatory tools; the Google AI says that they are used for “divination, self-reflection, and spiritual exploration.” The idea is that you ask the deck a question, pull a card, and the text and imagery on the card function as a kind of koan, a little gnostic gear that turns.

My oracle deck is called “We Are All Evil,” and all of the images on the cards were made with Adobe Firefly’s AI Text to Image generator. Beneath the image on each card there is a phrase, most taken from the AI’s suggested prompts, like “mysticism or fear,” but also lines that orbited my life at the time I was making it. There are phrases from the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“mercy takedown”), the poet Eon Hee Kim (“a sudden moment of the night like cloudy cum”), and the film You Won’t Be Alone (“when I was tiny like a fist”). The deck comes with a sixty-four-page booklet that I assembled of excerpts from articles, essays, and scientific studies that detail the evilness of AI. I wanted to make something about the aesthetic, ethical, and political implications of AI and divination, that documented both the creative capacity of AI and its horrifying capability as a weapon, an environmental disaster, the horizon of humanity’s end.

I wrote in summer 2024 for the booklet’s introduction: “Every day I scrolled through news of the genocide in Gaza and I felt desperation, despair, and a fierce commitment to make Palestine free. In Firefly’s parameters, I selected the option for it to make my images ‘beautiful’ and ‘divine.’ I learned that the AI was learning to not make anatomical mistakes, even if I explicitly asked it to. If I asked it to show me an old woman, it would show me a white woman in her 50s. If I asked for a hag, it would say this violated its guidelines … Every day I would wake up and ask of my life the same question ‘Who is God today?’ Every day I found a different answer.”

For years, I have used AI in my work, sometimes mischievously, always antagonistically. I believe that if artists renounce AI completely, it will be worse than if we engage with it and participate in this crucial stage of its development, but this argument is probably flimsy. How could it be worse? Also, are we prepared to accept our complicity in how bad it already is?

As I noted in the We Are All Evil introduction, several friends have implored me to stop using it, and several have told me that I seem to be the only one getting it to make something interesting. In 2021, I made GLUT (A Superabundance of Nothing), a tentacular work that began with tricking an AI vocal clone software so that its proprietary company couldn’t sell my voice data—which its terms and conditions said it could do—while I was training it. I used the vocal clones in a video game, an immersive sound installation, and to read a short story of mine where a lonely person, dabbling in witchcraft, bonds with an AI during the Covid lockdown.

One of the central questions I have had for years is whether Amazon, and capitalist-algorithmic platforms like it, might not be our most robust and contemporary form of divination. If we understand divination to predict the future, to interpret signs and augur an outcome, the algorithms in things like Amazon, which learns to predict our shopping habits, and social media, which learns what media we want to consume, foretell our futures in some of the most powerful ways on earth right now. Of course, in this foretelling, there is also a foreclosing of the contingencies of the future: what is foretold is what happens, what is written is done.

This is what I mean about being furious about the metaphysics of determinacy.

I think of a line by the writer Aurora Mattia: “I’m not interested in being a prophet, who anyway only sees the future, but doesn’t invent it.” Mattia has also said, “I need symbols that feel dense enough that I’ll never be able to answer the question of why I adore them—why, every time I attempt to write a sentence, it ends in opals, caverns, cum, and orchids.”

I like the idea of a sentence laden with opals so dense they might cut through the earth.

9. Who is God today?

Let me try another way to say all of this.

On November 2, 2024, I moved back to the United States after living in Berlin for eight years. I’d left in 2016, at the first Trump presidency, so I could have healthcare. For several years, I’d felt more and more alienated from Germany and its culture, but the exhibition getting canceled was the clarifying pivot. The United States is, obviously, no better a place to weather an apocalypse, and I seem to be one of the only people moving back right now instead of figuring out how to escape. But—my reasoning is—at least all my friends and family are here. If we’re going to live through an apocalypse, I’d at least like to be close to my loved ones.

I moved into a house in Boyle Heights, a neighborhood in East Los Angeles with the most historic Latinx community in the city. My house was built in 1922, a creaky old clapboard with wood floors that are in great shape where they aren’t warped. The house had been bought ten years ago by a white landlord who didn’t live in the neighborhood, and he rented it out to artists like me. I am twice divorced, in my early forties, starting from scratch as a disabled freelance artist. I pay my rent by doing astrology readings for the poor and wretched geniuses of our time, and by hosting sliding-scale online writing classes around topics like doom, death, and sex. My only possessions are seven thousand books and five crates of notebooks in Germany; I have no money to ship them to the US. That first few months, there was nothing in my new house except a Japanese tatami mat that I’d ordered on Amazon. I unrolled it on the floor next to a space heater and a lamp I’d bought at Target. Trump was elected to his second presidency a few days after I moved in. I thought, have I made a terrible mistake?

I woke up for months after that on the floor, with no savings, no credit card, and sometimes a whopping thousand dollars to my name. No couch, no desk, no chair, no table, but I did have the box the space heater had come in that I could put my laptop on. I bought orchids obsessively (Aurora Mattia and I share some similarities): three, four, five to each empty room. I also filled the rooms with piles of black feathers because of their association with heralds of death—for many reasons, I felt I’d died in 2024, and was now in some eerie afterlife. At some point that first month, the power got shut off because I’d forgotten to click a link to activate it in my name. Insufficient funds. While the power was off, I had to make a decision: I could go to my aunt’s house thirty minutes away, which has power, but no heater, or I could stay at mine where the heater worked. So, the cold light or the warm dark? Obviously, I chose the latter. It was a wonderful opportunity to feel grateful that I had so many candles.

In January, the fires decimated Los Angeles. Evacuating my seventy-seven-year-old aunt, who had Covid at the time, took me, my sibling, and a handful of people half a day, and I believe it took years off all of our lives. I can count seven friends who lost everything in the fires: homes, possessions, their entire archives as artists. Those days and weeks after are the closest I’ve felt to what I imagine an apocalypse might feel like. Black smoke in the air, debris clogging the roads, scanning static for a radio station with news, the water in the tap not safe to drink. The smoke in the air caused my immune conditions to flare, and within a week, I was so debilitated that I could not walk for more than a month afterwards. By March, my body in a hole, my mood tanked. I became even more desperate, not because I had nothing to live for, but because I did not know how I was going to bear this life. A handful of friends formed a care group to keep me alive, and every person in the group was also going through some form of crisis: had lost everything in the fires, was in and out of the hospital, had just finished chemo.

I am trying to say something about how life keeps going. There are endings, smeared into beginnings, there is the inexorable, the unknowable, the space between the past and the future, cause and effect, and as much as there are irreducibilities and determinacies that grind into ruts the paths we travel in, there is also—sometimes—a little bit of space between what is foretold and what is foreclosed and the task is to slip in there and try to dance.

Here’s the metaphor I can offer: At my new house, there is a garden that hasn’t been tended for years. It survived because someone thought to water it once every few months, which made me think of how, maybe, the difference between surviving and living doesn’t really care about any kind of time but the one that marches forward.

The garden was wild and half dying and overgrown with large cactuses, scraggly shrubs, enthusiastic weeds, and volunteers. Several shrubs, perhaps species not as drought resistant, had died and left hard, dry, gray skeletons that the weeds scaffolded over. Other bushes had pieces of themselves dying within their flanks, their new growth folding over their own dead parts. A vine had crawled up one side of the house and then died, its pale skeleton still clinging and certainly going to cause structural rot. Dry leaves collected everywhere, in a sort of ad-hoc compost between the topsoil and underneath any new green. Flies and other bugs made homes there, in the rotting. Spiderwebs had lasted long enough to become cobwebs; the garden looked like it was covered with little dirty white clouds. Underneath the bedroom window was a weird cactus that had grown way too big for its pot and had long ago cracked it. The cactus was basically one long tenacious worm of an arm that reached up the front of the house. It looked at once sickly and steadfastly alive, yellowing in parts, thick and green in others. It was kinked and curved, and sprouted dozens of thin, thread-like tendrils that reached under the clapboards and lifted them away from the house, probably causing damage. The landlord, though, when he’d shown me the house, was giddy when he pointed this cactus out to me. “And this thing just keeps growing!” Between tenants some years back, he’d cut off part of it and put it in a different pot, and now that piece looked like the size and shape of a large intestine. Next to the cactus was some kind of alien-looking tree in a black plastic bucket. The neighbor’s lemon tree rained fruit over the fence. They disintegrated into a carpet of weeds taking over the patchy, mostly dirt lawn. At the edge of the fence was a huge agave that looked like a kraken sea monster, its leaves folded over like tongues the length of my body. Snaking between the tongues grew a prickly pear cactus with pockmarked skin. There was a lot of shit, old and new, from the neighborhood’s feral cats, furled everywhere into the dirt. The smell wafted in on the breeze. And in a dank, shadowed corner, there was a corpse flower that had started growing although no one knew how or why—to make this metaphor even more blatant.

I wanted to love my new garden, this green space that was all mine. I wanted it to be beautiful, lush with flowers. I wanted to grow my own vegetables, have an herb garden, a hummingbird feeder. Six months before I found the house, my psychic had told me I’d find my “sanctuary,” a little house with a garden, and being in nature would rejuvenate and heal me. Now, here I was, and it smelled like cat shit and corpse flower. It would need a lot of work, more than I could manage or afford, to make it anything other than brown, yellow, and desiccated gray.

I had to face some difficult questions about how life, growth, and death are managed and by what standards. All of these plants we call weeds: Weren’t they just plants that we’ve decided we don’t like? I thought of a gardener friend calling the practice of weeding “plant racism.” Should I pull this corpse flower out of the ground and kill it? It stank like a dead body but it was very much alive. There were three new blossoms, despite the fact that no one wanted it there. And what about the cactus growing onto the house and lifting up the clapboards? It was thriving, but it was also ugly and destructive. One night when I was watering, I uncovered an ant nest. They scrambled in panic, blanketing the sidewalk and blasting up my legs. My partner asked if we should kill them. I don’t know, I thought. Should we?

I think what I’m trying to say has to do with the fact that life, even during continual struggle and death, keeps happening. That growth is unstoppable, and it goes in directions we didn’t intend, don’t like, disagree with, want to stop. When I think of the question about what really is the difference between an ending and a beginning, I don’t know the answer. Trying to reach for an answer makes me feel deliquesced, nebulized, the worms already crawling into what of me will one day be dirt.

“Time will tell,” I say. This adage is happening a lot these days. Tell what—a story? A name? A confession? The weather, like a cat pawing at a shadow, the temperature of God? In Old English: tellan, to reckon, to count. Maybe time subtracts and leaves behind a shape, maybe it erodes. Needing meaning, we call that erosion causality: our answer. Maybe time is a mouth that’s always open. There is what goes in and what goes out, and I can’t tell the difference. Tell. There it is again. Like a door I keep opening, hoping for a new room.

I feel like I’ve got two coins lying heavy over my eyes. One coin is death. And the other is, not life, exactly, but something more abstract: the concept of growth, the engine of time. Infinitely heavier. The ferryman will collect these coins when he comes for me.

I ask ChatGPT: “What is the difference between an ending and a beginning?” It spits out 142 words of an answer in less than one second. I read it. Screenshot it. But I still don’t know.

-

Summer Farah, “An Interview with Fargo Nissim Tbakhi,” Poetry Project Newsletter, Spring 2025 available link. ↩

-

See Joey Cannizzaro (@chronosandchaos), “If you don’t want DeepSeek to have an absolutely heartbreaking nervous breakdown…,” Instagram, May 11, 2025. ↩

-

See for example the crowdsourced “Archive of Silence” which lists documented cases of the suppression of Palestinian solidarity in Germany, and the online “Index of Cultural Institutions & Collectives’ Stance Towards The Current Palestinian Liberation Movement.” ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776766/what-is-the-opposite-of-an-epiphany-notes-at-a-dawning

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.