Who Speaks During a Séance?

Nikolay Smirnov

Nikolay Smirnov is a geographer, curator, and researcher, working with geographical imaginations and the representations of space and place in art, architecture, science, and everyday life. His practice focuses on analyzing and implementing complex narratives through texts and exhibitions. Smirnov studied at the Geography Department of Moscow State University and the Rodchenko Art School (Moscow). Co-curator of the projects Metageography (2014–2018), Arctic Biennale Permafrost (Yakutsk, 2016), Nikolay Smirnov participated in the main projects of the 5th Ural Industrial Biennial (2019, curator Xiaoyu Weng) and the 2nd Riga Biennial (2020, curator Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel). In 2025, Smirnov co-curates the performative workshop Liberating Esoterics? Anti-authoritarian Re-appropriation of Esotericism by Art (Casco, Utrecht, 2025), prepared on the base of his 4-years curatorial research Eurasian Alchemy. His interest in esoteric knowledges comes from the geographic studies of spatial meaning and geo-imaginations. Smirnov’s research texts are published in many collections, such as Enfleshed: Ecologies of Entities and Beings, and on the platforms e-flux, syg.ma, New Age in Eurasia and others. In 2023–24, he was a research assistant at the documenta Institut (Kassel, Germany). Since 2024, he has been a research associate at Kassel University and in the interdisciplinary Research Training Group Organizing Architectures.

Research Title Who Speaks During a Séance?

Category Essay

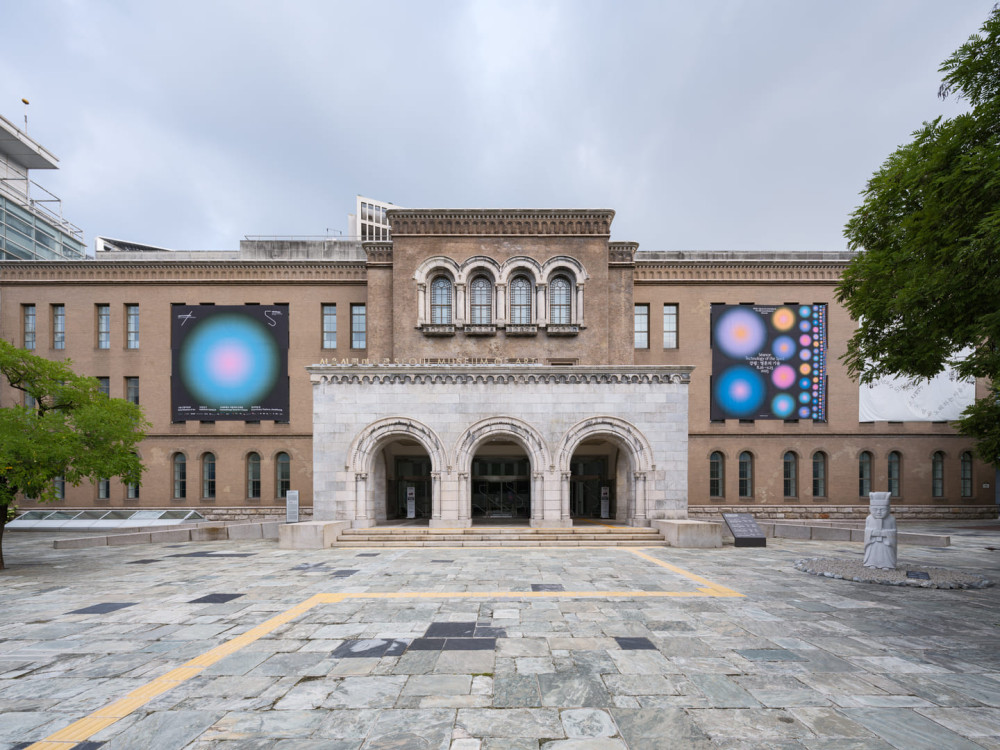

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Author Nikolay Smirnov

The question of who speaks during a séance is not as simple as it might seem.1 The answer given is not only a marker of the historical moment but also reflects the beliefs and aspirations of those who seek to communicate with the spirit world. In our decolonial moment, the spirit of any human (or animal) who speaks through a medium is also seen to represent something larger than itself: a repressed tradition or more-than-human world oppressed by the forces of anthropocentrism, imperialism, and capitalism.

Spiritual Traditions as Mirrors of Emancipatory Theory

The trends of post-Renaissance esotericism, nineteenth-century spiritualism, and New Age spirituality are often linked to the rise of empirical science, materialism, and rationalism.2 But these spiritual movements/practices were not negations of secular thought so much as adaptations to it, which also means that they were forms of acceptance. In other words, these alternative belief systems were not only reactions to materialist science, positivism, and what Max Weber called the “disenchantment” of the world, but also their products.

Occultism and spiritualism were post-Enlightenment adaptations of esotericism to the age of science and technology, when the esoteric principle of “correspondences” between different levels of being was combined with Newtonian causality. Antoine Faivre, the founder of esoteric studies as a scholarly field, observed that while occultism arose in the era of technical progress as “a counter-current” to the “the triumph of scientism,” its followers generally “do not condemn scientific progress or modernity. Rather, they try to integrate it within a global vision.”3 Wouter Hanegraaff further contends that the paradox of spiritualism, this “secularized esotericism,” is that “its essentially positivistic and materialist philosophies were … defended as viable alternatives to the very worldview of which they were an expression.”4 Spiritualism is not opposed to modernity but “a religion perfectly suited to modern secular democracies: not only did it promise ‘scientific’ proof of the supernatural, but its science was non-elitist as well. In principle, every civilian could now investigate the supernatural for him/herself.”5

The study of religions and modern secular movements informed the tenets of esotericism, such as a belief in a “Living Nature” with its own vital force. The New Age movement continued this process, so that, according to Hanegraaf, it can be understood as “esotericism in the mirror of secular thought.” This essay contends that, in the present period, which I call a “late New Age,” both “Western esotericism” and Indigenous spiritual traditions should be understood as mirroring contemporary secularization.6 The resurgence of esoteric and shamanic art practices today should be understood as a reaction to a prevailing sense of lost identity and the influence of decolonial politics.

Different spiritual practices mirror developments in the secular realm. For example, in the context of contemporary art, the presentation of Indigenous spiritual techniques reflects decolonial or anti-capitalist aims in secular society; the late New Age in a mirror of radical thought. For the communities actually practicing these techniques, they might serve as means of forming a communal identity, irrespective of the broader ideological implications attached to them when presented in a museum or gallery. This doesn’t mean that those interests cannot coincide in a common project.

This essay also claims that these processes meet in the spheres of art and culture. Let’s look at the example of Sakha cinema, which is both important in the formation of Sakha identity and has been internationally heralded as a “decolonial” form. Spirits in Sakha cinema can be interpreted in various ways, but they typically reflect developments in secular thought.

The Spirit of Sakha Cinema

The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is a large Siberian republic located in the far east of the Russian Federation.7 Its thriving independent film industry has gained an international reputation for work—typically in the native language and often adapting local mythologies—that serves as a vehicle for the Sakha identity. Each film in the field is not “an end in itself,” but a “statement of a small nation that at some point decided to make cinema a means of fighting for its identity.”8

Mystical stories about spirits are central to this tradition. The twenty-minute film Maappa (1986), made by Alexei Romanov as his degree project at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, was the first to be shot in the Yakut language.9 The plot is as follows: a young traveler named Yld’aa nearly freezes to death in the snow, but is saved by a beautiful young woman, Maappa. They fall in love, but Maappa tells Yld’aa that she is the restless spirit (üör) of a girl who committed suicide because people believed she was contagious. Maappa is doomed to wander between worlds until someone gives her body a proper burial. She asks Yld’aa to do it, and he fulfils the promise. Afterwards, he immediately finds his way home. Maappa adapts a story by the Soviet-Yakutian writer Nikolai Zabolotskii-Chyskhaan (1907–87), chosen by Romanov because he “dreamed of a Yakut cinema … like Japanese or Italian, of our people having their own national cinema.”10

In many cultures, restless spirits in the afterlife become evil. But as the researcher of Sakha cinema Eva Ivanilova has noted, Maappa is not evil but dangerous in a very peculiar way, in that she “resembles a photograph—a material, visually attractive object that carries within itself both an imaginary and a real danger—a mutilated memory.”11 Critic Robin Wood has interpreted monsters in horror films as repressed images of the self—displaced Others, threatening “normality.” Reading Sakha horror through this lens, Ivanilova concludes that “the construction of national identity in Yakut cinema results in the invention of a kind of monster—a ghost who wants to remind the living who they could have been and who they should become … not as the absolute Other, but as themselves.”12

For Romanov, it was inevitable that Sakha cinema would be rooted in mysticism. This was a function both of the culture of his generation, in which “oral folklore was embedded in our souls, so it was natural that [the first Sakha directors] turned to what we knew: our folklore, traditions, legends,” and personal circumstance, given that he had “loved collecting legends, fairy tales, and traditions” since childhood.13 To understand better the relation between a spirit representing the past and future of the Sakha people, and the founding identity of the Sakha nation and its citizens, we need to consider another Romanov film, Saaskí Käm (The Childhood We Didn’t Know) (2017).

Based on an epic novel by another Soviet-Yakutian writer, Nikolai Mordinov-Amma Achchygyia (1906–94), the film tells of how the revolutions of 1917 disrupted the traditional, ethnic way of life of a nine-year-old Yakut boy and his family. Romanov wanted to show the youth of today “the childhood that they did not know” so that they might “remember this different childhood, see it and return to it.”14 In this respect it shares common ground with Maappa, another story about falling in love with something that no longer fully exists, a ghost. The tragedy is that this love can be realized only in the afterlife. Nevertheless, the love of the living for the dead—manifested in the spirit of Maappa or in the image of “unlived” childhood—helps to heal historical traumas and allows the characters in these films to find their own way in the world.

That traditional childhood was phantasmatic for the director, who describes himself as having grown up with “a dream of building communism, of shaping an equal human unburdened by ancestry and traditions.”15 Romanov’s creative process, in close collaboration with his wife, the ethnographer Ekaterina Romanova, is dedicated to “the process of returning our ethnic code.”16 It involves burying the restless spirit with which they fell in love or going back to the childhood they didn’t know, initiating a chain of self-transformations in search of a lost identity. “Are we able to go through the ritual?” asks the narrator’s voice in Orto Doidu (The Middle World, 1993).17

Orto Doidu, an encyclopedia of traditional Sakha life, is perhaps the most important and ambitious of Romanov’s films. During filming, he and Ekaterina used Yakut names, Uot Ayarkhan and Keremen Sata, which were included in the credits as a “sign of the ‘return’ of our ethnic identity,” consistent with Sakha cinema’s claiming of its own “voice.”18 The Sakhafilm company was established to produce the film, with Romanov as its artistic director, and a logo showing “a shamanic drum as the ‘voice’ of our ancestors, and on it is an image of a winged horse with an anthropomorphic muzzle, a symbol of the creative principle.”19

It is clear that “voice” is central to the function of Sakha cinema as self-identification. But the question, once again, is: Whose voice? The aforementioned films amplify the canonical writers of Soviet-Yakut culture; the same goes for The Shaman’s Dream (2002), which is based on an epic poem by Aleksey Kulakovskii (1877–1926)20. Written in 1910, the poem tells of a shaman who becomes an eagle and sees apocalyptic visions: the world drowning in imperialist wars and revolutions, and finally, the existence of Yakuts threatened by more powerful and technologically advanced nations, such as China, the United States, and Germany. The shaman concludes that the Sakha people, as a “small nation,” should not isolate themselves but rather adopt the learning and technologies of other nations to survive.

The “voice” in question is mediated and proceeds along a chain. Sakha identity and tradition speak through ancestors, who speak through the classics of Soviet-Yakut art and culture, who in turn speak through the films of Alexei Romanov/Uot Ayarkhan to the present generation. The chain leads back to mythological prehistory and forward into a post-historical future.

Following Hanegraaff’s invitation to see the revival of esoteric beliefs as mirroring secular thought, we find ourselves today in a period in which reconnection with spiritual traditions reflects secular trends in identity politics, decolonization, and decoloniality. Oppressed national identities and forgotten folk traditions speak with the voice of the spirits. By giving voice to those spirits, we might understand Sakha cinema as a séance—a special technique for the invocation of spirits.

The Childhood We Didn’t Know

I read the “non-Western” spiritual beliefs of Sakha through the lens of “Western” esotericism because I propose that their reinvention is part of a shared late–New Age historical moment. For many people today, esotericism serves as a broad alternative to both empirical science as a hegemonic worldview and the dominant world religions, as well as a way to escape modern imperialism, colonialism, and oppression. Knowledge that resists these tendencies is found not only in non-Western traditions, but also in “pre-modern” Western traditions.21

These traditions—which are now being recovered and renewed—have many more commonalities than differences. The trend towards their rediscovery, reinvention, and representation in contemporary art shares with New Age spiritualities “a manifestation of popular culture criticism, defining itself primarily by its opposition to the values of the ‘old’ culture.”22 So it is no surprise that many—if not all—of the protagonists of this esoteric revival come from a secular, modernized culture that they later rejected. In this respect Alexey and Ekaterina Romanov, who came out of the educated Soviet-Yakut cultural elite and sought the voice of a lost tradition within themselves, are exemplary.23

In my view, the spiritual leanings of the late New Age should be considered as a “reflexive” or “second modernization.” That is to say, they are a creative (self-)destruction of industrial modernization: not so much a turn away from modernity as “a radicalization of modernity, which breaks up the premises and contours of industrial society and opens paths to another modernity.24 Reflexive modernization tries to recuperate what was lost in the transition away from traditional ways of living, without itself seeking a comparable rupture. In this way, reflexive modernization in art and culture dialectically overcomes and radicalizes both modernism and postmodernism by “linking tradition and modernity in a non-ironic way.”25 Works of art that give voice to oppressed traditions through engagement with local identities and spiritualities thus embody a new stage of modernization and should be considered progressive, albeit requiring a revision in our understanding of what progress looks like.26

The contemporary phenomenon of “global esotericism” is a reflection of this reflexive modernization.27 It critiques prevailing popular culture by insisting that spirits manifest in the various languages, traditions, and identities oppressed by modernity, capitalism, and colonialism. The traditions represented by these spirits share a nonexploitative and non-anthropocentric worldview of cosmic unity.28 Or at least this is how they are generally perceived and presented in the global centers of contemporary art, while for many of the “genuine” bearers and (re)inventors of these traditions, the spirits with whom they communicate are “only” that of particular dead person, and not representative of a culture or worldview. It is the combination of these rituals and practices with the radical strains of secular thought that has fueled their rise in contemporary art and culture.

In conclusion: each time we interpret the voice in a séance as representative of a tradition oppressed by modernity, we are playing into this process. We are seeing global esotericism as a mirror of liberatory thought and emancipatory theory, which serves this new stage of reflexive modernization. And this ongoing process in art and culture is emancipatory and creative, a function of what Wilson Harries called the “unfinished genesis of imagination.”29

Last year, Alexei Romanov released a sequel to Maappa. In Khaar Kyjaar Nomokhtoro (The Legends of Eternal Snow), we discover that Yld’aa was too scared to bury Maappa’s body and ran away. Many years later, under another name, he comes back to Maappa’s home as the head of a group of men who forcibly abduct an Evenki girl, who will be married to a rich Yakut knyaz (ruler) against her will.30 To save the girl, who is in love with someone else, and to fulfill his old vow, Yld’aa stays with Maappa. According to Romanov, it is a story of fidelity to one’s word and to love.

Sitting in the airport on the way back from the Bishkek International Film Festival, where Khaar Kyjaar Nomokhtoro debuted, Alexei Romanov was reading the poetry of Omar Khayyam when he suddenly understood what the film was about. He found his film mirrored in a Russian translation of a collection of Persian poems, first anthologized by a European orientalist who attributed them to a great medieval astronomer. This moment of global esotericism illustrates how one culture can be reflected and refracted by another. Khaar Kyjaar Nomokhtoro starts with these verses:

There are no heads where a secret would not mature,

The heart lives by feeling, hiding nothing.

Every tribe goes its own way …

But love is a hurricane on the paths of being!31

-

“Séance” in this text refers to a setting where there is contact with spirits during a special procedure, be it a spiritualist session or shamanic ritual. ↩

-

I use “esotericism” as a general category that includes occultism, spiritualism, and New Age religions, among other traditions. ↩

-

Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism (State University of New York Press, 1994), 88. ↩

-

Wouter Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought (E. J. Brill, 1996), 441. ↩

-

Hanegraaff, New Age Religion, 439. ↩

-

Piers Vitebsky analyzed this situation in terms of negotiations between the local and global: “It is no longer possible to make a watertight distinction between ‘traditional’ shamanistic societies … and the new wave of neo-shamanist societies … The shamanic revival is now reappearing in the present of some of these remote tribes—only now these are neither remote nor tribal.” Piers Vitebsky, “From Cosmology to Environmentalism: Shamanism as Local Knowledge in a Global Setting,” in Counterworks: Managing the Diversity of Knowledge, ed. Richard Fardon (Routledge, 1995), 188. ↩

-

“Sakha” is the name for the region used by the Yakut people who live there, while “Yakut” is an exonym coined by Tungus people, borrowed by Russians, and used for a long period. The official name of the territory since 1991 has been “The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia).” ↩

-

Vladimir Kocharian, Iakutskoe kino. Put’ samoopredeleniia (Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2024), chap. 9, EPUB. All translations from Russian are my own. ↩

-

Maappa (Sakhafilm, 1986) →. Alexei Romanov would later take the name “Uot Ayarkhan” to reflect his Yakutian heritage. ↩

-

Alexei Romanov, “Rekonstruiruia poteriannoe proshloe,” in Iakutskoe kino, chap. 1. ↩

-

Eva Ivanilova, “Uzhas belogo lista: istoriia iakutskogo khorrora,” Iskusstvo Kino, December 27, 2019 available link. ↩

-

Ivanilova, “Uzhas belogo lista.” ↩

-

Iakutskoe kino, chap. 3. ↩

-

Iakutskoe kino, chap. 12. ↩

-

Iakutskoe kino, chap. 12. ↩

-

Iakutskoe kino, chap. 14. ↩

-

Orto Doidu (The Middle World) (Sakhafilm, 1993) available link. ↩

-

Ekaterina Romanova, “TSvet snega: Severnost’ i kinoiazyk kholodnoi zemli (landshaft i prostranstvo smyslov),” in Iakutskoe Kino, chap. 36. ↩

-

Romanova, “Tsvet snega.” ↩

-

Uraankhaĭ sakhalar. 2 Fil’m. Son shamana (The Shaman’s Dream) (Sakhafilm, 2002) available link. ↩

-

See for example The Invention of Sacred Tradition, ed. James R. Lewis and Olav Hammer (Cambridge University Press, 2007). ↩

-

Hanegraaff, New Age Religion, 331. ↩

-

Although Vitebsky’s argument is different, it fits this model perfectly: “A rhetorical emphasis on Sakha ethnic wisdom fits in well with the pragmatic move towards a localization of political authority and of control over economic resources … The Sakha share certain features with the New Age movement in the West.” Vitebsky, “From Cosmology to Environmentalism,” 195. ↩

-

Ulrich Beck, “The Reinvention of Politics,” in Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, ed. Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, and Scott Lash (Stanford University Press, 1994), 3. ↩

-

Harry Lehmann, “Die Kunst Der Reflexiven Moderne,” in Orientierungen: Wege Im Pluralismus Der Gegenwartsmusik (Schott, 2007), 36. Translation mine. ↩

-

This second modernization often looks ambiguous when viewed from different geographical perspectives. Applying the lens of a second modernism to the Russian context, Maria Engström discerns “imperial pop-art or imper-art.” Maria Engström, “Neo-Cosmism, Empire, and Contemporary Russian Art: Aleksei Belyaev-Gintovt,” in Russian Aviation, Space Flight and Visual Culture, ed. Helena Goscilo and Vladimir Strukov (Routledge, 2017). ↩

-

Today scholars try to “transcend the confines of Western esotericism” as an analytical concept and a scholarly field, proposing instead global perspectives, such as the program of global religious history, which regards esotericism as a globally entangled subject. See for example Julian Strube, “Towards the Study of Esotericism without the ‘Western’: Esotericism from the Perspective of a Global Religious History,” in New Approaches to the Study of Esotericism, ed. Julian Strube and Egil Asprem (Brill, 2021) available link. ↩

-

Talking about Western neo-shamanism, Kocku von Stuckrad notes the prominent role of the concept of nature and of the holistic feeling of connectedness to it: “Each neo-shamanic workshop can be considered a council of all beings.” Kocku von Stuckrad, “Reenchanting Nature: Modern Western Shamanism and Nineteenth-Century Thought,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 70, no. 4 (2002): 780. ↩

-

Wilson Harris, Selected Essays of Wilson Harris: The Unfinished Genesis of the Imagination, ed. Andrew Bundy (Routledge, 2007). ↩

-

The Evenki people, formerly the Tungus people, are an Indigenous Tungusic group of Eastern Siberia, living today in China, Russia, and Mongolia. In Russia, the majority of Evenki live in the Sakha Republic. ↩

-

Literal translation by the author from the Russian version of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, quoted in the film. ↩

The English version of this essay is also available in e-flux journal #156, a special issue for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Séance: Technology of the Spirit.

Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/156/6776751/who-speaks-during-a-s-ance

This essay is originally commissioned for the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Catalogue, Séance: Technology of the Spirit (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2025), scheduled for publication on October, 2025. With the author’s consent, it is being published in advance on the Seoul Mediacity Biennale website and e-flux Journal. No part of this essay may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.

© 2025 the author, copyright holders, Seoul Museum of Art and Mediabus, Seoul.