Dedicated Person

This interview is a conversation with Yekyung Kil, an editorial member of the 9th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, about the Biennale, editing, publishing, and content. It includes an edited transcript of the voice recording, related image materials, and the interviewee’s biography.

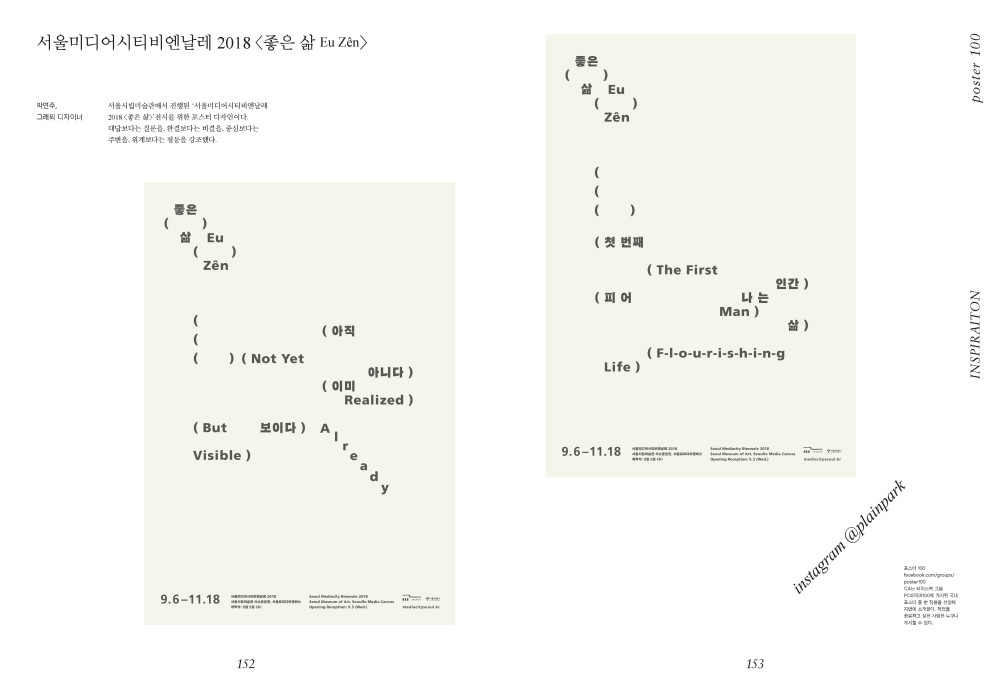

Yekyung Kil is an independent art publishing editor and translator based in Seoul and Jeju. After studying experimental art, she worked as a guest reporter for several art and design media publications. In 2016, Kil served as co-editor of the catalogue and chief editor of COULD BE published by Seoul Museum of Art for the SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016 NERIRI KIRURU HARARA. In 2022, she participated in the forum 2022 SeMA PITCHING: Art Museum that Archives, Remembering Future (SeMA Art Archives) and co-translated Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age by Kenneth Goldsmith (Workroom Press, 2023). She is currently proofreading a book about social and political posters.

Research Title Dedicated Person

Category Interview

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Participants Yekyung Kil, Seoul Mediacity Biennale Office

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

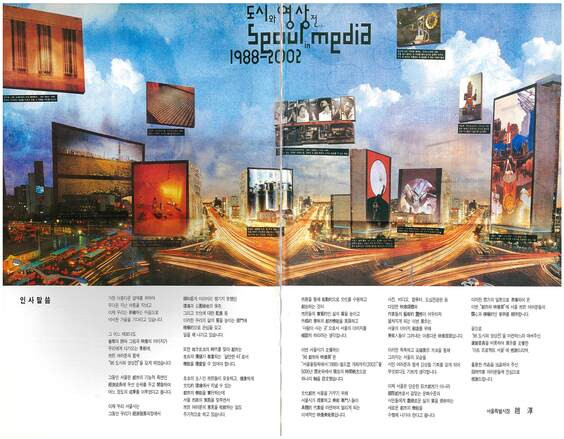

In 2022, Seoul Mediacity Biennale (SMB) established a dedicated research team tasked with examining the identity of the Biennale. Edited by this team, Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996–2022 Report (Seoul Museum of Art, 2022) compiles data from the Biennale’s 27 years of history, starting with the 1st SEOUL in MEDIA held in 1996 and running through the 12th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale held in 2022. In doing so, this publication discerns the transformations in the Biennale’s structure and operations, covering the history of the Biennale’s evolution in conjunction with changes in the domestic and international art scenes. The report divides the Biennale’s history into five phases: “Creation of Identity” (1996–1999), “Creation of Form” (2000–2006), “Trajectories” (2008–2012), “SeMA (Seoul Museum of Art) and Biennale” (2013–2018) and “Media Art” (2019–2022). It also distinguishes the structural changes that transformed the Biennale during each phase as well as the implementation of new roles and increases in expertise, which are examined in interviews covering topics of curating/research (Lee Sop), science/technology (Wohn Kwangyun), artist/media (Yangachi), museum director/executive (Kim Hong-hee) and media/records (Kim Kyoung-ho, Hong Cheolki). These are included as primary resources that facilitate understanding of the Biennale’s complex evolution, as interpreted through personal experience.

The 13th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale, which includes programs taking place throughout 2024, upholds the objectives of the previous pre-Biennale program in 2022 and presents new contents that explore conceptual research on media, the identity of the Biennale and regional connectivity. The following interview is an extension of the previous interview series and focuses on the Biennale experience over the past 10 years by presenting the perspectives of experts who have charted new paths amid the changing contemporary art scene. The 9th Biennale (2016) was marked by remarkable growth and meaningful achievements, particularly in terms of its comprehensive and diverse publications and programs. This interview with Yekyung Kil, an editorial board member of the 9th edition, discusses the role of the Biennale’s editorial projects and the complexity of content production in print media, before ending the interview with her words for future Biennales.

SMB Let’s begin with your background and motivation for participating in the 9th Biennale in 2016. You studied art and started your career in art publishing due to your interest in art resources, printed matter, archives, and speech and writing. In 2014, you took charge of the archive and library at the 4th Anyang Public Art Project (APAP)—did you have any prior experience in art publications?

Yekyung Kil (KIL) I got into art publishing at a time when English began to appear more regularly in exhibition catalogues and art publications in Korea. At first, I did a lot of English translation and proofreading, but I gradually took on other editing jobs. Usually when translating an original Korean text into English, there are cases where footnotes are necessary in English but not in Korean. Just like exhibitions and artworks, texts that cannot be understood without the help of additional explanations/footnotes appeared in publications, and therefore the scope of my editing commissions expanded into writing footnotes and commentaries on Korean manuscripts translated into English.

I guess my connection to the Biennale came about through people I had previously worked with in the fields of editing and publishing, who then went on to work with SMB. I previously served as an editorial member for the journal Bol,1 published by Insa Art Space, and I already knew Park Chan-Kyong, artistic director of the 8th Biennale (2014) by then. I joined Professor Sohyun Park on the catalogue editorial meeting for Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers – Modernities against Modernity edited by Ku Helen Jungyeon when I was invited to recommend contributors for the catalogue. Likewise, during a project in which the journal Bol was invited to participate in documenta 12 (2007) and the 7th Gwangju Biennale (2008), I worked on several publications with Beck Jee-sook, who became the artistic director of the 9th Biennale, and we spent a lot of time talking about media and editing. As an extension of these collaborations and conversations, I was invited to participate in the 9th Biennale as a member of the editorial board.

There is a lot that I would like to share about the 4th APAP, but I’m still contemplating the best format for discussing my experiences. The editorial and publishing work that I have observed and learned in Korea always resulted from an unspoken process in which like-minded people gathered and formed ideas naturally before establishing any fixed guidelines or procedures. Some overseas experts say that the Korean art world in the early 2000s was more interesting because of its variability, which was intrinsic to the stage of development prior to a fully-formed system. So far, I’m also enjoying the open possibilities of this process, like finding a “constellation.” I started out thinking that a blog might be an appropriate format for me to organize and document these experiences like Gerrie van Noord, an editor who runs her own blog and serves as an important reference for my documentation. While working at APAP, I did not have enough time to record the process personally. Although the general term for my work is “editing,” I have taken on slightly different roles such as proofreading, copyediting, researching and inviting contributors, etc. Someday, I would like to create an “annotated chronology” of the various publications that I have worked on and examine their relationships.

SMB Good place to open up this conversation is the 9th Biennale’s Open Editorial Meeting, a publication conference that inagurated the pre-Biennale program held in 2015. At the time, you explained how you came to think of art publications as an independent medium and tool capable of expanding the impact of temporary events like biennales, which are held once every two years. This may have been the first time in the history of the Biennale that discussions about art publications were held in a public setting. How did this idea come about and what can you share about the overall creative process, including the Open Editorial Meeting between the four editorial board members and a graphic designer as a part of the pre-Biennale program?

KIL Yumi Kang, the assistant curator of the 9th Biennale, knows a lot about this topic, so I recently contacted her by phone to ask her about it. She said that it was planned by artistic director Beck Jee-sook and assistant curator Lee Jiwon. After the Biennale exhibition team made their decision to make the meeting public, Kang contacted the four editorial board members and a designer—Keiko Sei, Chimurenga (Ntone Edjabe), Miguel A. López, Moon Jung Jang and myself—and we proceeded to hold the related events and work toward our objectives. When it comes to the backstory, the first thing that comes to mind is the title COULD BE.2 At the internal planning meeting for the Open Editorial Meeting, opinions were expressed that we ought to give individual titles to the publication’s four issues. I suggested COULD BE—which I had heard several times in a conversation between visual culture researcher Wonhwa Yoon and an artist at the art space Audio Visual Pavilion—and the exhibition team concurred that this phrase was frequently used by other artists/designers. As far as I could tell, the other editorial board members agreed to adopt COULD BE as a title because it originated from artists.

SMB Not only are the contents of the first Open Editorial Meeting summarized in the Biennale catalogue (pp. 358–367), but they were also documented in the form of video recordings. At the time, you assumed the role of moderator and mainly asked questions, while the other editors told stories that touched on subtopics of “future,” “knowledge” and “language.” These three topics demonstrate the correlation between “biennale” and “art publishing,” even though they obviously exist as distinct mediums: biennales are temporary and thus subject to time constraints, while art publications can be re-read in the future and used for different purposes in subsequent eras. Although they share the same objective of communication and sharing, they reflect key differences in terms of their language and methodology. During the meeting, there must have been concerns about keeping COULD BE as an independent publishing project while also remaining relevant to the Biennale. Can you elaborate on the three keywords that were presented at the meeting?

KIL The question about connecting art publications and biennales is related to the time and space in which readers and audiences live. The reader may or may not be the audience and the audience may or may not be the reader, and it is impossible to know what language is being used. For example, I have never visited documenta or Sculpture Projects Münster, but I have read the texts that they produce and publish as pre-programs. I actively purchase their catalogues, read them at the library or view them on exhibition websites, and I also typically read magazine articles written by people who have visited the exhibitions in person in Europe. I heard that documenta also assembles a separate art publishing team for each issue, and I know that the founder and director of Sculpture Projects Münster was Kasper König, an art publisher who created art books with several conceptual artists, so I get excited whenever I read art publications about Sculpture Projects Münster that are held every ten years. Biennale publications sometimes lead to books, too: I’ve recently been reading a book by a sociologist, and it turns out that the author was inspired by a program at documenta. Not long ago, the Korean translation of the book Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World by Timothy Morton came out. As our readers would know, a chapter from that book had been previously first introduced in Korea as an essay contribution to the catalogue for the 9th Biennale. Although I was unable to attend the summer camp The Village (curated by Yang Ah Ham) held during that edition of the Biennale, I was still able to find out what the attendees discussed thanks to the program’s corresponding publication (Everyone’s School: The Village Project, mediabus, 2016).

Here I would like to invoke the words of science fiction writer William Gibson:

“The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”

I mentioned this quote at the Open Editorial Meeting 1, and it was also used as the title of the 2016 Sydney Biennale (led by artistic director Stephanie Rosenthal). Gibson doesn’t recall when or where he originally made this statement, but he has speculated that it arose in a conversation with his friends and later became well-known after he repeated it in several interviews. According to the introduction to the 2016 Sydney Biennale from the website of its host institution (Museum of Contemporary Art Australia), the exhibition was organized to reflect on the “now” as well as the information gap. I also strive to discover and understand how artists approach knowledge production (discourse) and storytelling (narrative) in their work, as well as how they present new practices by traversing these two methodologies. The language of art can attract audiences or drive them away. As such, various experimental writings may be able to cater to readers in other aspects by adding to existing criticism.

SMB Let’s move on to discuss how the subsequent editions of the Open Editorial Meeting were held and made public. What do you remember about the other meetings, which were not recorded separately?

KIL I heard from Yumi Kang that after the first meeting there were plans to hold two additional sessions of the Open Editorial Meeting with the five editorial committee members: once after each issue was published and once during the Biennale. However, there were difficulties since the members were located in different time zones, so the additional sessions were held as Open Editorial Meeting 2 (Keiko Sei, Yoon Hyangro and Parit Chiwarak) and Open Editorial Meeting 3 (Liz Park, Miguel A. López and myself). Photos of the events and the discussion topics are also summarized in the 9th Biennale catalogue. All these meetings were held in the Project Gallery on the third floor of the Seoul Museum of Art, which is a relatively small space, for an audience of around 20 people who were notified via announcement.

I brought and introduced the publications of documenta and Sculpture Projects Münster as related resources for Open Editorial Meeting 3, even though they weren’t primary source materials for the 9th Biennale. These publications were released before the events took place. The journal of documenta 14 was created in collaboration with South (an abbreviation of South as a State of Mind), a semi-annual journal of arts and culture published in Athens which I discovered thanks to The Book Society, whose second bookshop was located at SeMA. Electronic booklets titled Out of Body and Out of Time published by Sculpture Projects Münster in 2017 were also printed on several paper copies.

SMB It seems that the types of stories exchanged at those meetings are still very relevant today. Things like disasters and uncertainty continue to endanger our lives, although art provides us with an open platform through which we can speak about the future. Another topic discussed at Open Editorial Meeting 1 was the need for a space that would allow for free speech as well as the use of various languages, and during the Q&A with the audience you handed the microphone to curator Heejin Kim, who at that time was developing a few projects related to the Sewol Ferry Disaster. The process of examining contemporary social issues, common memories and collective traumas can be said to be an important role of the Biennale in the sense of media practice. In that regard, what do you think differentiated the 9th Biennale from other international cultural events or special exhibitions held around the same time?

KIL From the day of the Sewol Ferry Disaster in 2014—and especially after the alleged “rescue of all people” was revealed to be a false report—the majority of Korean arts and culture professionals reduced or halted their activities. A year later, in 2015, the exhibition team announced their detailed decisions regarding preparations for the 9th Biennale: selected artists and artworks, titles assigned to the Biennale exhibition team staff, the Biennale’s identity and its scheduled exhibitions, performances, publications, conversations, workshops, etc. This is a difficult question to answer because the ways in which artworks displayed at the Biennale move the heart, change the mind and lead to action are fundamentally different from person to person. The same must have been true for the organizers of the Biennale and its participants alike, even if many visitors only connected with a small number of works or experienced a few workshops.

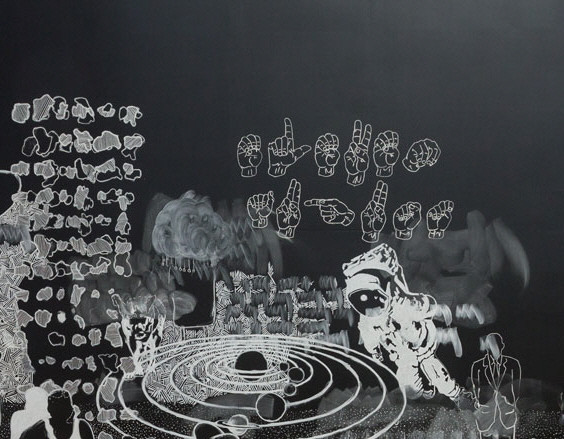

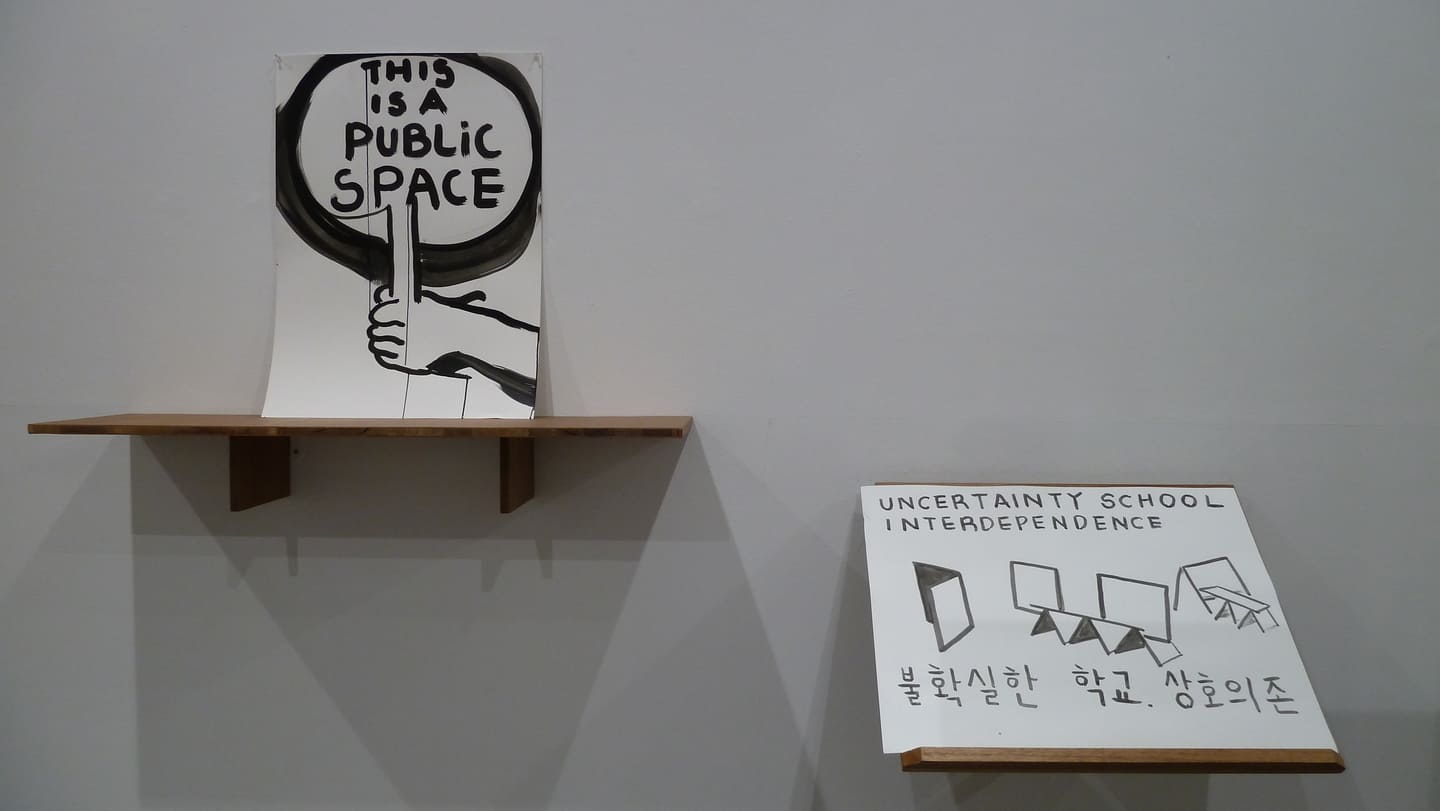

As an artist and citizen, I value the obvious fact that SMB is supported by the Seoul Metropolitan Government and that SeMA is a cornerstone of the city’s cultural infrastructure. Interdependence, an exhibition curated by Uncertainty School participant Taeyoon Choi, was a clear success when it was held at the Buk-SeMA, the biggest satellite branch of SeMA. I think we also achieved a milestone when Christine Sun Kim won the 2016 SeMA-Hana Media Art Award (conferred jointly with Korakrit Arunanondchai). Since then, whenever I think or say the words “deaf,” “normality,” “disability” or “non-disability,” my heart starts pounding. As I was reading the 9th Biennale catalogue, I noticed that the meaning of media practice you mentioned was discussed in A Dialogue on NERIRI KIRURU HARARA (Beck Jee-sook, Keiko Sei and Jung-Yeon Ma). I recommend that everyone read and re-read it for themselves.

SMB The publication COULD BE No. 1: Trios of Guides elaborates on the state of arts in Korea at the time as well as contemporary issues relevant to daily life in a changing era. Could this collaborative writing project and public exchange of individual knowledge have been inspired by the methods adopted vis-à-vis Open Editorial Meeting? Rather than revealing any clearly defined topic, COULD BE No. 1 freely unfolds ambiguous yet realistic stories about art in Seoul between 2015 and 2016. What can you share about the editorial intention behind this publication?

KIL When we started planning COULD BE No. 1, we decided to invite Wonhwa Yoon and curator Seewon Hyun as writers and have them hold a writing class. I remember there were four people at the first meeting, including Yumi Kang, who was the assistant curator in charge of publications for the 9th Biennale. We talked about various methods of collaborative writing, such as experimental approaches of writing together in one location or writing one sentence or paragraph one after another. In the end, we each wrote our own pieces and collected free writings without a clear theme. The topics of COULD BE No. 1 were “walking” and “collaborative writing.” (We are currently working on a book with two contributors from COULD BE No. 1 at the SeMA Art Archives).

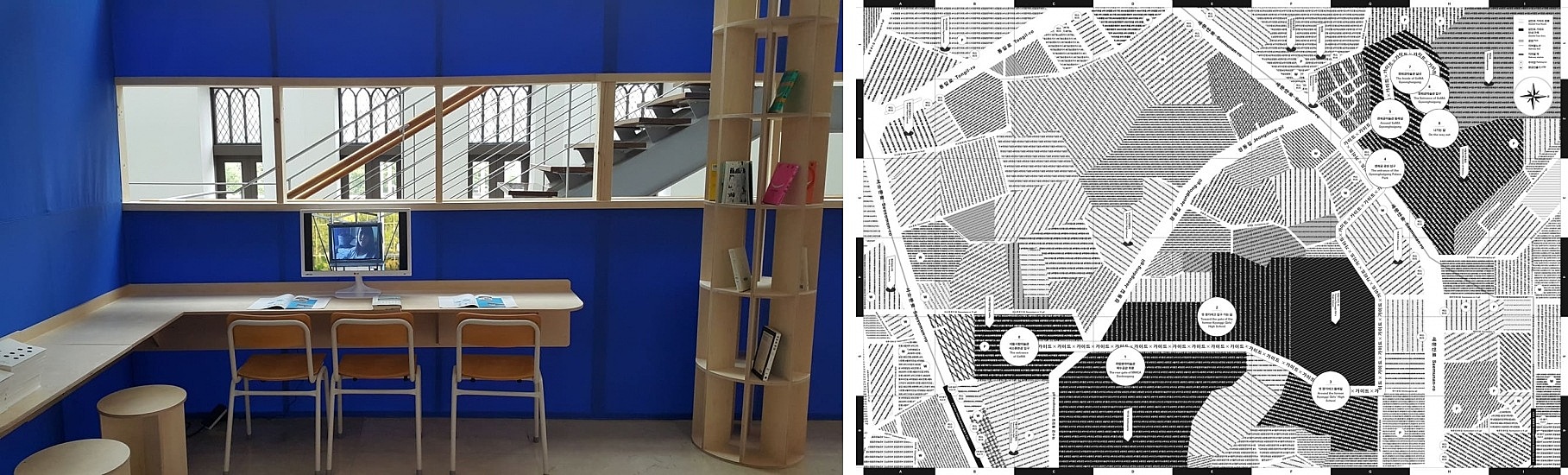

KIL It is said that when people talk while walking, their manner of speaking and their actual language undergo changes. There have been cultural and artistic projects that adopt the methodology of psychogeography, such as detouring or drifting in urban space,3 which we expanded from walking and writing to map-making. Our work began with a walk around the SeMA Seosomun Main Branch building, a program titled Guide to Guide. Among the participants of this walk were quite a few people who had never met before. Wonhwa Yoon, who led Guide to Guide, did not want the event to be filmed on video and I agreed that such a recording of a temporary writing production meeting seemed unnatural. The only documentation that I have consists of a few photos that were taken before and during the walk itself. Various photos of the interior of the Seoul 600Year Memorial Hall, which were included in the Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996–2022 Report, were taken by one of the participating writers. Today, several other branches of SeMA are operating throughout the city, which itself is so large that it is impossible to walk around its entire circumference. What we tried to do in that program was only possible, not to mention meaningful, because it took place at that particular moment in time. Thinking back on how the project was centered around a writing preparation group that formed teams and “walked,” I realize that we could have selected the topic and controlled the project’s progress as its “chief editor.” After all, sometimes the most interesting writing comes from working within constraints. However, I thought that such methods were better left to experts in their own fields, whether they be writers, editors or curators. Rather than giving direction and leadership, I decided to let participants work together freely. As I recall, SeMA attempted to mount an exhibition at that time presenting various “new art spaces” that had recently opened, but there was a sense of resistance or suspicion regarding institutions like SeMA bringing attention and opportunities too quickly to very recently initiated practices with specific names. In other words, there were concerns about true “participation.” From my perspective, collaborations are like temporary performances. While walking during Guide to Guide, I think I had more open-minded conversations than might have been possible while sitting in an office environment, where they might have felt quite awkward. I thought that “walking” was suitable for voluntary participation related to emerging art movements like “new art spaces.” Essentially, that project contained nothing more than the distance that we walked and the time that it took. Even if I don’t discuss the lack of a clear theme, it ought to have been conveyed through the book itself, right? So a reading area for COULD BE was set up inside the Biennale exhibition hall to allow the publication to serve as a means of talking unto itself—but more than that, it explains the context behind the publication so that the full story of the project can be understood.

SMB COULD BE was published as four separate issues, each different in its format, content and design. At first glance, the editorial team members for each issue seem to have nothing in common—aside from their respective editing experience—due to their distinct backgrounds, activities, personalities and interests. It is also difficult to imagine a common denominator for the four issues aside from their title COULD BE, Biennale credits and a brief announcement of the next issue. How did you go about differentiating each issue while also maintaining continuity throughout the entire project?

KIL Keiko Sei, Chimurenga (Ntone Edjabe) and I (through journal Bol) previously participated in the documenta 12 Magazines Project (2007). Keiko Sei worked as an editor at documenta 12 Magazine and as a regional coordinator for the documenta 12 Magazines Project. In preparation for this interview, I found out that Miguel A. López, who was invited to edit COULD BE NO. 4 Radical Anticipation, used his blog to introduce several journals that participated in the magazine project.4 Artistic director Beck Jee-sook said that she initially wanted to produce COULD BE in a newspaper flyer format. In fact, this approach had already been adopted by various biennales and organizations, and there was also precedent for a publication’s format alone serving to make a statement. Chimurenga, who was invited to edit Chimurenga CHRONIC / COULD BE NO. 3 The Corpse Exhibition and Older Graphic Stories, had also produced publications in the form of newspapers, and although I don’t remember exactly, Beck Jee-sook probably thought of the newspaper format after meeting Chimurenga, who was introduced at Performa 15 during the exhibition team’s preliminary research stage.

Each issue of COULD BE was conceived with a different publication format and paper design. What might have happened if the artistic director had dictated these parameters? I believe that every detailed choice in publication production—such as the selection of colors and data according to a hierarchy or importance of their content, or considerations of the audience and what design tools to use—are all political decisions of the designer. That is why I think designers are personally responsible for almost half of a given publication. Any book’s design is informed by everything its designer has done in the past and suggests what they plan to do in the future. I think a designer’s intention is important in determining the form of the publication. For COULD BE issues 1-4, Moon Jung Jang was invited as the designer. In the case of Chimurenga CHRONIC / COULD BE NO. 3 The Corpse Exhibition and Older Graphic Stories, Chimurenga had been planning a special issue as an extension of the existing Pan-African quarterly magazine Chronic, which meant that its format could not be changed and their respective in-house designer would have to design it themselves. Therefore, Chimurenga’s publication was designed in a newspaper format, and although the other issues could have adhered to the same format, they were ultimately designed differently. The artistic director proposed various topics, but there was no way to predict how ideas would change and emerge during the process, especially in terms of the texts that the invited writers would submit. Therefore, the design was determined through the process of developing ideas and reading the texts.

SMB You also organized a joint event that invited the public to read the script of Guide to Guide, which was not published in print. What do you recall about that event?

KIL At the end of the intro to COULD BE No. 1, I wrote that I would “prepare a space for the Guide to Guide Script” and created a separate reading space in the exhibition hall. Yumi Kang oversaw the buildout for that space.The script of Guide to Guide was beautifully installed, with each page connected like the scroll manuscript of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and Guide to Guide itself was distributed in the form of a map. Curator Liz Park, whom I met at Open Editorial Meeting 3, was impressed by this map and told me that the audience ought to reenact the walking program for themselves.

SMB Looking at the Biennale catalogues that have been published so far—although it is difficult to confirm accurate information—those produced for the early editions of the Biennale served different purposes. This changed during the 6th Biennale (2010), which took a more professional approach to publishing, and continued to evolve during the 8th Biennale (2014), which produced an independent publication in the form of an anthology that examined various topics in depth. For the 9th Biennale, we sought to incorporate publishing into the Biennale structure as a concept that permeated the entire Biennale. That’s why, in addition to the editorial board members, there was an assistant curator in charge of publishing within the Biennale’s team. For the 12th Biennale last year, the SMB Newsletter was published on a monthly basis beginning in the pre-Biennale year and the role of the catalogue was separated into a guidebook and anthology.

Recently, people seem to believe that exhibition catalogues focusing solely on exhibition information and archival photos are conventional and meaningless. However, it cannot be denied that such documentation is necessary, at a bare minimum. What are your thoughts on the role of editing in the field of art publishing? Traditionally, exhibition catalogues were produced for the purpose of exhibition criticism, while today the subjects carrying out criticism and the media through which such ideas are delivered have become diversified, not to mention the means of appreciating and experiencing exhibitions. In a situation where the exhibition format itself is undergoing transformations, questions inevitably arise as to whether art publications are absolutely essential for exhibitions. What are your thoughts about this?

KIL There are many artworks, especially in the field of conceptual art, that exist only in art publications and are not presented in physical exhibitions. Conversely, there can also be exhibitions without publications. Art publishing frequently invokes digital publishing and democratic digital culture for a variety of reasons, with progressive media activists claiming that there is no need for physical archives at all. On the other hand, although the internet is an important platform, there are also arguments for reducing digital reading and writing. That is why there is a new focus on paper publications as a growing trend. In the end, readers are important, but publications may not be necessary, depending on the audience. In cases where the composition of the exhibition or artwork is difficult to express in the form of a publication, I think holding an exhibition without an accompanying publication is certainly reasonable. Alternatively, experiential exhibitions wherein the flow of visitors is controlled and the results are predetermined may not require art publications. I fundamentally believe, however, that exhibition publications are a medium capable of broadening our understanding and bringing us one step closer to the artwork. Moreover, we cannot overlook the fact that when it comes to visual creation and production—including typography, editorial design and printing—publications also shed light on the designers who were active in Korea at the time and the ideas and concerns that interested them.

SMB You also contributed as one of the editors to the 9th Biennale catalogue. Since the catalogue constitutes a comprehensive result of the entire Biennale, it must have required a great deal of teamwork among all collaborators. In fact, there were 14 contributors and five editors, including you. Were there specific roles assigned within the role of “editor” on this project? And do you feel that the final result corresponded to what was originally intended?

More generally speaking, do you think the role of an editor is necessary in exhibition planning, and if so, how would you explain it? Just looking at the Biennale records, in the early years tasks such as editing and commissioning were shared among the Biennale’s Organizational Board and moved to the artistic director of each edition, but now they tend to work with external publishers and editors, while the role of the editor has become more and more specialized. Recent trends indicate that publishing and editing are increasingly considered the domain of experts. Can you talk about the Biennale’s reasoning for recruiting professional editors or a devoted publication expert?

KIL First of all, I think it is important to define the term “editing” itself. I always define my own role for each publication I work on and I believe in the necessity of developing more accurate editing-related terminology. If you look closely at the role of “editing,” specific names are given according to each distinct task such as project editor, managing editor and commissioning editor. I recommend analyzing the nomenclature and editorial roles compiled by Gerrie van Noord, an art publishing editor and researcher working with curator Paul O’Neil and writer Lucy Steeds. At the 9th Biennale, I partially served as commissioning editor of planning/manuscript,5 since I invited the contributors for Could Be No. 1 as well as the catalogue.

I’d like first to think about those who are considered to be experts in art—before thinking the same in publishing—, typically defined as people who majored in art history or graduated from a curatorial studies department. I don’t consider myself an expert, but I think that I belong to the last generation to play such a role. When I started working, there was no detailed system in place, so I would like to say that I am a “dedicated person” rather than a “professional.” I used to be a reporter for an art magazine, and as I worked as a freelance translator and an editor, I embraced my role as a reporter to deliver effectively while also gaining a lot of experience by taking on responsibilities that expanded from contacting writers to making layouts. At the time, I once had to do my own design (as an experiment), so I also learned the basics of “editorial design” using book design tools.

Within the art system, each director or artistic director considers publications to be important, yet their degree of importance varies. I think that for biennales, the editor’s role lies somewhere between that of the chief editor (artistic director) and the designer. In fact, many of the publications for the 9th Biennale reflect the designer’s decisions. The results generated from the artistic director’s original concept are bound to differ from the initial proposals, and in our case the differences were huge. I think this is the advantage of big events like a biennale, where numerous ideas are considered through a natural process before reaching the final result envisioned by the artistic director. I think it was good that the 9th Biennale had an assistant curator within the team dedicated to publications. Creating an appropriate space for people to work together was the method employed by the artistic director at the time, both at art institutions as well as large biennale-type exhibitions. I don’t necessarily think you need to bring an expert into that position. The term “dedicated person” may be an arbitrary interpretation on my part. So, whenever I feel that I am suitable for a position that is offered to me, I join the project. The objectives that I achieved at the Biennale were recently covered in a research paper and analyzed theoretically. I’m interested in finding out what happens when you create a network—I believe that people who talk theoretically and verbalize things like that are experts. I hope to read more of their theories on art publishing. And I think that there ought to be an official event in order to more accurately review the Biennale’s publications. On the other hand, we must be wary of falling into fixed patterns as such increased specialization. I think it is the role of the Biennale team to specialize while remaining flexible. To sum up, the role of an editor can be seen as that of a cultural activist who deals with intellectual history or, in the words of Keiko Sei, “searches for a language for analysis and thinking.” In my case, I often support such people, whether overtly or behind the scenes. Some people keenly observe where and how the intellect moves or introduce other areas such as philosophy, sociology and literature that are tangential to art, and talk about this flow. I think those things are what ultimately determine the success of the art publication.

Ultimately, a successful project can only be achieved with sufficient time, effort and workforce. These may vary depending on the characteristics and decisions of the art director, but I would like to emphasize that dedicated/professional personnel are necessary. I would also like to mention editorial thinking—just like the joke that says “art absorbs everything,” many projects are currently being produced in contemporary art through interdisciplinary collaborations. I think it’s an art publishing editor’s job to watch how things coalesce and disseminate throughout various fields and I’m very interested in this kind of thing. Whenever art takes nourishment from other disciplines such as philosophy, aesthetics, sociology, anthropology or archeology and translates them into works of art, artists must know and learn about different fields. Now, more than ever, I think we need an editorial approach and mode of editorial thinking that seeks to understand, integrate and rearrange experience and knowledge across multiple fields in art, especially since we are collaborating with external fields from the outset and raising common questions.

SMB There’s also the topic of publishing formats and how they have changed. At the last Biennale, there were many attempts at this, including a catalogue, anthology, guidebook, postcards, newsletters and web publications. How would you describe the relationship between biennales and art publishing and what do you think the future of this relationship should look like?

KIL Every biennale has its own unique character and identity. And I think that Seoul Mediacity Biennale, as its name implies, has no choice but to address prevailing concerns and fundamental changes in cities, art and media itself. This will always be different whether they are presented through an exhibition or through a program or publication, but I think the question of identifying the Biennale’s audience should always be considered and the working approach adjusted accordingly. It is impressive that publications are now produced on an ongoing basis rather than existing merely as temporary gestures, such as the Sydney Biennale’s publications for children and teenagers or the Tate’s Teachers Pack. Examples like these come to mind when examining the relationship between biennales and publications. It’s important for everything to be available together rather than having to look for things separately.

Thank you for inviting me for this interview. I hope you will consider our conversation as secondary material that supports the historical evidence of art exhibitions. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Yumi Kang, who found valuable information in emails and external hard drives and helped me greatly in confirming the facts while we both exclaimed, “Why is it so hard to remember all this?”

Interview Date: February 16, 2024

-

Bol, a quarterly critical journal of visual art published by Insa Art Space of the Arts Council Korea, put out 10 issues from 2005 to 2008; Insa Art Space also published a special issue No. 11 in celebration of its 20th anniversary in 2020. Bol is housed in the collections of various art institutions such as Arko Archive and SeMA Art Archives (Reference Library). ↩

-

COULD BE was a periodical comprising four issues that were released intermittently, focusing on topics suggested by the editorial board members at the Open Editorial Meeting. It is available for download on the Biennale’s website. ↩

-

Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking, trans. Lee Jae-hyung (Seoul: Chaeksesang, 2014). The original French text was published in 2009 and the book was introduced in an email sent to contributors on March 1, 2006. ↩

-

Miguel A. López's blog, accessed on May 1, 2024. ↩

-

Kim Hak-won, What is an Editor? revised edition [digital version], Humanist, 2021. ↩