Media Art = Publicness

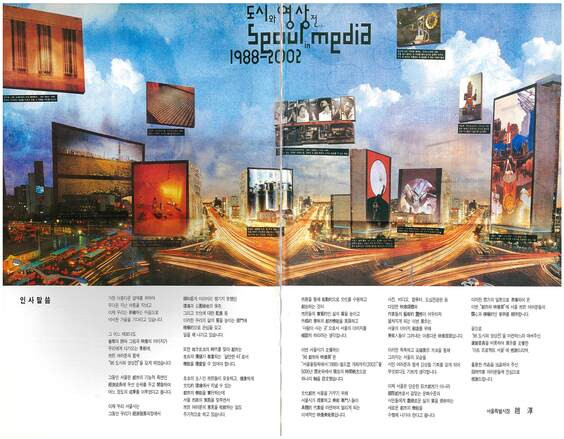

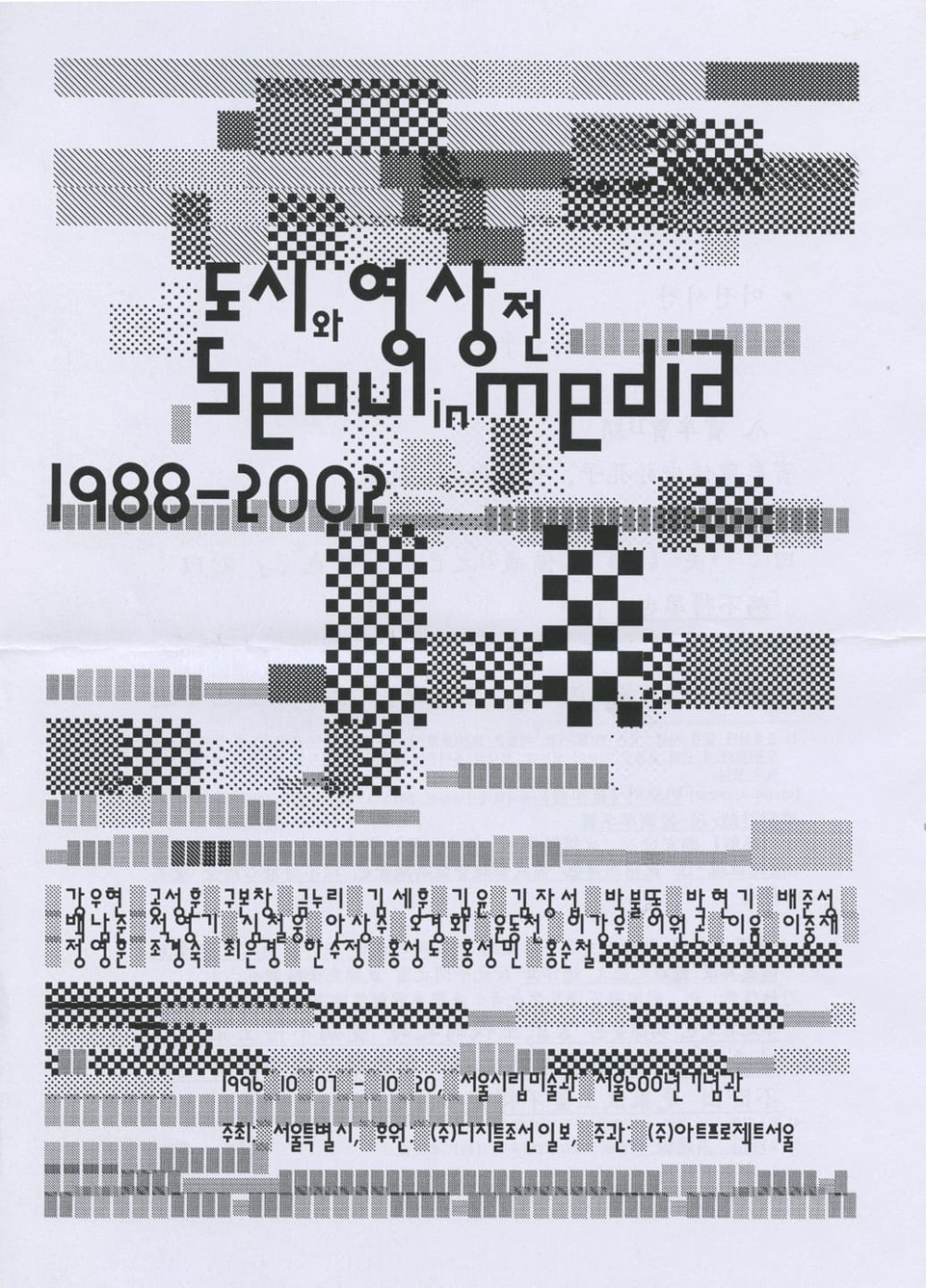

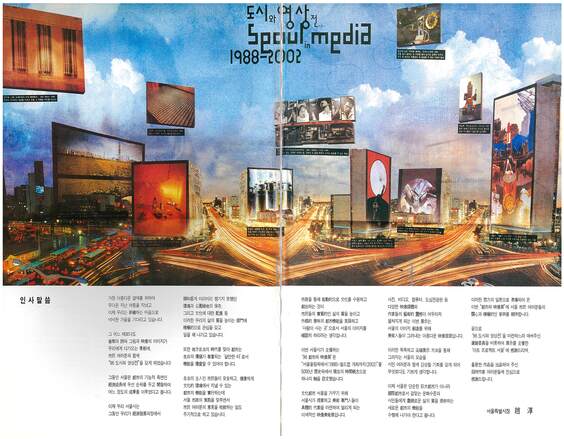

This interview is a conversation with curator Lee Sop about public art and biennales. It is a re-edited version of the interview from the Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996-2022 Report, published in 2022, with the addition of relevant images in 2024.

Lee Sop was the curator of the 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002. After mounting his debut solo exhibition Lee Sop Exhibition in 1984, he served as exhibition director at Namu Gallery, Art Consulting Seoul (ACS) and Ilju Art House. He is primarily concerned with the institutionalization of “public art” as the universal goal of all art practice and has realized various projects that forge links between art and society as well as art and daily life. He was a researcher and director of Writing, Choi Min (Yeolhwadang, 2022), a publication focused on the archive of art critic and poet Choi Min, as well as Cheerful Learning, Delightful Knowledge, Joyful Knowing (2023), the inaugural exhibition held at Art Archives, Seoul Museum of Art.

Research Title Media Art = Publicness

Category Interview

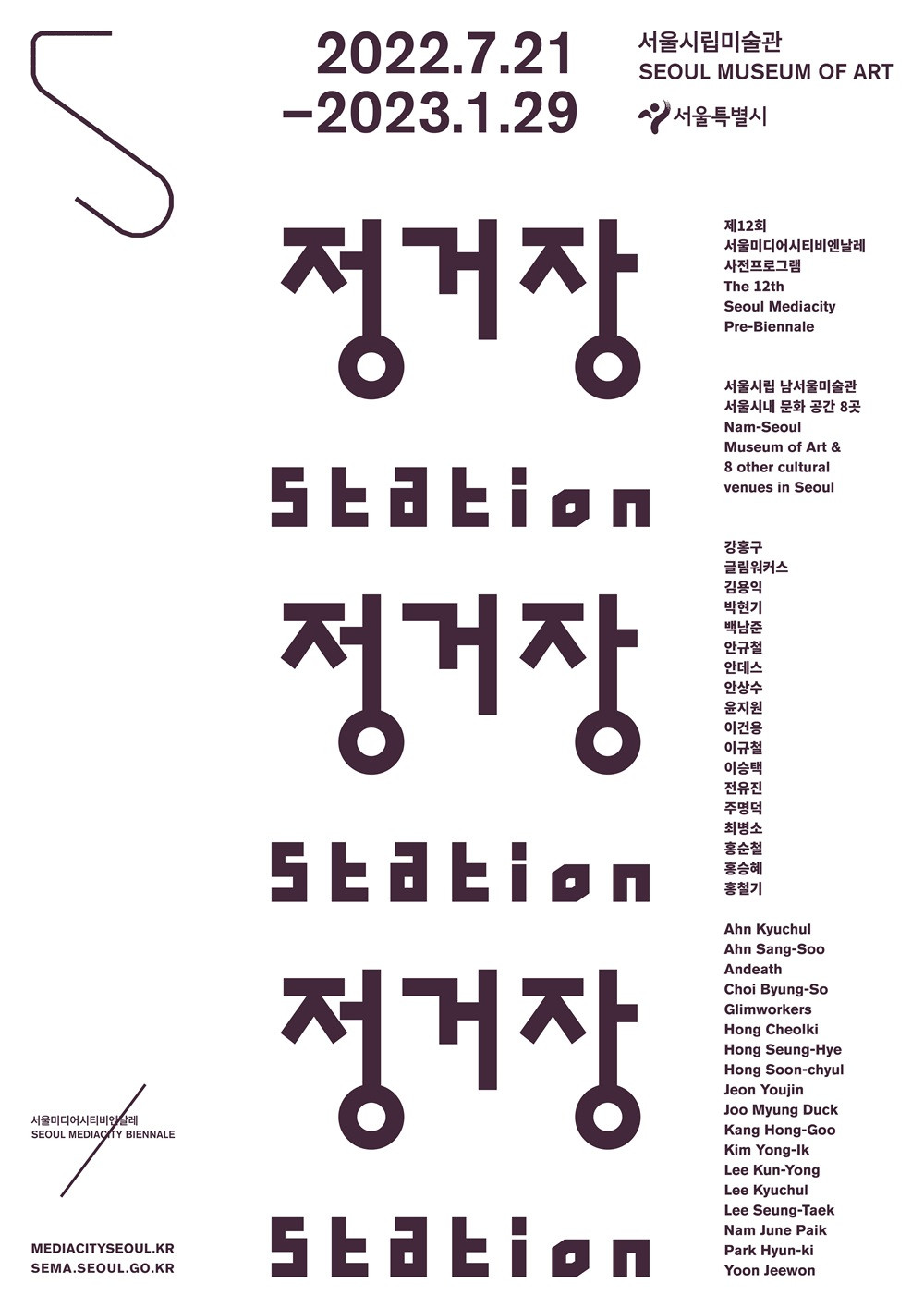

Edition The 12th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Participants Lee Sop, Seoul Mediacity Biennale Office

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

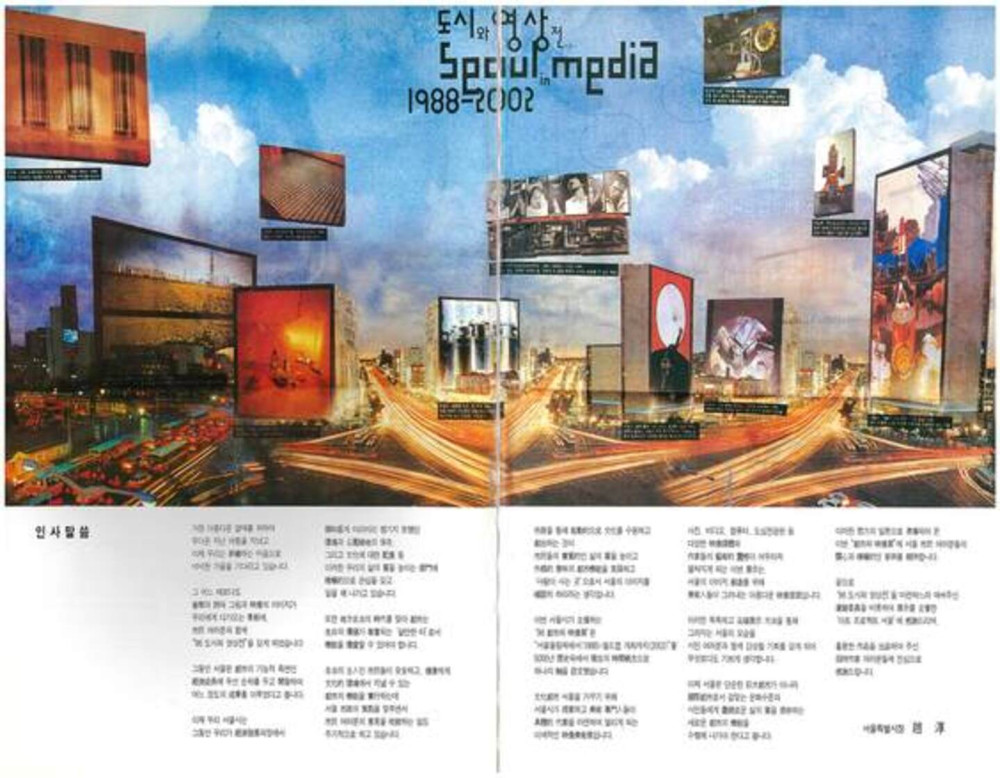

SMB Hello. Thank you for your time today. The Biennale completed its eleventh edition in 2021. The Biennale was inaugurated in 2000, but another exhibition is often regarded the forerunner of the Biennale, the SEOUL in MEDIA, which held three times beginning in 1996. Unfortunately, there is little available information about what this particular exhibition looked like. To start off, can you explain your role in organizing SEOUL in MEDIA and what inspired the project?

LEE SOP (LEE) I can only tell you what I am able to recall from memory, since I myself have hardly any records of the project. I first heard about an exhibition called SEOUL in MEDIA being planned by the city of Seoul from Kim Hong-hee, who asked if we (Kim Jinha and Lee Sop) were interested in participating in a type of nomination process. After accepting the invitation and discussing further, we realized that she had already worked out a framework for conceptualizing and organizing SEOUL in MEDIA. In response, we suggested some realistic plans for the exhibition, many of which were implemented, which allowed things to progress naturally.

SMB Was it the SeMA that established the initial framework, or the organizing committee consisting of Kim Hong-hee, Park Hyunki, Ahn Sang- soo, Kang Junhyeok and Cho Duckhyun?

LEE As far as I recall, it was the committee. They combined the separate concepts of “Seoul” and “media,” and then we came up with some ideas to effectively realize the two concepts.

SMB The agency that took up those practical ideas was known as Art Project Seoul. Does that still exist?

LEE The company was called Art Project Seoul in its early years, although it later changed to Art Consulting Seoul. Preparations for creating the company began around 1996, but operations formally began in June or July of 1997. The 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988 – 2002 was our first project. The business ultimately closed down in December 2010.

SMB What was the purpose of creating that business?

LEE Public art. We actually called it “public arts.” We thought that the “art” in “public art” shouldn’t be limited to fine arts. I was running Namu Gallery with Kim Jinha at that time. Yi Joo Heon, a co-organizer of The 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988 – 2002 had just joined Hakgojae Gallery after quitting his job as an art journalist at The Hankyoreh while another co-organizer, Park Samcheol, was working hard as an art journalist at Sports Chosun.

I learned the concept of “public arts” while doing related research with Kim Jinha. We contemplated how to adapt the global trends in the art world to our setting by referencing foreign books and magazines such as Art in America. Park Samcheol and Yi Joo Heon shared our stance and joined the research, and we collectively came to the conclusion that public art represented the ultimate direction for art. At the time, many people in the art world went along with the “postmodern” wave, and there was a tendency to devalue art museums or galleries as mere “white cubes.” Today, however, there is more of a consensus. There are obvious limitations to art which exclusively seeks expert knowledge; it doesn’t help the artists and only ends up confining the audience or potential subject of enjoyment with certain walls. Add to that the trend of considering art collections as examples of elegant hobbies by people who break down those walls-we hated these things. Therefore, we out-rightly claimed to pursue public art. That’s why we didn’t feel any pressure when we were offered the opportunity to work on SEOUL in MEDIA.

SMB I see. Then it must have been a logical decision for you to showcase works on electronic billboards throughout the city.

LEE Of course. Despite our focus on making that idea a reality, the committee was still strongly pushing for a white cube type of exhibition. We said that we would take full responsibility for the exhibition, since that’s what we had to do anyway. The format of the nomination process involved some negotiation, so we accepted the committee’s opinion to some extent.

SMB What were your criteria in selecting the artists?

LEE It was a time when video artists weren’t making art with publicness in mind. Unfortunately, that still largely holds true. The definition of video art as a genre within the realm of fine art posed a problem because it didn’t consider the notion of publicness at all. We took this issue very seriously and decided to try various ways of presenting videos. As a result, we also adopted a more technical approach to addressing this issue.

SMB Could you be more specific about the ‘publicness’ that Art Consulting Seoul sought to achieve?

LEE I cannot sufficiently explain that topic in this interview, but to be brief, we oriented our efforts toward reaching a point where art activities would not diverge from everyday activities. For more than a decade, the activities and work of Art Consulting Seoul were always carried out with this goal in mind.

SMB The year 1996 would have been just before experiments with new media, including video, had reached full swing in the art world. What else do you remember about selecting artists and organizing works during that time?

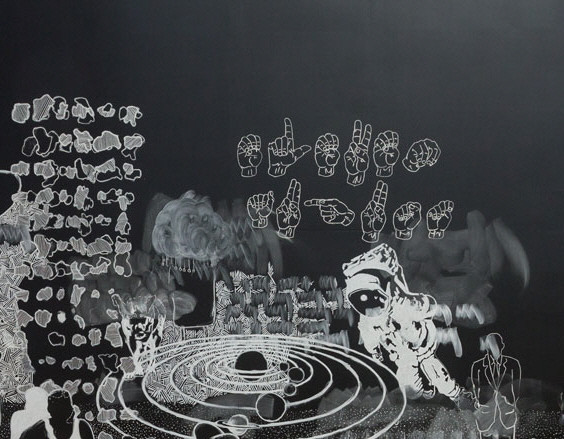

LEE One artist who realized the publicness of media art that we had envisioned is Hong Soon-chyul. He was a professor at Korea National University of Arts and a producer at a broadcasting company before than. Working with Hong was very meaningful. His piece containing scenes of toilets flushing was displayed at the Seoul Museum of Art (formerly the Seoul 600 Year Memorial Hall), while another piece shown on the electronic billboards was organized separately.

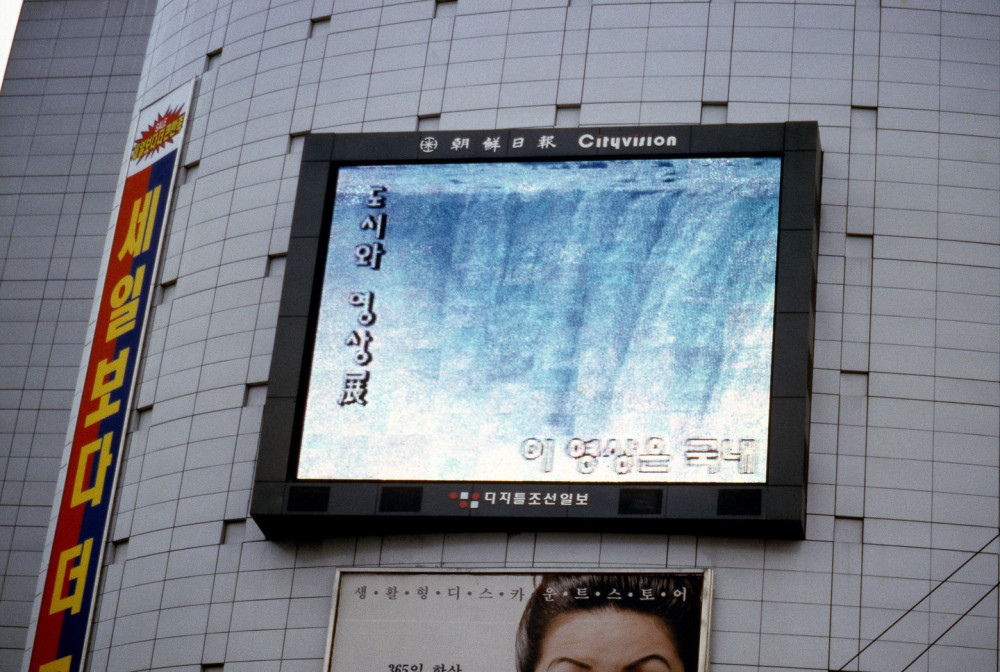

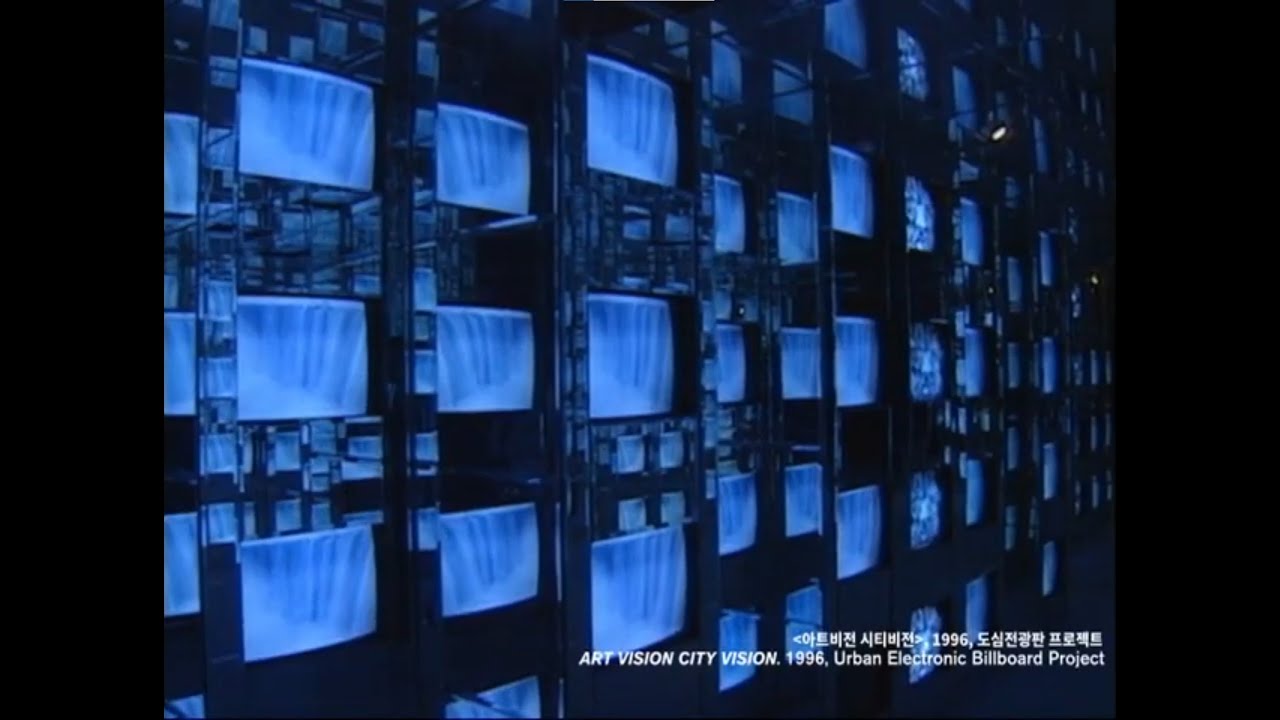

SMB Do you recall any specific challenges you encountered or other memorable moments from your time working on the electronic billboard project “Art Vision City Vision?”

LEE The billboards were operated according to particular specifications back then, so all videos had to be less than 90 seconds. We signed a contract to display one video work of that length once every two hours-or rather, the people who operated the billboards helped us to do so-and we edited the videos to fit the time constraints.

SMB Records reveal that ten artists participated in the “Art Vision City Vision.” Can we assume that the works of those ten artists were combined and edited down to less than 90 seconds, and that the same files were transmitted at multiple sites?

LEE There wasn’t electronic transmission back then. Each bill board had its own connected system and prepared tapes were played at scheduled times. It was similar to the way that a disc jockey places the record player’s pin on a vinyl record to play music.

SMB Were they operated 24 hours a day?

LEE No, not quite 24 hours, but probably until 1 am or 2 am. For the first couple of days, we actually watched to make sure they would play the works at the agreed times.

SMB According to the catalogue, there were billboards in Suwon, Bucheon, Incheon, and Busan, in addtion to those in Seoul.

LEE There were only fourteen billboards in Seoul at that time.

SMB So you used all the available billboards in Seoul?

LEE All except for one in Gangnam, I think. And we only checked places like Suwon or Bucheon once, so I’m not really sure if the videos were played as promised. (LAUGHS)

SMB How did you screen the works that appeared on information displays at banks?

LEE Banks had TVs for advertising that would feature their own ads-“Create this account,” etc.-or other messages regarding bank etiquette. The banks played the videos that we provided, in between their existing contents, every hour. From what I remember, they played the videos six or seven times per day, from 9 am to 4 pm.

SMB How was “Art Vision City Vision” received by the public?

LEE At the time, Roh Hyung Suk, who is still working at The Hankyoreh today, had just started working as an art journalist, and he showed a particular interest in this project. One time, we went out to the Gwanghwamun intersection together to see the billboards on the buildings of the Dong-A Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo, and Roh was asking questions to random people on the street. However, most people didn’t really notice the videos-or, at least, they didn’t realize that the videos were different than the regular advertisements that appeared on the billboards. They just thought of them as new advertisements and didn’t see them as “artworks.”

SMB It seems like there must have been a lot of technical difficulties or other issues with human resources related to the project. How did you handle such problems, and did you have any outside help?

LEE There were such large gaps in technology that the files created with the types of cameras used by the artists couldn’t even be displayed on large electronic billboards. Since the files couldn’t be played as is, they required a technical converting process of readjustment of colors. At first, we tried to solve this problem by looking for engineers who worked as videos editors at broadcasting companies. We managed to find a company that produced the various media sources for billboards, but they requested a very high fee that exceeded the budget of the exhibition. In the end, we talked to the technicians who worked on the sources for the Chosun Ilbo’s signboards and received help from their personal contacts.

SMB I guess the works played on the billboards had a natural connection with those at the museum exhibition, since the artists that participated in the exhibition also displayed videos on the billboards. “Art Vision City Vision” must have also entailed experiments and efforts in video art beyond the “new advertisements” you mentioned earlier.

LEE I do remember that it was laypeople, those waiting in line at the banks who had more interesting responses than experts. That said, they would have been more entertained if we had screened a soap opera rather than an artwork. (LAUGHS) Considering the movements of people on the street, 90 seconds is a fairly long time to pay attention to a particular billboard, so the question was whether or not the videos were worth stopping for and watching. I don’t think that was the case. Considering the potential impact of videos created as artworks compared to commercial images, I think that artworks have less appeal. It was obvious that people didn’t remember them, and the project ended as an interesting attempt on our part.

SMB Do you remember anything more about invited artworks including the City Waterfall by Hong Soon-chyul?

LEE I remember a scene from that piece in which a person positioned above the waterfall looks as if he is seeing the outside from within the screen.

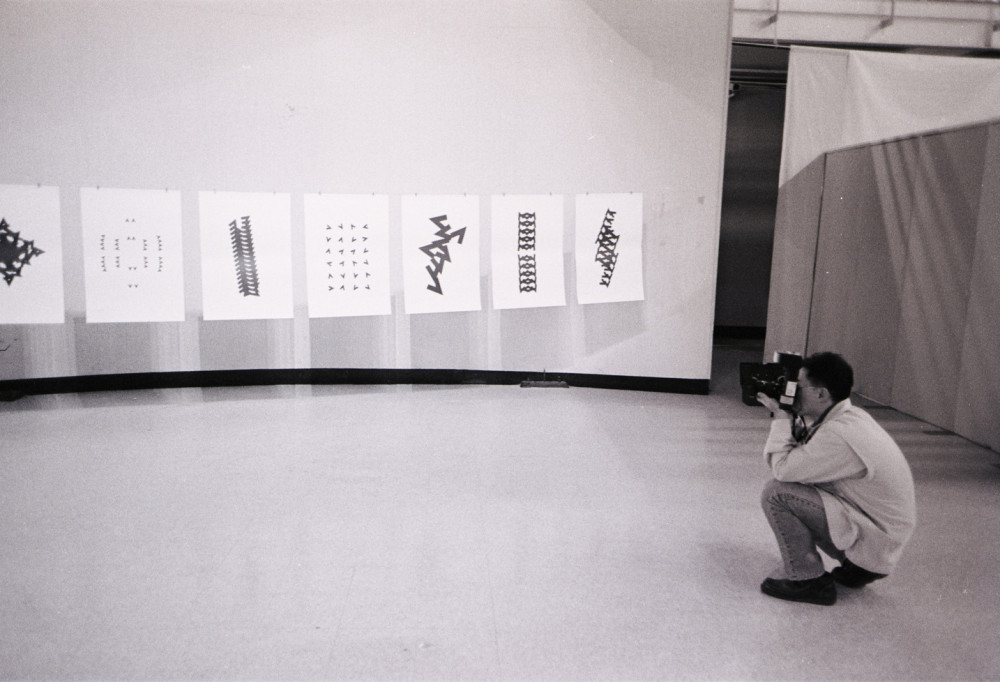

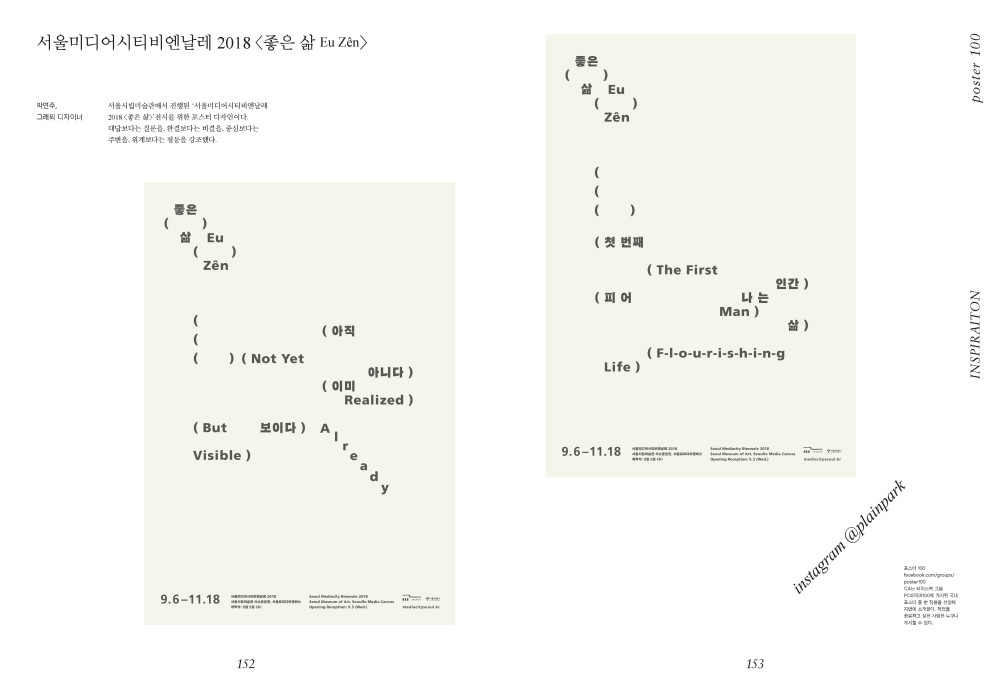

Another participating artist was Park Hyunki, who is one of Korea’s first- generation video artists. The reason we included him was to celebrate and promote the fact that Korea actually had a pioneering artist in media art, and that media art could be one of our representative art genres, too. Back then, we also had many discussions with Ahn Sang-soo, who was one of the committee members, about typography as media and he also submitted his works to the exhibition. Nam June Paik presented his works, too, which allowed us to connect historically memorable points, one after another.

SMB Did you encounter any technical difficulties in the museum exhibition?

LEE Since it was the first exhibition centered around media art, we didn’t have any technical specialists or specific procedures. Each artist had a different opinion as well as their own demands. The only way for us to proceed was by simple trying our best to meet their needs. In retrospect, the exhibition The 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988 – 2002 didn’t receive much positive feedback. Even now, I still think that we lacked a strong sense of subject matter internally; we understood contemporary trends but filed to exhibit contents that embodied those trends, and we weren’t able to recruit such artists. In a way, I felt ashamed because I may have regarded the project as a way of making money. When someone who creates exhibitions starts to think like that, it is quite painful. The project should have been meaningful to me, even if others disregarded it. That’s why Art Consulting Seoul’s second project became organizing and programming a joint studio for art productions at Iljoo Art House.

SMB I saw numbers of single-channel videos produced by Iljoo Art House among the early audiovisual materials stored in the Biennale archive. Those videos show the early experiments of artists who are still active today. I had no idea that those works derived from Art Consulting Seoul’s education and production programs, in the aftermath of SEOUL in MEDIA. Do you remember the total budget for the exhibition of SEOUL in MEDIA?

LEE It was about 70 to 80 billion won.

SMB To wrap things up, many people say that post-Covid-19 is a turning point. The Biennale has made various efforts with regard to media art over the years and is now taking this opportunity to collect and organize past materials, which has shared the cyclical nature of trends and recollections, rather than being completely new. What future directions do you think might lead the Biennale down more meaningful paths?

LEE For it is to be meaningful, we should not search for ideas as turning points, but rather find artists who wholeheartedly experience, embrace and reflect on such turning points. For instance, you might exhibit works by someone who has never been called an artist. Turning points in art are proven by artworks.

SMB Yes, I agree. I think that is important. If you would like to make a final comment about the Biennale, please do.

LEE There is one thing that I thought about when I read the questions you sent me.

The title is Seoul Mediacity Biennale. How much responsibility are we taking from that phrase? Furthermore, how can the meanings of “Seoul” be analyzed? Words like metropolis or cosmopolis also spring to mind – if Seoul does encapsulate those meanings, we also need to ask questions about “media city” and the associations that such a term connotes. Is Seoul a “media city”? It is important to allow space for self-reflection on how to become a “media city” in the future as well.

Moreover, can we reveal everything that progresses, regresses or stagnates during each biennial period, in the pursuit of our self-regard, as a media city? I hope that this phrase can encompass all these considerations.

Interview Date: February 7, 2022