The Art Museum and Asia

This interview is a conversation with Kim Hong-hee, SeMA General Director/SMB Curatorial advisory committee member, who has experienced biennales in various positions. It is a re-edited version of the interview from the Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996-2022 Report, published in 2022, with the addition of relevant images from 2024.

Kim Hong-hee, the fourth director of the Seoul Museum of Art (2012-2017), served as an operational advisory committee member for the 1st SEOUL in MEDIA (1996) and planning advisory committee member for media_city Seoul 2000. For the past 40 years, she has conducted extensive research as an art historian, critic and curator based on her deep affection for media art and feminist art. In 1998, she founded the alternative art space Ssamzie Space; in 2003, she was commissioner of the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale; in 2006, she was artistic director of the 6th Gwangju Biennale Fever Variations; and from 2006 to 2010 she served as director of the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art.

Research Title The Art Museum and Asia

Category Interview

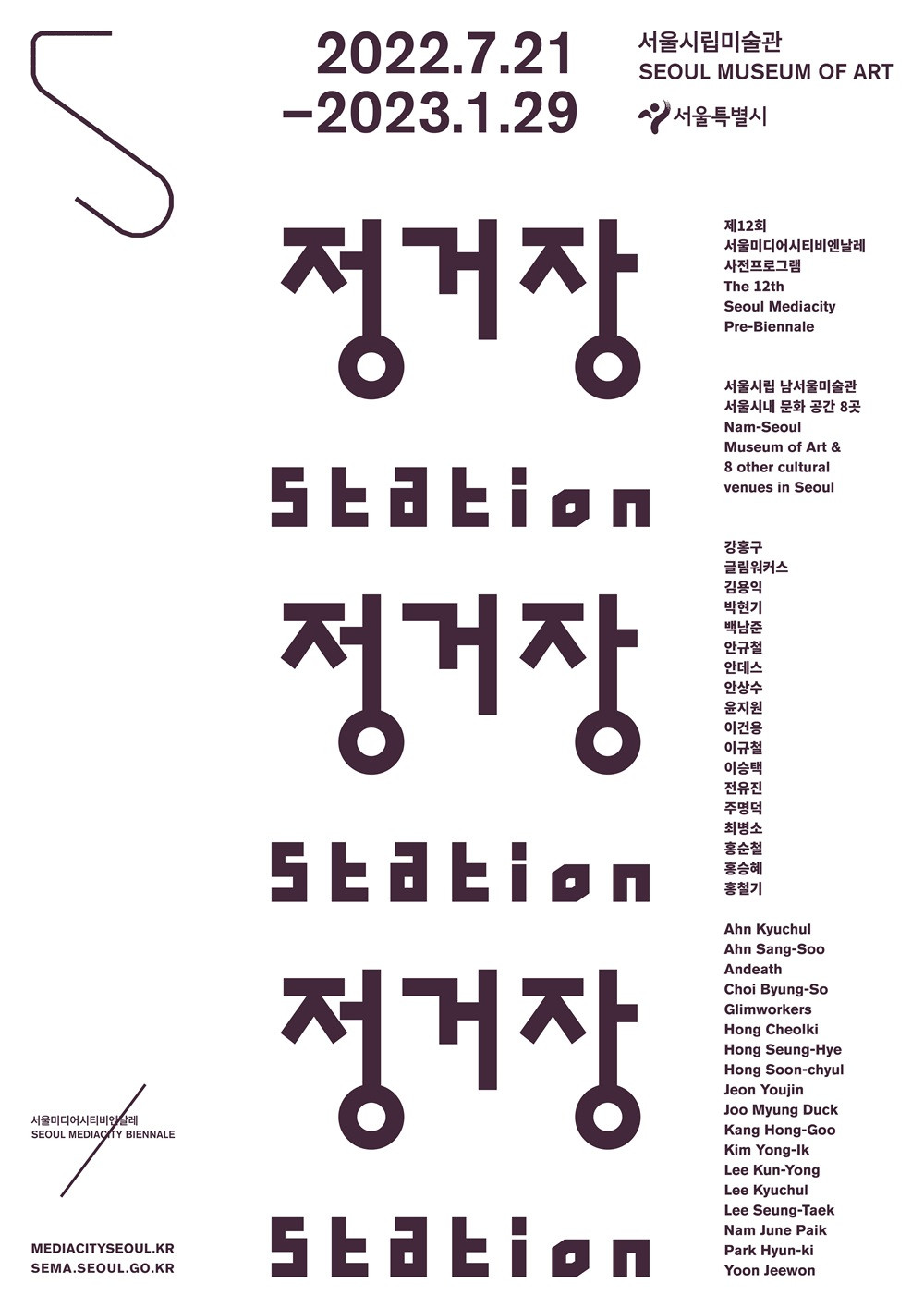

Edition The 12th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Participants Kim Hong-hee, Seoul Mediacity Biennale Office

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

SMB Since 2012, you have served as General Director of SeMA with the goal of creating a “curating culture” in the museum while the Biennale also underwent many changes during the same period. I would like to go back in time and discuss your initial involvement with the Biennale. You were a Member of Curatorial Advisory Committee at the media_city seoul 2000, and could you discuss your early experiences with it?

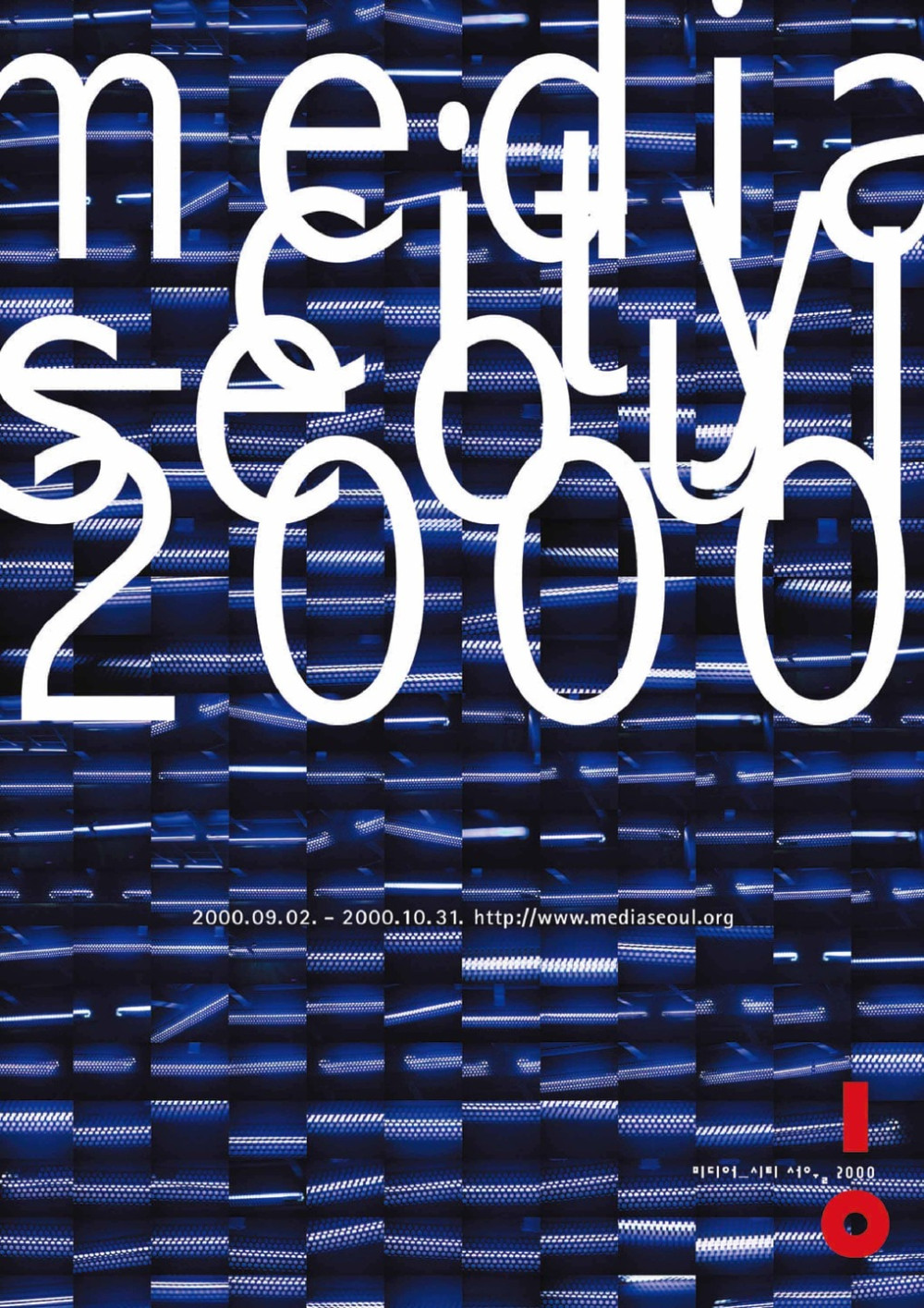

KIM HONG-HEE (KIM) In retrospect, that was an incredible starting point. As the first cultural event and art festival celebrating the new millennium, the inaugural Biennale in 2000 was organized with the goal of connecting Seoul as a media city to the world. I remember that it was distinctive in terms of the novelty value of asserting media as its central theme, while also attempting to recognize Seoul within the new perspective of a hub and medium of networks, and demonstrating the potential of media through art. There were many events aside from the exhibitions, most interesting of which was the “Triangle Workshop,” which as a certain three-way relationship connecting art, technology, and industry. To me, it seemed urgent at that time for the multimedia industry to embrace ideas from art and design because there was a clear need for artists’ creative ideas in order to forge a new cultural paradigm that went beyond simply offering technology. On the other hand, artists at that time were receiving far less technological support, compared to the present day. As an organizer, I searched for labs at corporations like Samsung or schools like KAIST that media artists could use, which wasn’t easy. However, the “Triangle Workshop” itself created infrastructure for supporting artists with technology, and that’s what made it so inspiring. In fact, the discussions that the workshop’s discussions triggered were extremely meaningful, as opposed to merely focusing on achieving certain results, and this allowed us to more fully address each other’s needs.

SMB Official documents show that there were 26 Members of Curatorial Advisory Committee for the Biennale in 2000. Even just glancing at the organizational chart allows us to imagine the scale of the event. What do you think enabled the event to operate at such a large-scale from the very outset?

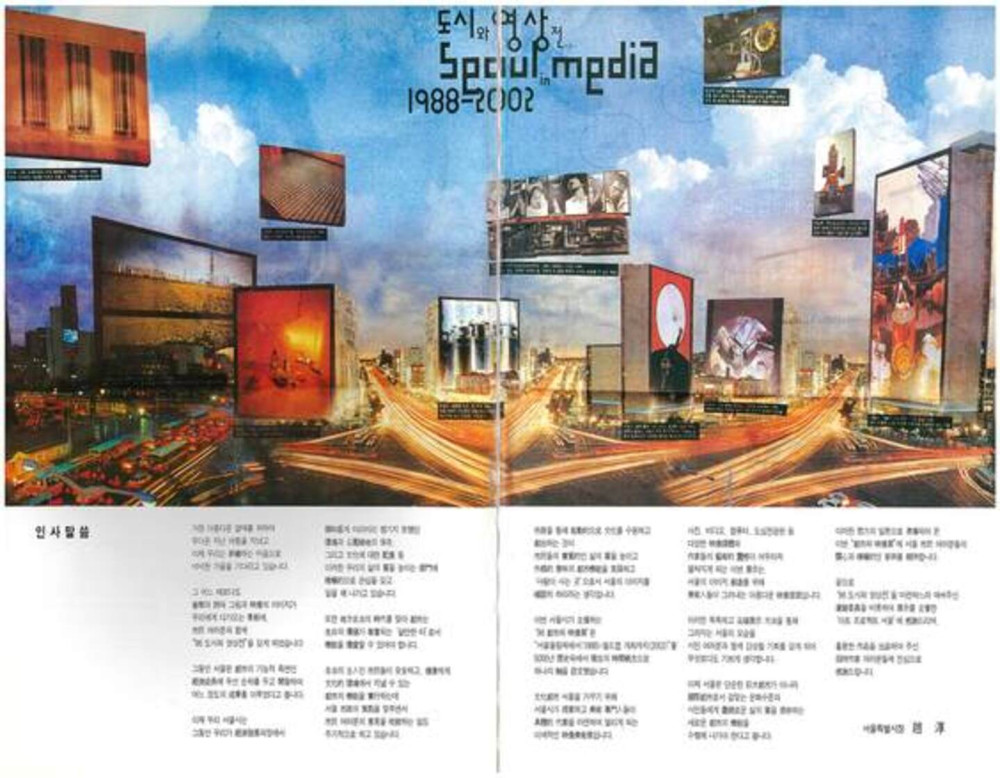

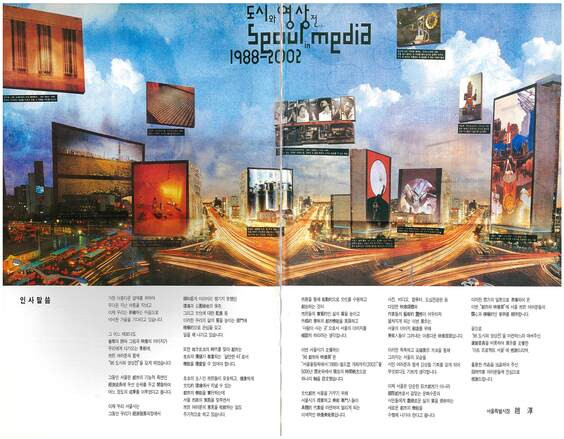

KIM The scope of the event was quite ambitious for a first-time project. The Biennale emcompassed “Digital Alice,” an interactive program for children; “Escape,” which introduced contemporary international artists such as Nam June Paik, Matthew Barney, and Bruce Nauman; and “City Vision/Clip City” a billboard project organized by Hans Ulrich Obrist that displayed short clips of famous artists’ works on electronic billboard around Seoul. Actually, we were criticized for using expensive billboards this way, (LAUGHS) although this response was somewhat unsurprising at that time due to a lack of awareness about media art among the general public. Additionally, “Subway Project: Public Furniture” took place in 13 subway stations in downtown Seoul. Undertaking such diverse ventures in all directions was only possible thanks to the media_city seoul 2000’s large budget. This was during Goh Kun’s tenure as Seoul Mayor, and he provided full-scale support for the event, while vice mayor Kang Hongbin also showed considerable interest and knowledge in culture. At the time, Song Misuk, the artistic director of the first edition, also established a foundation that provided the final push that allowed the event to succeed. Since the Biennale was organized by the city of Seoul, maximum manpower and budget were mobilized, although in subsequent editions the scale decreased significantly. This may be attributed to a decline in the government’s interest, but the art world should nonetheless reflect on the possible reasons for the city to reduce the Biennale’s scale.

SMB Compared with the inaugural edition of the Biennale, the budget for the second edition decreased tenfold. During the planning phase of the first event in 2000, it seems that discussions took place with regard to long- term perspectives. In addition to deciding to adopt the form of a “Biennial,” a vision for the long-term convergence of art, technology, and industry was also proposed.

KIM That’s right. We even ambitiously selected the place to hold the second edition, but in the end it fell through.

SMB Did the election of a new mayor influence any policy changes?

KIM That might have been a factor. Also, it’s easy to be disappointed whenever expectations aren’t set high enough. I think we experienced the side effects of trying to achieve all of our objectives at once, when we should have focused on making gradual progress instead. Regardless, given the deep budget reductions, I suppose that the city may have asked the question, “What are the outcomes, relative to the budget?”

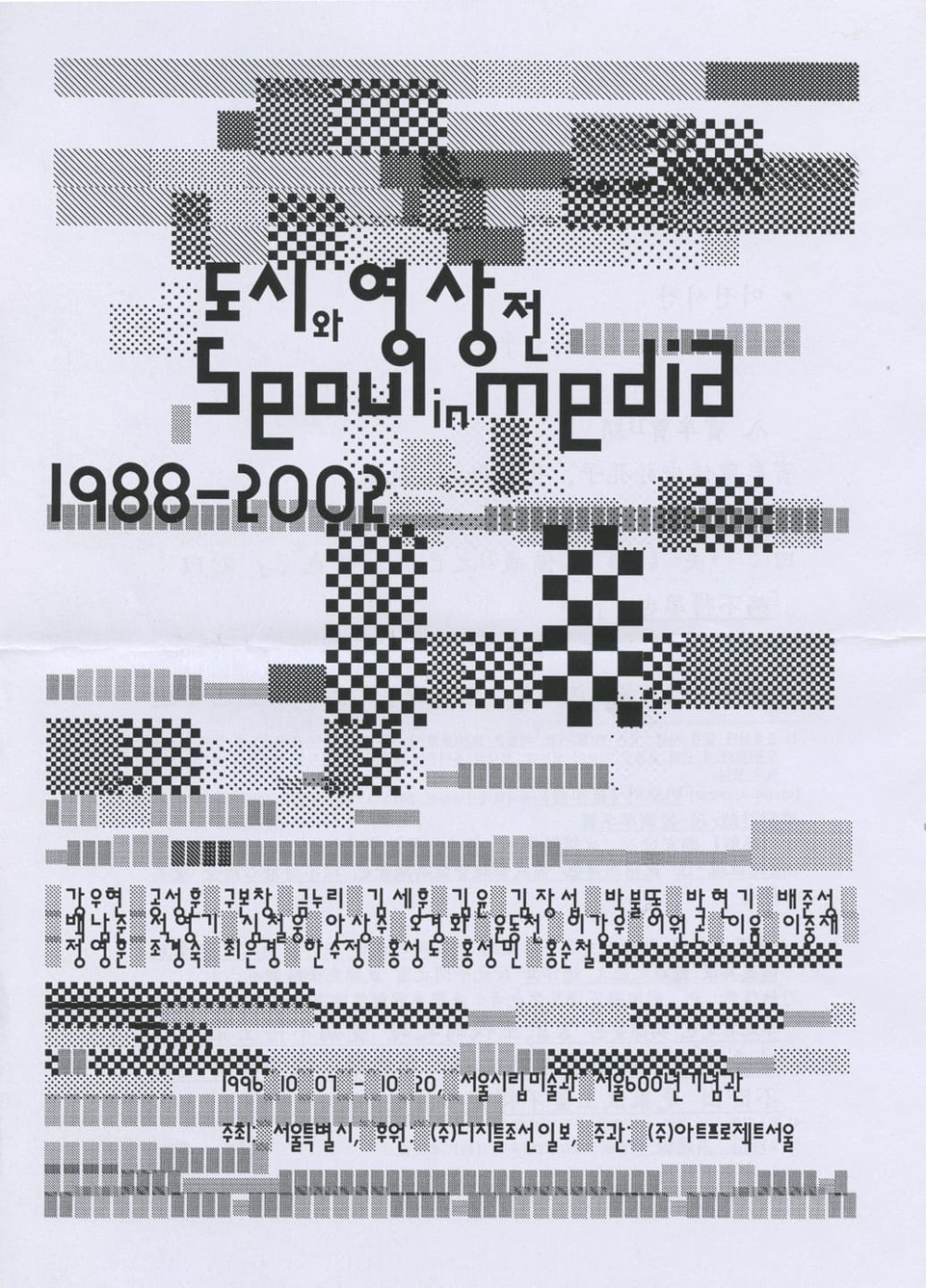

SMB Since you began your career in the Korean art world in the early 1990s, you have always focused on the new medium of “media.” As such, I think that you must have had an important role as a member of the Organizing Committee for the 1st SEOUL in MEDIA exhibition, the title of which made a strong statement. At the time, you were constantly involved in various events that focused not only on the interaction of the city and media, but also on changes that were taking place in the urban and media environments. Could you shed some light on the key factors that motivated you and your colleagues, you shared your vision of that era and organized events with you?

KIM From the mid-1990s to 2000, events like the Gwangju Biennale, the media_city seoul, and the Busan Biennale were initiated one after another and the Korean art scene was rapidly becoming globalized. Enterprising curators and artists tended to join forces as they participated in projects with great aspirations and expectations. However, in retrospect, I believe that there was a central force that was lacking, one that would have attracted and combined the passion for these individuals. One possible explanation for this is that government policy and strategy in the arts and culture sector were not yet established and were only implemented in stages. You might say that the energies of individuals was only able to spread sporadically. Although there were some people who possessed remarkable awareness, either the government support or the policies it implemented were insufficient to integrated and develop all this energy. This was perhaps the greatest limitation of that period. You know, Nam June Paik was always situated at the apex of these kinds of circumstances. As an artist, he inspired people while also getting personally involved in many events and organizations, and he also provided opportunities for many curators, including myself. Of course, he supported many artists as well. That’s why I have always thought of Paik as someone who actually did what the government couldn’t. Without him, establishing the Gwangju Biennale and the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale would have been impossible at that time. Whenever I think about the circumstances back then, I’m reminded that Korea owes a lot to Nam June Paik.

SMB Let’s move on to your tenure as the 4th General Director at SeMA. After you were appointed, there were many changes that you introduced; we might say under your leadership that the Museum earnestly evolved into a “curatorial museum.” The Biennale must have also played a role in terms of your vision for the future direction of the museum, as well as the SeMA-HANA Media Art Award, which was established in 2014. Can you describe the relationship between the Museum and the Biennale, from your perspective?

KIM Prior to joining Seoul Museum of Art, I served as General Director of the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art (2006 – 2010), where I advocated and practiced a “post-museum” management philosophy. Since I was the first General Director of the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, it took an outsized amount of time and research to establish the necessary infrastructure to realize this “post-museum” paradigm. One thing that I was able to do was to lay a foundation by creating the artist residency at Gyeonggi Creation Center. We converted an abandoned school in Seongam-dong, Ansan into a residency and invited artists from both Korea and overseas, in line with the objective of moving forward as a new art museum.

When I later moved to SeMA, its residency program, known as SeMA Nanji Residency, as well as the Biennale were already in place. In other words, I viewed the Biennale and the residency as important driving forces for progressing into the “post-museum,” with the potential to meaningfully change the Museum and unfold a new future direction. I’ve always believed that for an art museum to break from traditional practices and become a viable, renewed institution, such “alternative projects” are absolutely necessary. Before starting this job at the Museum, I had previously gained experience at alternative spaces such as Ssamzie Art Space as well as working on projects such as Gwangju Biennale and the Venice Biennale. Chose to be an independent curator, if you will. That’s why I can say that I acquire my skills on the front lines. I think that having a sort of “independent spirit” served an important role in reforming the Museum and shifting it toward a more enterprising direction.

The first step I took in transforming the SeMA into a “post-museum,” or a 21st century future art museum, was to place the Biennale within the purview of the museum’s direct management. Although it had previously been organized under the auspices of the museum, it was basically compartmentalized into a kind of satellite department that was vaguely management. Although it had previously been organized under the auspices of the museum, it was basically compartmentalized into a kind of satellite department that was vaguely connected to the museum, and there was always a different administrative team for each edition of the Biennale. In short, it wasn’t system in which the Biennale could naturally form a close relationship with the museum, or even receive sufficient support. Therefore, I sought to establish a small, efficient and sustainable organizational structure for the Biennale by bringing it under direct management of the museum by using the model of Gwangju Biennale, which I was very familiar with, as reference. I changed the official name to SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul, and appointed staff to create a general affairs department, which ensured that each artistic director and their respective Biennale team would receive sufficient administrative support. I also included the museum’s curator in the Biennale planning process and encouraged them to stay involved with the Biennale’s tasks, in an effort to properly establish both a system and contents that would be worthy of the designation of an art museum biennial. After this reorganization, Park Chan-Kyong was appointed as artistic director of the 8th edition, and Beck Jee-sook was appointed to lead the 9th edition. I think that these two Biennials, both of which took place during my five-year term as the General Director of the museum, represented an important opportunity for realizing the vision of a post-museum through integrated relationships and partnerships between the museum and the Biennale.

SMB It seems safe to say that the 8th and 9th editions really helped this role and function of the Biennale to blossom by presenting and practicing an alternative to existing art systems or activities. However, while these “alternative” attempts may be understood as novel or innovative statements when viewed today in the context of their successful outcomes, do you think they were considered risky at the time that they took place? I ask this because of the perception that you were moving forward in a direction that others couldn’t yet envision; I assume that you placed your trust and understanding in each artistic director’s decisions because of your previous experience with independent curating at Ssamzie Art Space and the Gwangju Biennale, as you said earlier. Could you elaborate on your perspective regarding the relationship between the General Director of the museum and the artistic director of the Biennale?

KIM The role of the museum’s General Director in that relationship is to support the artistic director in carrying out their responsibilities. During my tenure, I made efforts to provide the necessary support for the artistic directors’ requests, as well as to mediate and resolve issues. I did my best to understand the difficulties of the artistic directors and offer support, as I recalled the 6th Gwangju Biennale Fever Variations in 2006. In addition, I believe that the museum’s curator placed in charge of the Biennale should remain consistent from year to year, so that they could accumulate as much know-how as possible. I think that this would enable different artistic directors for each edition to work productively and in harmonious cooperation with the museum staff, especially the curator, based on the structure and system of the museum in support of the Biennale.

SMB While you were serving your role as General Director of the museum, you also considered Australia’s Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) as a model biennial that was directly managed by an art museum. What characteristics of this triennial were of particular importance to you?

KIM APT is not as well-known as the Venice Biennale or Kassel’s Documenta, but it operates in a unique way; most notably, it focuses on artists in Asia, as well as diasporic Asian artists working in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. This orientation maximally reflects Australia’s regional specificity, leading APT its own distinct identity as an international triennial. It also aligns with the background of protecting and fostering Aboriginal art with regard to Australia’s arts and culture policies. APT is a good model for non-Western biennials because of the balance and harmony that it achieves between high-tech art and Aboriginal art of the Asia-Pacific region. In that sense, it contrasts with several Western-centered Asian biennials such as Korea’s Gwangju Bienale, China’s Shanghai Biennale, Taiwan’s Taipei Biennial, and Japan’s Yokohama Triennale.

The second point to note is that APT is directly managed by Queensland Art Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. In APT’s early stages of development, the director of Queensland Art Gallery was put in charge of the triennial until the project’s structure reached a certain level of stability. Furthermore, the organization employs a professional administrative officer who is tasked with managing the triennial team, has the same degree of authority as a guest curator, and participates in the selection of the triennial’s theme. Eventually, these officers go on to become directors of other institutions and develop into art professionals. To me, these are some of the benefits that are possible when art museums manage biennials directly.

The final important point concerns museum collections. Biennials often invite artists to come and produce temporary works at specific time, yet most of them have no choice but to abandon their works when they leave. However, Queensland Art Gallery didn’t miss the opportunity to collect those works as a type of “presence” collection (improvising in response to on-site situations). As such, Queensland Art Gallery has accumulated a vast collection of works from its previous triennials, either donated by artists or purchased at low prices. In my opinion, the Gwangju Biennale would have been able to build a richer collection and achieve enhanced international status if it were managed directly by, or in solidarity with, the Gwangju Museum of Art. When I was working at SeMA, I undertook efforts and discussions appropriate to the museum’s situation in the hopes of collecting works that were abandoned by artists that participated in the Biennale. However, they didn’t meet my expectations, unfortunately.

SMB The 8th and 9th editions led to more works being registered in the museum’s collection than other editions. And in 2018, Ahn Kearn-Hyung donated his work, which won the SeMA-HANA Media Art Award, to the museum. Also in the museum collection, there is Nam June Paik’s Market (2000), which was commissioned by the 2000’s Organizational Committee and exhibited at the media_city seoul 2000.

KIM In fact, the museum collection is not only valuable from a material standpoint but also as an archive, so the practice of retaining works after the Biennale has a clear objective and documentary function. I hope the museum will keep this in mind in the future.

SMB That is also one of the main points of our current interview as well as the report we are trying to create, with the goal of establishing a basic foundation for professional discussion by paying attention to human resources and their experiences, all of which serve as important resources in the Biennale’s collection, in addition to organizing historical records of the Biennale.

KIM I fully agree, and that’s why I wanted bring my attention to this interview.

SMB Do you think the Biennale should continue, and if so, why?

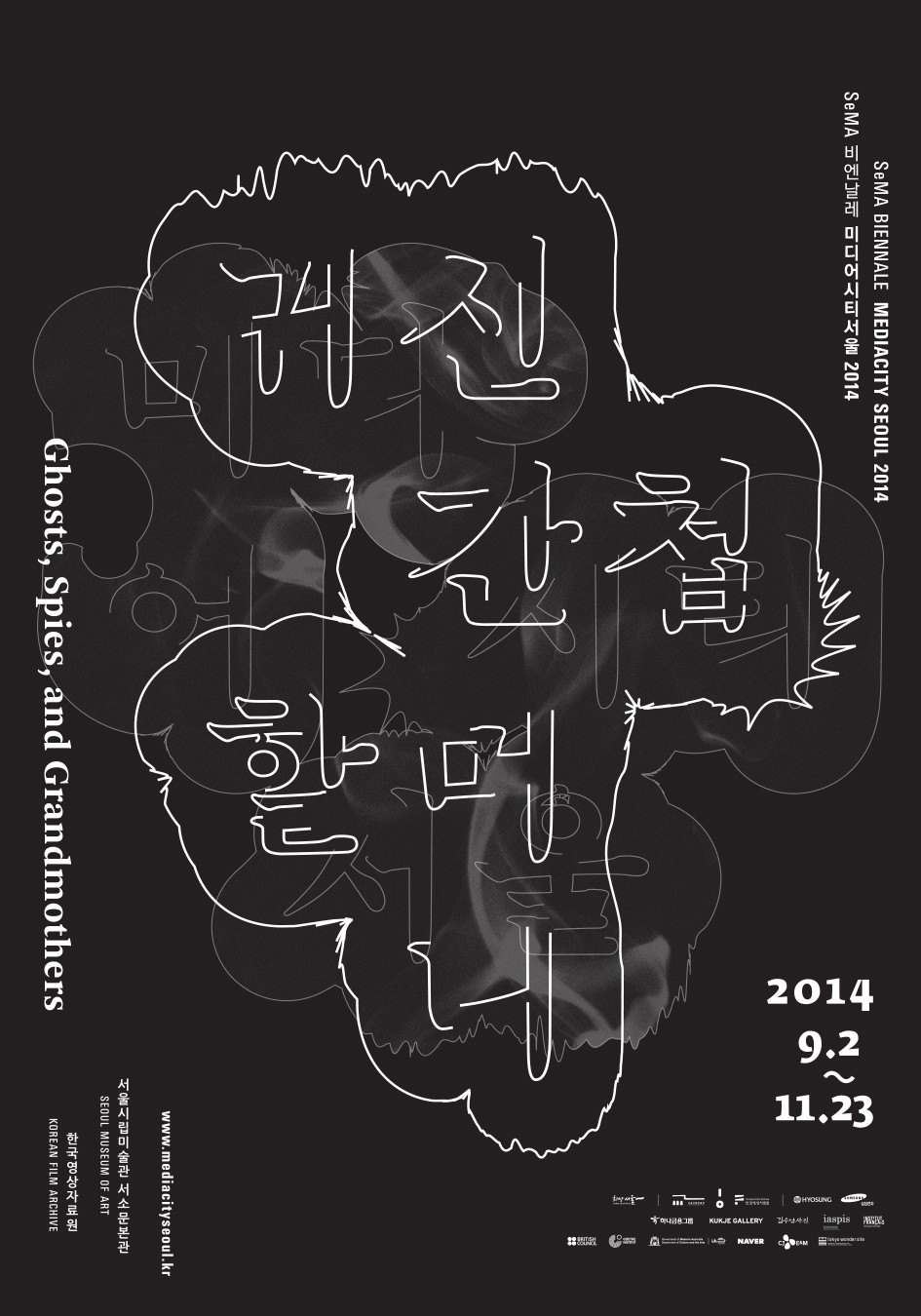

KIM Of course it has to continue. First of all, it’s important to talk about the alternative imagenaries of the Biennale and its role as the driving force to lead change. In the ecosystem of the art world, the significance of the Biennale becomes a tool for subverting the art world’s stagnant atmosphere or discourse. While there are some people who endorse a negative view toward the Biennale as a food chain of famous international curators, it is nonetheless a platform for attempting temporary works, projects, and minority aesthetics that would not otherwise be accommodated by the museum. SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2014 Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers paid attention to “Asianness” and symbolized marginalized people by metaphorizing and personifying Asia while delivering a subversive and future-oriented message that foreshowed new waves or prospects. That theme really resonated with me. It revealed the oppressive elements in our lives and effectively imprinted the theme of Asia onto broader public discourse. The opening ceremony included an actual gut (shaman ritual) related to the Biennale’s theme at the museum, which elicited participation of the audience. This had a strong impression on me because I believe that another essence of the “post-museum” is its state of being public, or in other words, lowering the threshold of the museum and visualizing an unseen audience. On the other hand, SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016 NERIRI KIRURU HARARA was meaningful in its engagement with sharp, relevant topics such as minorities, the disabled, social education, and environmental issues. Essentially, one Biennale focused on the public awareness of Asianness, while the other proposed the aesthetic topic of the “other,” both of which fulfilled the alternative function of the Biennale. I’d like to offer positive evaluations of these two editions based on their achievements, not simply because they took place during my tenure at the SeMA.

Second, the Biennale can become a tool for the geographic and cultural expansion of Korean wave, which has taken hold among young generations throughout East Asia. I believe that we can unlock the potential of “K-art” through the Biennale. The Korean wave already appeals to new generations of East Asians seeking new cultural identities and embodying the cultural hybridization represented by Korean wave, or contemporary Asianness that subtly combines Korean and Western characteristics. Therefore, an East Asian biennial like Seoul Mediacity Biennale can operate as a functional locus for the Korean art wave.

Third, considering the urgent need for individuals such as curators, critics, and coordinators to support the work of artists, the Biennale can also serve as a personnel platform. Korean art can only grow internationally if competent organizers can be found who can interact with important international figures in order to hold a successful biennial. Great artists cannot showcase their abilities on the international stage alone unless they are introduced by or collaborated with someone else.

Finally, the main reason why I believe that the Biennale must continue is the project’s historicity. From the very first edition held at the start of the new millennium, it was always a city-specific event that considered the close linkages between the history and structure of Seoul, and it has made great contributions toward establishing Seoul as an international city. Considering its ability to change the cityscape and enhance citizens’ imagination in conjunction with arts and culture, based on science and technology as well as development of media, the Biennale should be seen as an essential cultural partner for the city of Seoul.

SMB COVID-19 has changed how we experience arts and culture, not to mention many other aspects of our daily lives. With this in mind, what are your thoughts about how the Biennale ought to operate in the future?

KIM The Biennale should not pander to traditions or conventions but sincerely pursue its function as art and as an alternative organization that awakens and stimulates people by engaging with new topics. It must also take responsibility for transforming the ecosystem of art within a continuum that fulfills and emphasizes such duties. As I think about the future, it will be important to develop a language of art associated with the post COVID-19 era. Aside from technical information and knowledge of Blockchains, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, robots, and big data, what is most necessary is a “non-face-to-face marketing” in the context of comfort, healing, moral value, and publicness. But most of all, we must continue to question the essence of art as something distinct from industry, technology, and science.

Through art we can enrich people’s lives and anticipate a future of shared love for humanity, and this is why I believe arts and culture will never disappear from the human world.

Interview Date: February 8, 2022