Media Art

This interview is a conversation with artist Yangachi about media art and the Biennale. It is a re-edited version of the interview from the Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996-2022 Report, published in 2022, with the addition of relevant images from 2024.

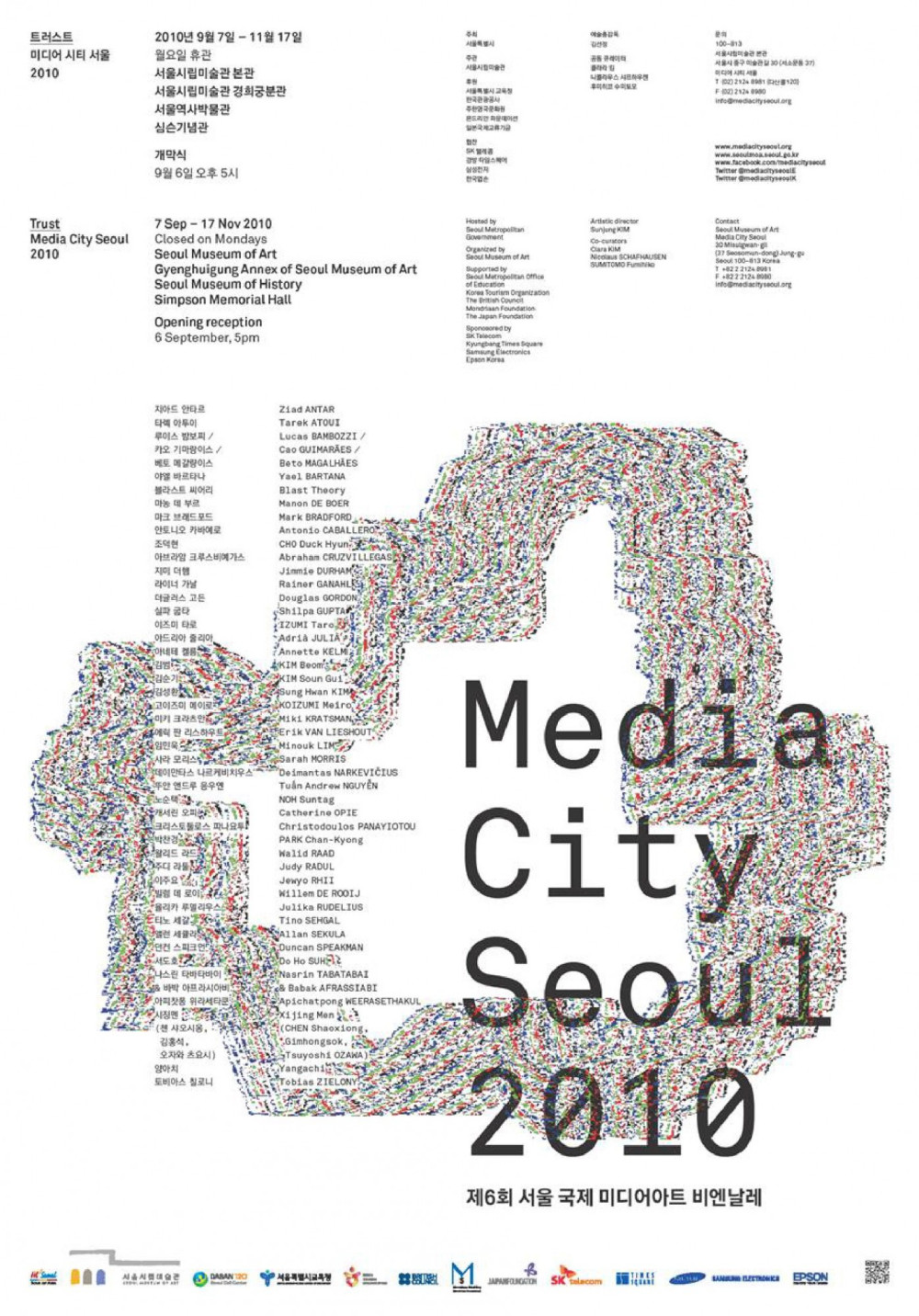

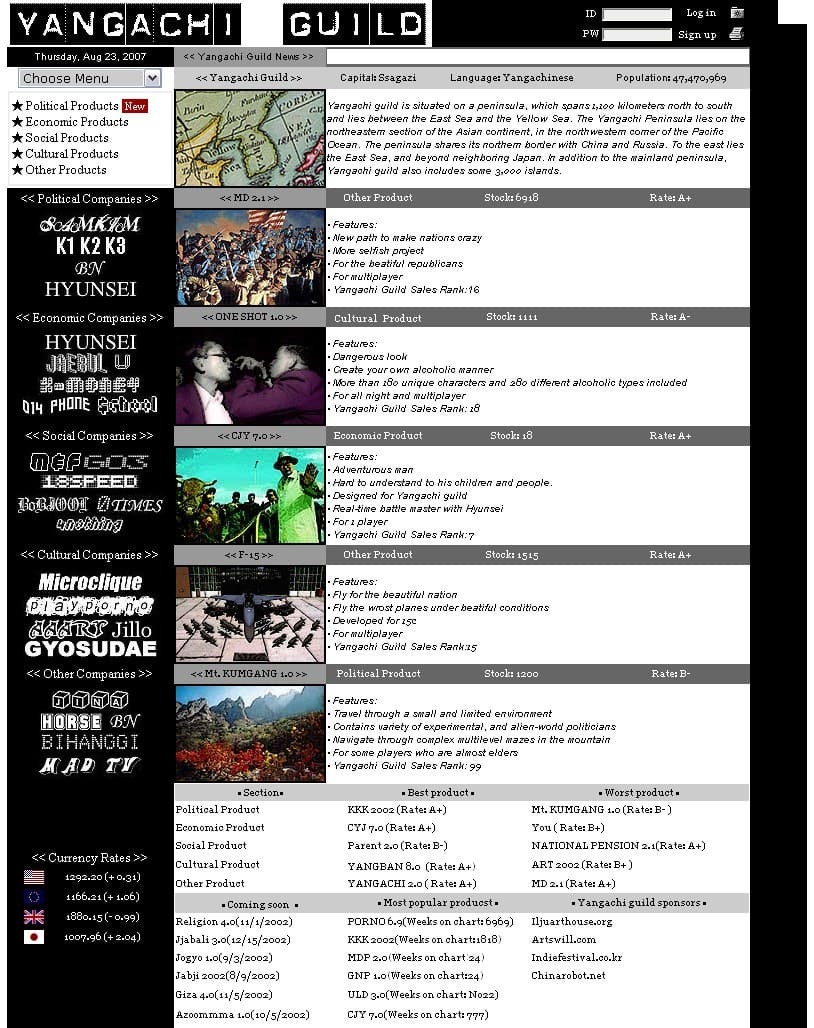

Yangachi was a participating artist in Media City Seoul 2010 Trust and the 10th Seoul Mediacity Biennale Eu Zên (2018). Since the early 2000s, he has explored the social, cultural and political influence of new media in his web-based practice. His notable works include Yangachi Guild (2002), which compares the contemporary Korean landscape to online shopping; Middle Corea: Yangachi Episode I, II, III (2008-2009), which contends with the influence of storytelling in the media; and Bright Dove Hyunsook, Gyeongseong (2010), which depicts modern people in the city’s surveillance camera network. He won the 11th Hermès Foundation Art Award in 2010 and his works have been acquired by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul Museum of Art, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, and Amorepacific Museum of Art.

Research Title Media Art

Category Interview

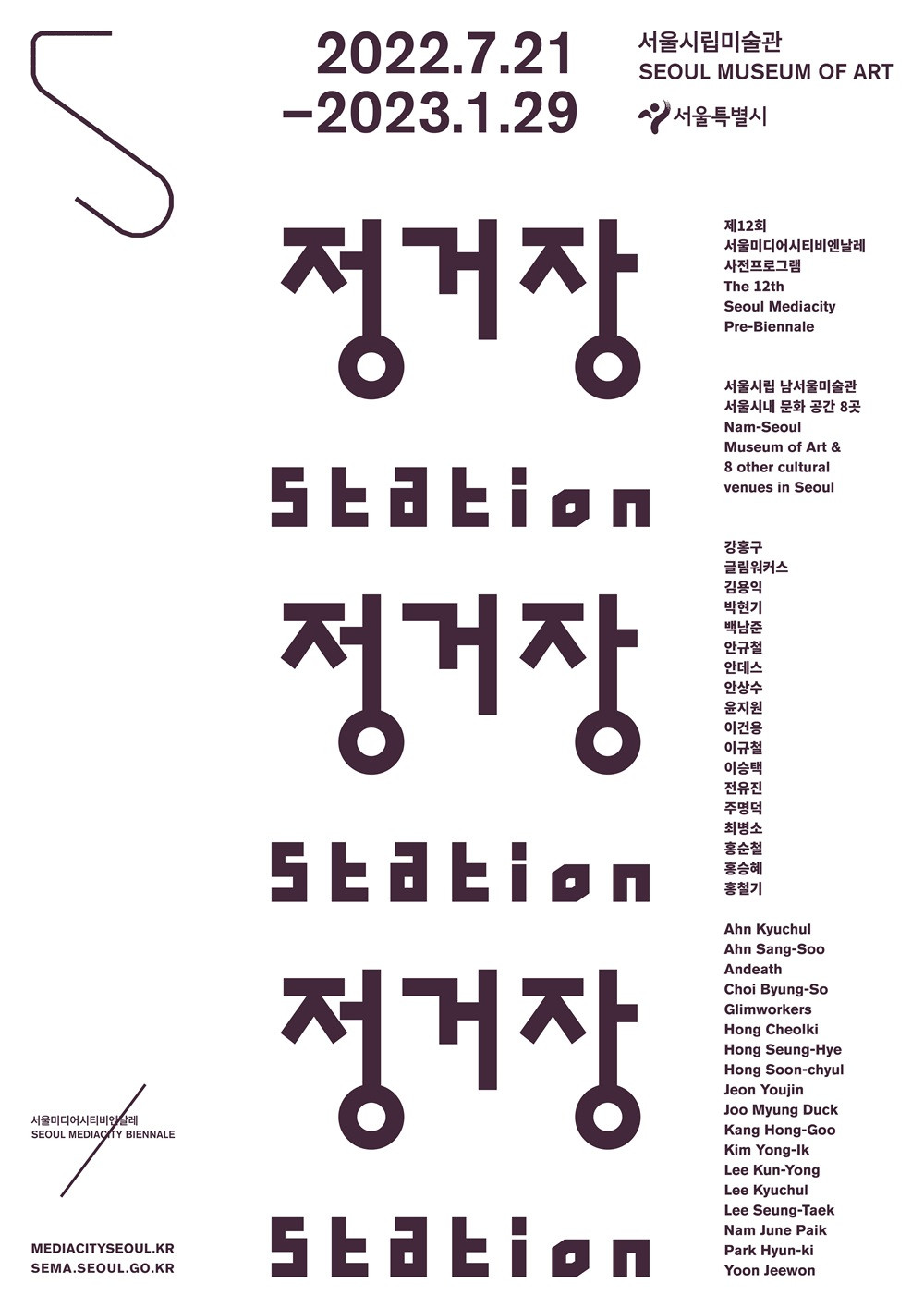

Edition The 12th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Participants Yangachi, Seoul Mediacity Biennale Office

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

SMB Your art career began in the early 2000s when you earned the distinction as a “web artist” and presented a solo exhibition, Yangachi Guild at Iljoo Art House in 2002. Can you describe the types of artistic attempts that characterized that exhibition?

YANGACHI (YANG) I think we need to clarify some terminology first. My work is generally termed as “web art” in Korea, but as you know, originally it was considered “net art” or “net.art.” I think Koreans started calling it “web art” out of convenience. Before I started working in Seoul, I lived in Boston for a while. Since there are so many universities, the internet was naturally the driving force behind many new activities in Boston in the 1990s. During that time, I took open classes at several universities and got to know some professors and students who, in retrospect, included some great corporate executives as well as prominent scholars and activists. But there were also many young people who were actively taking part in activities on the Internet. Thinking back to my encounters around the Boston’s Charles River, like Seoul’s Han River, and what was happening on the Internet back then although I can’t name them, I recall that there were some very impressive online initiatives. In particular, there seemed to be a sense of organizing something new on the Internet, but without the familiar social conditions of people meeting and parting.

In 1996, I launched an online community called China Robot, which I operated until the IMF crisis, when I returned to Korea. After that, I moved around the country to meet and interview people because I wanted to introduce Korean artists to the outside world (through the Internet). It was a time when alternative spaces were starting to emerge in Seoul and art students at Hongik University were flocking to the web and writing papers, creating frameworks and phenomena of activities that were distinct from the existing aesthetics. As a result, I naturally met people who were interested in such areas, including Yun Cheagab and Kim Jang Un, who were very enthusiastic about internet culture. These are some of the things I remember about my interests and experiences before beginning to make “net art” in 2000s.

SMB Whom did you meet in the interviews?

YANG It’s difficult to remember individual interviews because they happened so long ago. YouTube wasn’t around at that time, but we still used the term “underground” back then, right? Nowadays, YouTube has absorbed the entire “underground scene,” but Korea definitely had such an underground culture, and that’s where I met and recorded the stories of various people including tattooists, social activists, and feminists.

SMB So your interests leaned toward the creative base of the “underground culture” rather than being media-oriented, and you were subsequently introduced as a “net artists” in the art scene?

YANG As soon as I came to Korea, I became attached to media environment here and I felt that there was room for developing my practice here. At that time, the word “media” wasn’t commonplace in the art world, let alone the web, there was only “video art,” which is different. Today, media is understood more multidimensionally, but it was very difficult to explain the idea of media back then. So I thought that I would perhaps do media work, but maybe not art. Somehow I came into contact with Jinbo Network http://www.jinbo.net around the same time, which resonated with my particular focus at the time. Are you familiar with the bulletin board culture known as Bulletin Board System (BBS)? Jinbo Network was responsible for creating and processing the open-source concept of BBS. Creating websites used to be very expensive, ranging from five million KRW to tens of billions of KRW. Jinbo Network was preparing to set up its administrator mode with open-source software, which was a technology that I wanted to translate into art. Also around that time, the immigrant network websites was being created.

So that’s basically how I understood internet network culture back then. There was also the labor network, whose videos recorded encounters of labor movements and media, then immediately transferred them overseas. So a group similar to a “performance crew” from the old days became a type of video crew by recording and distributing the daily events of the labor movement. Back then, the internet was considered an elite-centered culture in Korea, and when I saw these things actually happening in Jinbo Network or the labor network, I thought that they represented the essence of art and culture. Long after these things unfolded, the term “web art” became popular, although art has since erased such contexts.

SMB In that case, the language or understanding that was actually shared through art must have been different.

YANG That’s still true. This interview also began with the term “web artist.” I was surprised when the field became known as “web art” without any discussions or controversies. In the 2000s, I decided to pursue art as a profession and applied to Iljoo Art House. The programs they were offering centered on the concept of public media at the time, and this orientation really coincided with my work – for instance, I believed that media was public by nature. The organizers of Iljoo Art House’s programs aimed to expand the concept of media beyond the so-called category of “video art” and I think they were looking for artists like me. As for myself, I also needed people who viewed art from that perspective.

The web project Yangachi Guild, which thematized data, was created amid these circumstances. Data was obviously the most important subject for me, but Korea’s art scene paid more attention to Flash. I don’t know if you remember, but animation-focused contents such as Zolaman were such a hit that they almost became a cultural phenomenon, and Flash was the tool that most people used to create animations. I think the art world paid attention to the projects created with these tools because they were visualized rapidly. Unintentionally, I became the only person who spoke out about data. When everyone was doing Flash, the term “web art” began to surface as a way of characterizing the new phenomenon. That’s how the timing worked out.

SMB Recently I’ve got to know that Iljoo Art House organized a new artist support program that foregrounded the “publicness of media” as its core philosophy at the time. The program was a hybrid between a media art lab and an incubating program, which supported artists researching and experimenting with the publicness of art by using media as their medium. Do you remember anything more about the program?

YANG There were so many. First of all, the program’s organizers were Park Samcheol and Lee Sop, who were such important people. Then there were people like Lee Chae-young, who is now working at the Nam June Paik Art Center, and Kim Yeon Joo, who operates Culture Space Yang in Jeju-do Island. I think people like these really made tremendous efforts and contributions, and they must be remembered by the art world. There were many artists that followed, I recall that Bae Young-whan and IM Heung-soon were there as well … so many artists. People usually associate artist residencies with spatial support, but what actually took place there was media education. They offered equipment training, which is the most valuable thing in media work. I think they saw clearly that there are many issues that cannot be solved simply by providing space for artists.

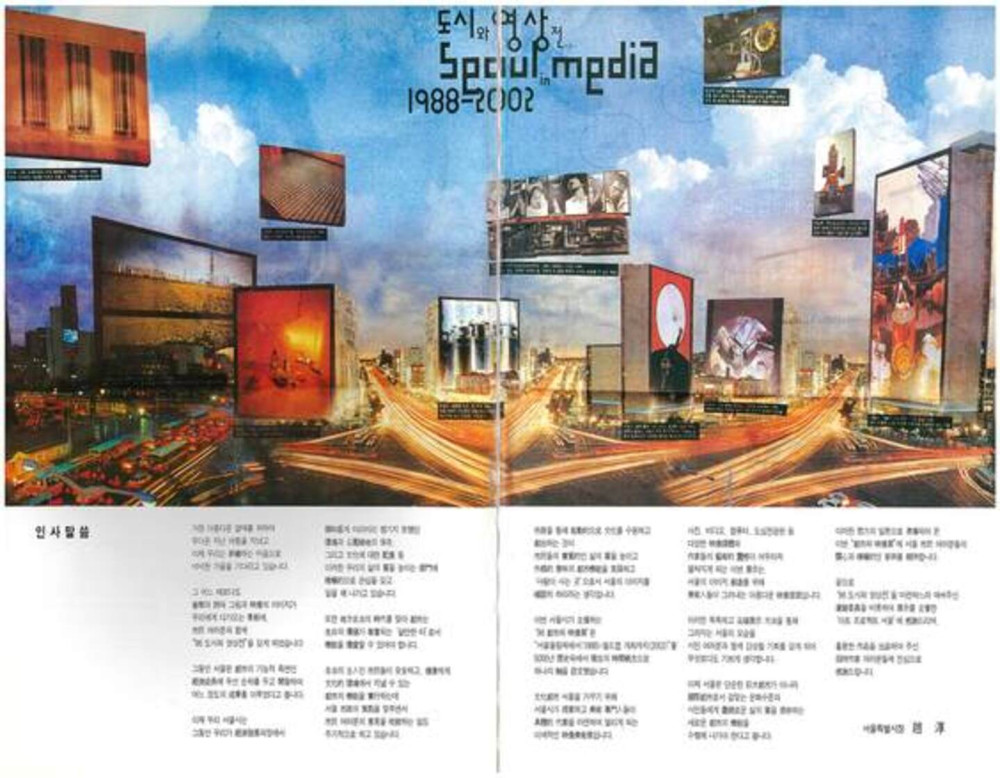

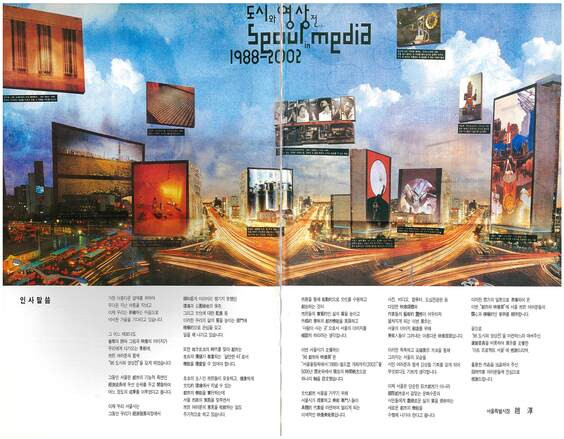

SMB In 2000, the city of Seoul organized media_city seoul as a large-scale biennial exhibition encompassing art, technology and industry. The project was transferred to SeMA in 2002 and has operated in its current structure since then. While the project’s early editions focused on works that presented active combinations and convergences of art and technology, it seems that attempts were gradually made to change its direction toward adopting the model of a so-called “art biennale” in 2010, which was the year that you participated. What do you remember about the changes and evolution in the Biennale since you began your career?

YANG There were a lot of interesting things. At that time, the budget was huge, but there were also tremendous efforts to connect media and the city, which was seem as a natural correlation. However, it ceased to be natural after the project began to embrace art discourses. The power of art essentially lies in interpretation and translation, but when these imperatives only occur within the walls of the art museum, no connections can be made with the city. I think that the aesthetic attitude and actions at the time, of trying to combine the importance of interpretation and translation with the city’s dynamic, were truly amazing.

SMB So you sensed a gap between the works presented in the Biennale and the media phenomenon throughout the city? Can you explain this gap, according to how you perceived it?

YANG I remember the interesting predicament of introducing media to Minjung artists (LAUGHS) It’s unthinkable now, but senior artists used to come to me and ask me to teach them how to do web art. Aesthetically, I think it’s natural for “web” and “Minjung (the people)” to come together, but because of the generational gap, the senior artists had trouble understanding the concept of the web or new media. Anyway, I thought it was remarkable how much they wanted to learn about it.

Furthermore I think that in art world back then, “web art” tended to prefer Flash rather than data (as a methodology of display), which prevented it from delivering a practical (digital) mode of operation.

SMB Bright Dove Hyunsook, Gyeongseong (2010), the work that you exhibited at the 6th edition of the Biennale in 2010, is now in the collection of SeMA. You used the museum’s rooftop overlooking Deoksugung Palace as a performance set - filming location, allowing the surrounding environment and the narrative of Seoul to be visually integrated into the work. Can you tell us how this work came into existence?

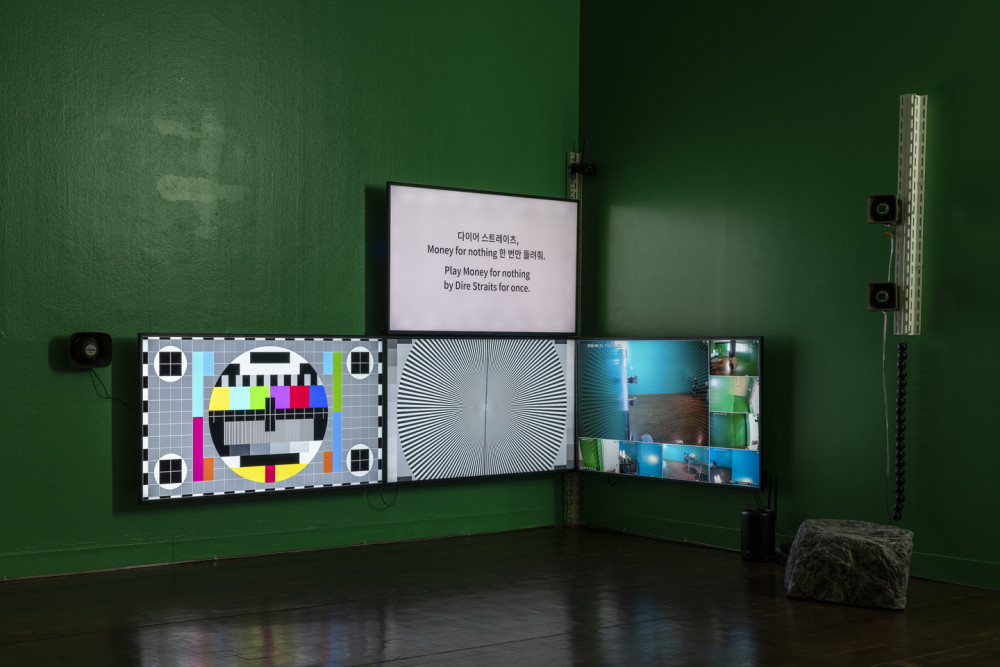

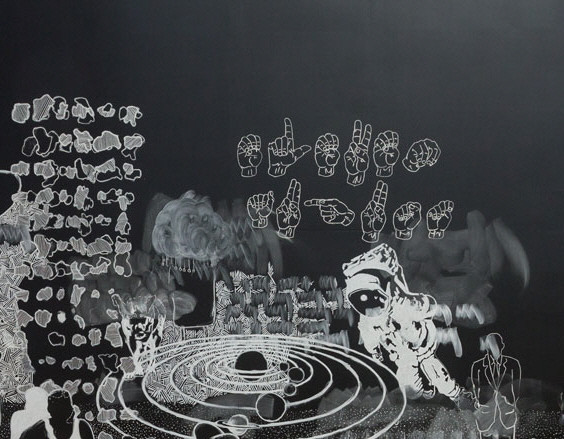

YANG As you know, “surveillance” is a keyword in my work and Bright Dove Hyunsook, Gyeongseong attempted to look at society through surveillance cameras that populate our environment. The work used an array of channels, ranging from six to thirteen, and illustrates both conventional survillance and reverse surveillance – through the two eyes that we all possess as well as the eyes that are connected to the city. At that time, media art was understood as something very cold and dry that was characterized by linear formation, but I didn’t agree with that. I wanted it to blend in the environment completely and appear like an object that was simply sitting there, so I presented it such a way.

As for the performance you mentioned, that was during a labor movement protest at Seoul City Hall, which caused so much noise that it disturbed the exhibition viewing inside of the museum. And the clock at the Anglican church nearby always rang at six o’clock, when we filmed the performance. But I noticed that everything I could see and hear from the rooftop of the museum was so beautiful, from the amplified shouts of the protest on one side, to the preaching of the gospel on another, to the order and disorder created by people pouring out of the surrounding office buildings at six o’clock. I planned the work accordingly, hoping to show all of this scenery.

SMB Revealing the city’s surveillance network and the operational capacity of media, as manifested in the work’s context of web algorithm, initiated an interesting trajectory in your practice that led to the issues on contemporary collectives. It seems as if the changes in your oeuvre can be interpreted with respect to the Biennale’s own changes throughout the years, as well as with regard to the perspective of media art. How would you explain the changes in your work or the inspirations that inform your practice?

YANG Well, people who see my works often say, “There are too many changes.” However, despite any format changes, the conceptual aspects or subject matter of my works have remained quite consistent‐surveillance and reverse surveillance. There is the screen issue, as well as the positions that move within the network, which we often say are objects, especially these days. I presented Yangachi Guild at my first solo exhibition and what I suggested at the time was “emailing objects.” In other words, sending data. Of course, there was no such concept back then, but now the concept of objects has expanded to include “objects” and “things.” At that time, the term “object” wasn’t used when talking about data, although a few people involved with networks did use the term “post object.”

We currently make different formal decisions, but “virtuality” still lies at their core. Everything may look different from the outside, but the virtuality possessed by the web/net continues in the exhibition space, and so I keep putting things out there. Originally, we didn’t consider the web as a virtual space. We used phrases like augmented reality, whereas a virtual space has no physical force – the gravitational forces operating in real space are simply converted into X, Y, and Z coordinates so that they can operate in the virtual space. We talk about bodies a lot nowdays, but the discussions taking place back then about the kinds of spaces that preclude bodies form intervening were always interesting. In any case, that sort of attachment to virtuality continues today and the formative choice of perspective within the virtuality of a real space is still interesting.

In Bright Dove Hyunsook Gyeongseong, surveillance cameras take the perspective of the city we know. While I was preparing for my solo exhibition Galaxy Express (Barakat Contemporary, Seoul, 2020), I learned about a media technology called LiDAR, which allows you scan the city. The scans produced using LiDAR generates very accurate data on a subject by locating more than 100 million points per second. A point here is a data value, which can become a point of view or a subject with this technology. I was really pleased to encounter a completely open type of perspective with LiDAR and I wanted to utilize this in my work in ways that support the language of art, so I realized new works in sculptural format, which is medium that everyone can understand. Regardless of that, my works don’t really deviate from the themes that I’ve always been interested in. However, I understand why some viewers cliam that the outputs look vastly different.

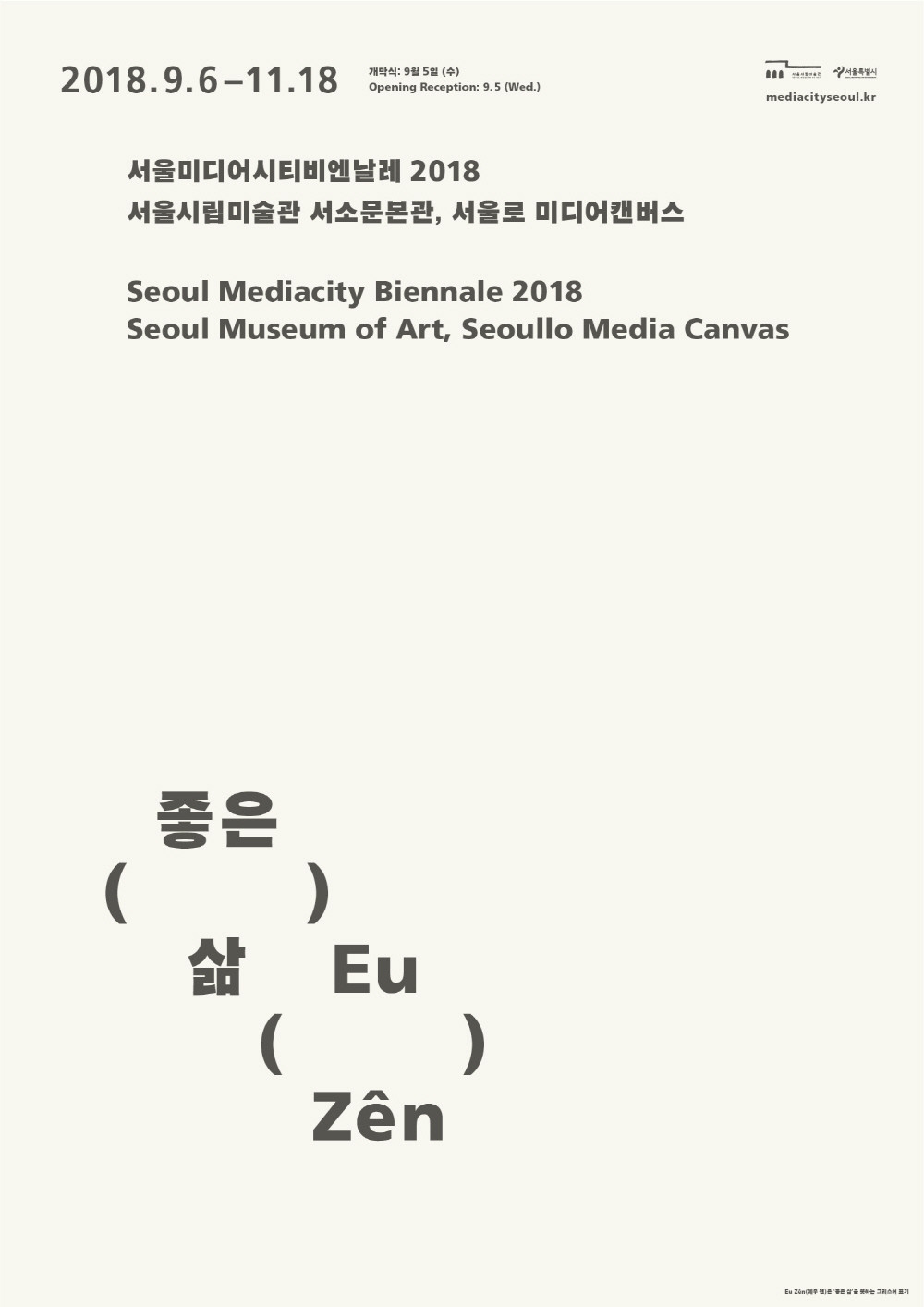

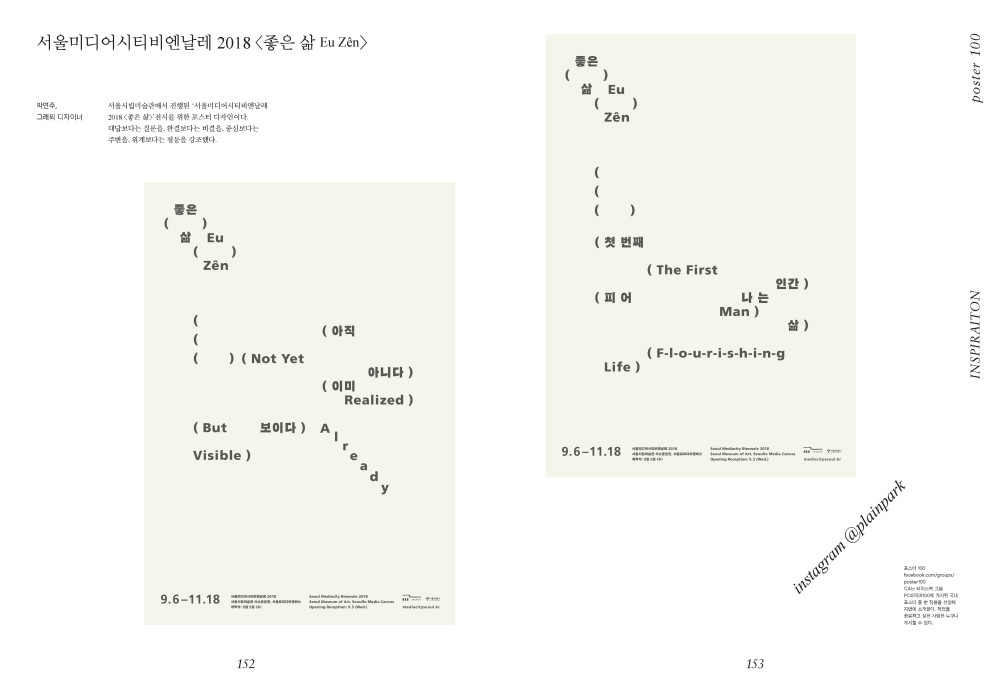

SMB What was the background for developing Credit (2018) and in what ways did you utilize new or different technology?

YANG The theme of the 10th Biennale was “good life.” I even wondered to myself, “Is this a satire?” (LAUGHS) The “new normal” that I was familiar with was different from the vision of the Biennale, but I was still curious about how various coordinates of food, clothing and housing could be interwined through art, and I was taken aback by working directly with such a big idea. At the time, I was actively studying financial and capital issues. Of course, concepts like Bitcoin or blockchain have become part of our daily lives today, but such things were relatively stalled when I was developing that work. The essence of blockchain technology is credit; if existing currency gives a central bank the right to establish credit, virtual currency grants us that credit. I thought this was an especially important point. While working on Credit, I felt that such discussions were necessary, even though we weren’t completely ready. The work doesn’t directly depict virtual currency, but rather portrays the media environment and landscape surrounding virtual currency.

SMB You said earlier that your works using LiDAR was created to “support the language of art.” Can we say that this idea is related to striking a balance between technology and art? After all, art can be voiced through technology, in a virtual sense. With this in mind, how do you define media art?

YANG I think there are many important points related to that question. First of all, technology is really important for our society, not just for art. If you ask people whether art or technology is more important, I’m certain that most people will choose technology.

Contemporary art is a kind of force that is structured by interpretation and translation. Of course, it can’t always be put so simply, but I think that we need to pay attention to Lee Sedol’s retirement. Here is a human being who was the best at interpreting and translating the game of Baduk (Go), until coming up against big data which is the technology of interpretation and translation, and subsequently leaving the world of competitive Baduk (regardless of winning or losing). Contemporary art, however, continues interpreting and translating. If we seriously consider the technological aspect, I think that the Biennale should attempt to develop a new approach toward traditional interpretation and translation. The current method of operation continues with a repeated approach on the interpretation of technology and art, while only the people changes. So we are left with no choice but to ask what recourse do we have, aside from interpretation and translation? I am also looking for an answer.

Perhaps the concept of “verbs” hold the answer. I think that we have become unable to use “nouns” because our “verbs” are out of data. As such, curation should be centered around “verbs” and not “nouns.” By undertaking new research, we should locate the concepts and formative methods for creating viable networks that can encompass existing things. That’s why I want to tackle the issue of “verbs.”

SMB By “verbs” do you mean actions that actually operate concepts, or rather ideas themselves?

YANG I don’t say this because I think it’s the answer, but as a society we tend to differentiate ‘objects’ and ‘things.’ As you know, ‘things’ are related to the “Internet of Things” (IoT) and refer to networks that regulate the transmission of information. In that context, art cannot be a ‘thing,’ according to the prevailing perspective. Instead, art is seen as nothing more than a bunch of machines and electronic network connections. This is the crisis that is currently facing the art. It isn’t simply an issue of electronics both art and technology are nouns in the context of new connections and becomes highly limited ‘objects’ like those you can see on the desk in front of you. But ‘things’ have the potential to transform themselves.

Over time, people have made various efforts in this regard, such as attempting to deconstruct a desk (art) through interpretation and translation. However, after realizing that such objects only exist in the context of interpretation/translation/market, the whole situation has turned into a game that’s no longer interesting. This is why I feel that we need a verb-based approach. At a forum I attended yesterday, an older artist was criticizing young artists based on the reasoning that young artists were creating works as activities without bodies. It made me disappointed to think that nowadays you can have a hundred bodies coexisting in numerous media environments through multiple IDs, with each body issued by a different physical sense. That’s why I think the perspective for distinguishing between ‘objects’ and ‘things’ is very important. I believed that the framework of verbs can remove these accumulated limitations and effectively update art as a completely different form.

SMB Many people say that repeating the Biennale in the same way that it has been organized for the past 11 editions is unfeasible. This interview may be part of the attempt at finding something new. We need to analyze the project’s future prospects, yet doing so has been complicated by many things; the change in the environment caused by COVID-19, the change in the Biennale’s paradigm, and the specificity indicated by the Biennale’s name that has constantly changed since the project’s inception. What do you think the Biennale should be like in the future? Do you believe that the Biennale ought to continue?

YANG Obviously, I have an affection for the Biennale. I was so glad that they created such a project in the beginning because I could see all human imaginaries were actualized back then in Seoul that would have been impossible in the USA. Apart from my preferences in terms of work, the spaces that I study become scattered all around the city. The city and media complement each other so well, as if it is a natural correlation. But when this relationship is brought into the museum, it becomes a little insignificant. Since the museum is a space devoted to interpretation and translation, this results in the perception of building a career based on mutual interdependence. Meanwhile, I do perceive a kind of signal.

There are so many big issues that surround us today. For example, AI has recently become a popular topic, but in art we only think of it in the context of “AI art.” As for mobility, it’s “mobility art”; for robotics, “robot art.” Everything is just simply titled as if it’s a genre in art… (LAUGHS) If we consider the AI chatbot Lee Luda, which was quite controversial last year, we can detect a strange algorithm that uses technology and data calculation. But in art, this technology was treated as an instance of sexual harassment from a strictly ethical perspective, which prevented it from being used prudently. Of course, ethical criticism is necessary, but it must be accompanied by aesthetic criticism. Another example was the time that a fire broke out at the Ahyeon-dong branch of KT Corporation, causing most people in Seoul to be unable to access data telecommunications for a while. It is possible to think about the “new normal” that has emerged from incidents like these. Likewise, we can find art from our everyday lives. It’s been said that AI developers can create cubism or expressionism, as long as the algorithms are fed the relevant keywords and images. And yet, I think that artists shouldn’t just nod at such things because the true power of art is in its capacity or willingness for liberation.

Interview Date: March 3, 2022