Museum and Comic World

In this research, Yeonsook Lee (Rita) revisits the history of the Seoul Mediacity Biennale to reveal moments of contradiction, division and the complex relations between art institutions and subcultural/subaltern subjects in Korea.

Yeonsook Lee (pen name Rita). They write about popular culture and visual arts, with a particular interest in modes of existence of minority subjects. As a member of the editorial and curatorial collective “Agrafa Society,” they published the web journal Seminar and co-organized feminist lectures and criticism under the project name “OFF.” They maintain a blog at http://blog.naver.com/hotleve. Lee received the Excellence Award in Comics Criticism from Critique M in 2015 and the SeMA-Hana Art Criticism Award in 2021. They are the author of The Advancing Low (mediabus, 2023), a book examining visual culture and queer negativity.

Research Title Museum and Comic World

Category Essay

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Author Yeonsook Lee (pen name Rita)

http://blog.naver.com/hotleve

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

After confidently accepting the request to write about Seoul Mediacity Biennale (its history) and subculture, I found myself paradoxically unable to write the piece – despite spending months perusing the materials shared by the Biennale preparation team, video archives of past editions of the Biennale, my existing research on 1990s popular culture and various writings on alternative spaces of the 2000s and emerging spaces of the 2010s that seemed relevant to the topic. Truly, I could not write it at all. This wasn’t a typical case of “writer’s block” in which one struggles to articulate existing thoughts. Rather, I couldn’t even fathom what might possibly be said. After considerable self-reflection on this condition, I arrived at a provisional hypothesis:

Perhaps Seoul Mediacity Biennale and subculture … have little meaningful correlation?

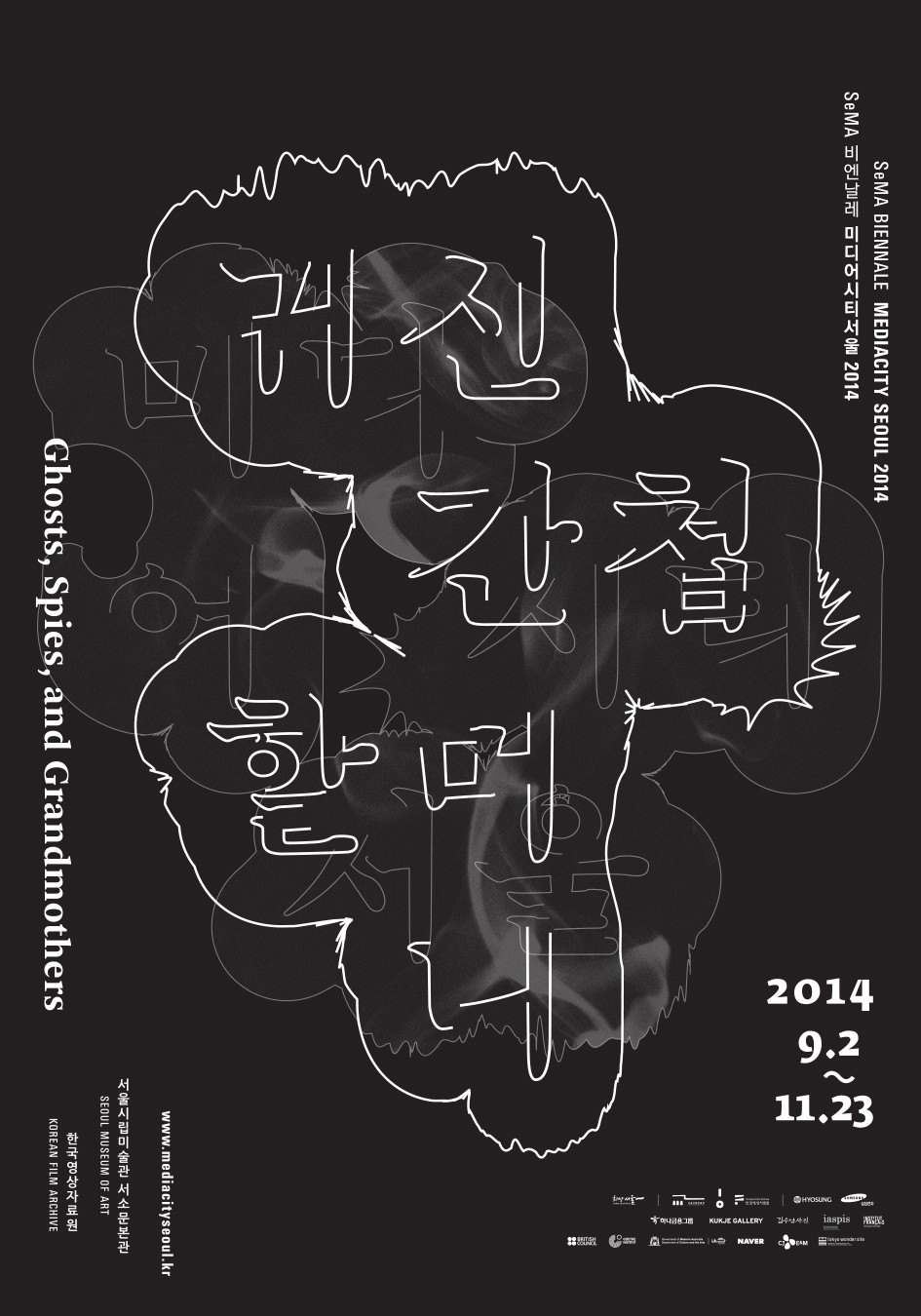

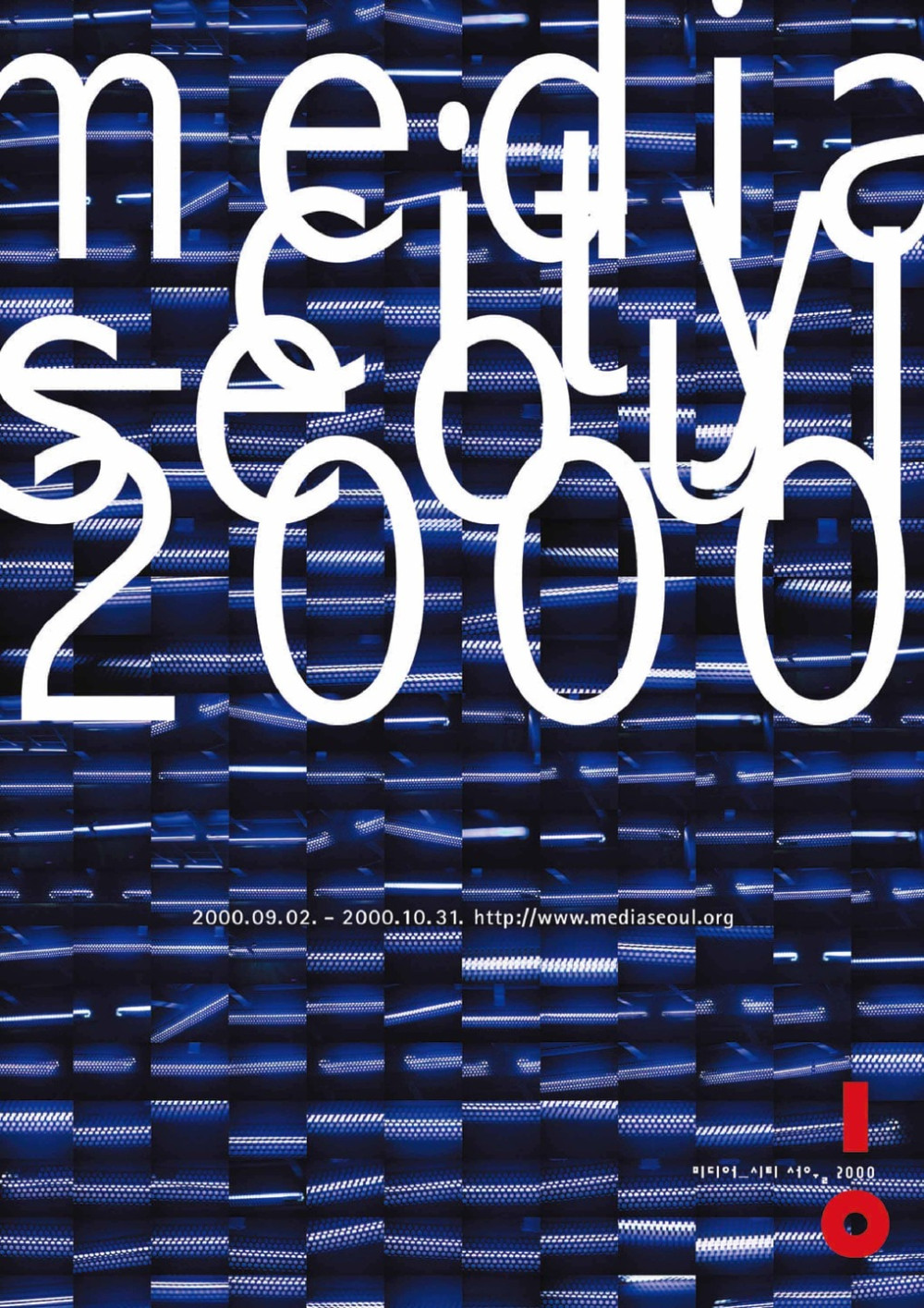

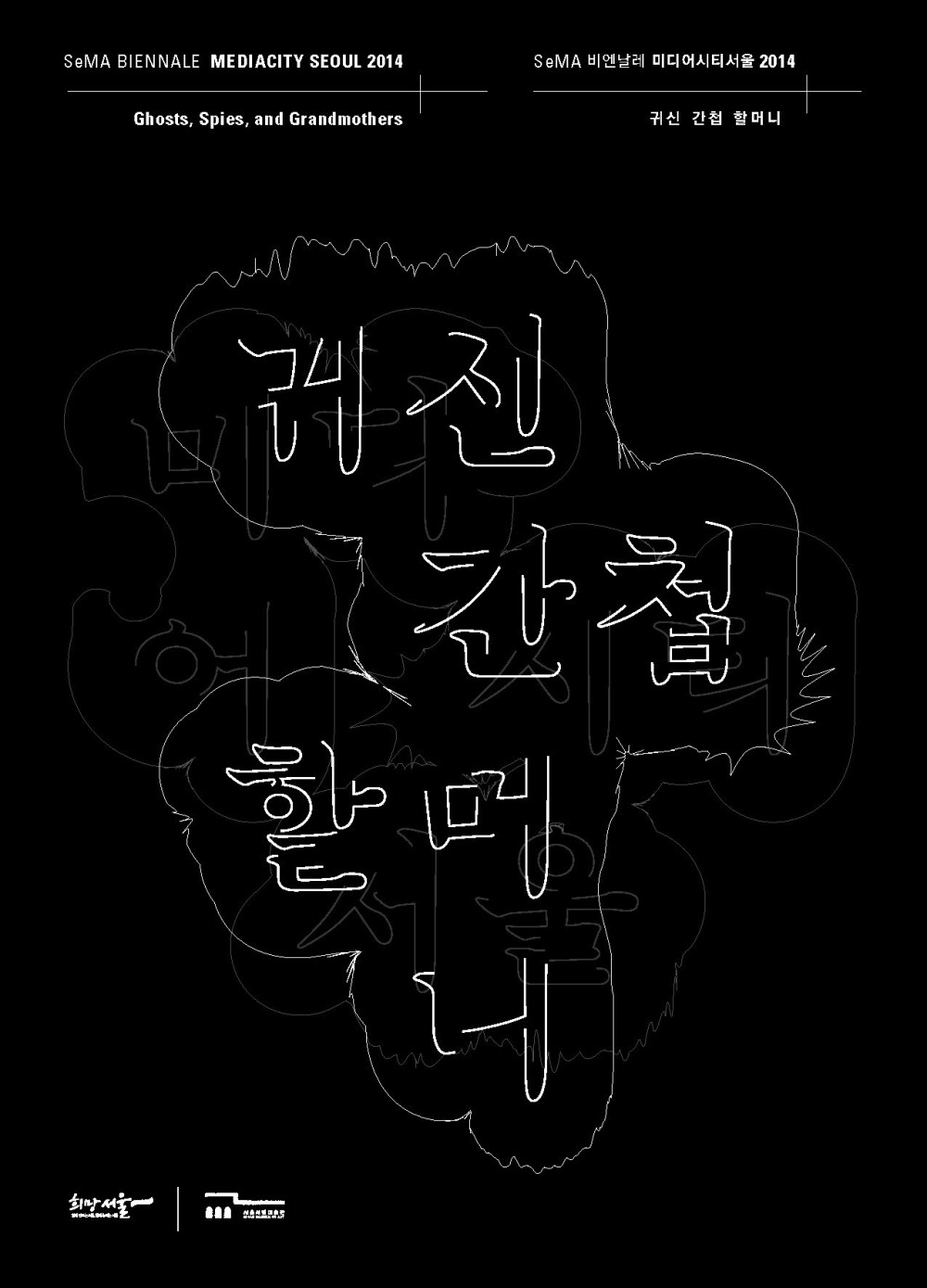

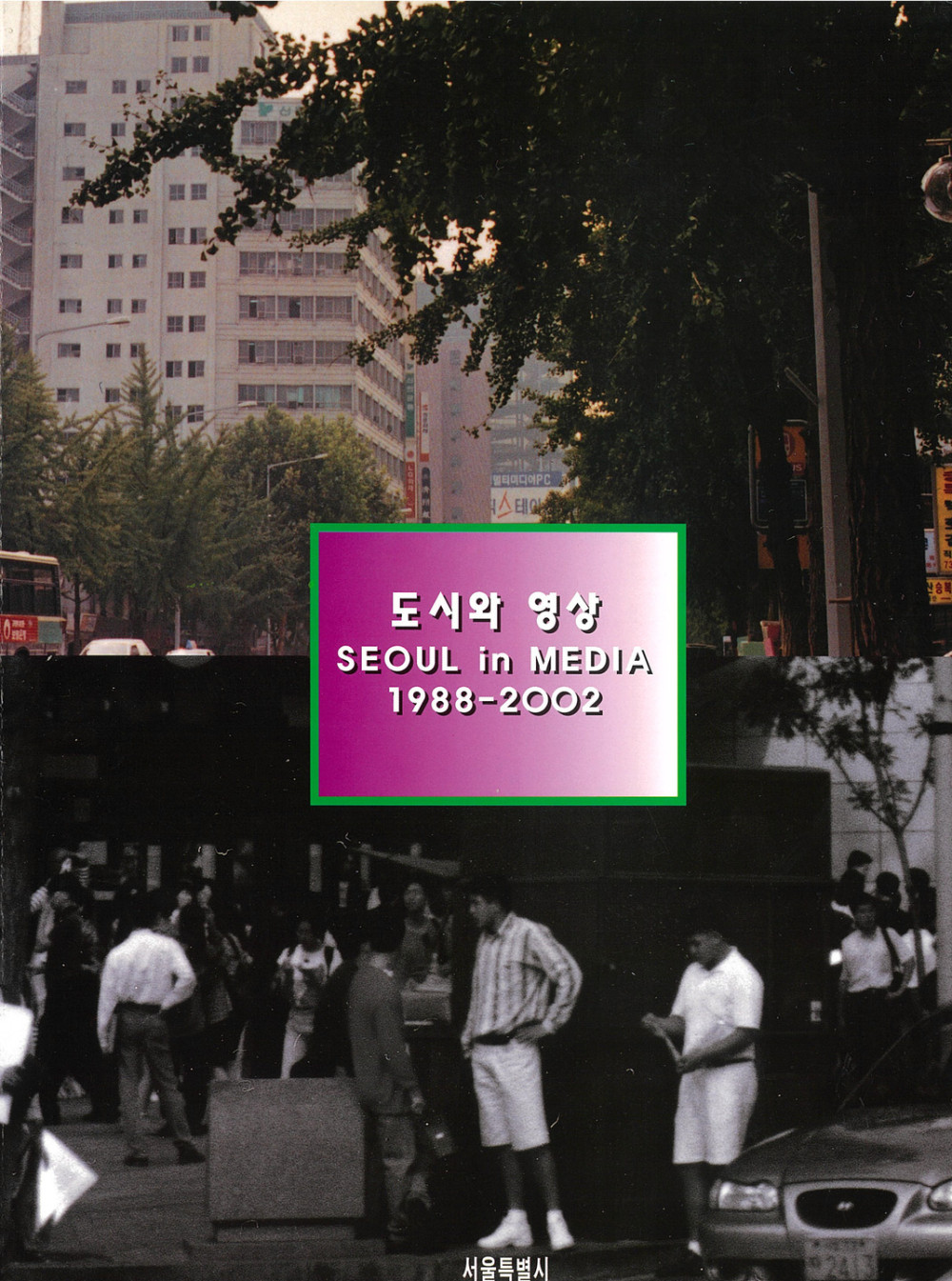

Of course, this essay will ultimately progress toward a different conclusion – that they are, in fact, related. However, I did dwell on my initial theory for quite some time. Readers might find it perplexing that I arrived at such a seemingly superficial assessment, despite having access to all available materials about the Biennale’s 28-year history – from its inception as SEOUL in MEDIA exhibition in 1996, through its evolution into Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul in 2000, subsequent transformation into SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul in 2014, and current incarnation as Seoul Mediacity Biennale in 2019. One might reasonably suggest that even if there is ‘little’ correlation, surely I could explore whatever tenuous connections may actually exist between these entities, given my commissioned task. This is a valid point. Let us begin with some foundational discussions about subculture that most scholars in the field would likely agree with, as a means of explaining (or perhaps justifying) why I chose to adopt this hypothesis as a starting point.

Broadly speaking, the relationship between art and subculture is hierarchical and (parasitically) exploitative. As cultural theorist Dick Hebdige astutely noted early on, even when a subculture emerges as a stylistic movement characterized by its resistance to mainstream norms and values, its visual style makes it easily susceptible to capitalist co-optation and reduction into purchasable commodities. Amid the flourishing consumer capitalism in the 1990s, the counter-cultural and alternative meanings and values capable of being extracted from post-war Western working-class youth subcultures led to an inevitable question: “Does subculture resist?”1 However, this fact itself isn’t the crucial point. Rather, the defining characteristic of subculture – or what philosopher Gilles Deleuze referred to as ‘minor culture’ – lies in its creative mobility to alternate between settlement and deterritorialization. In other words, subculture shouldn’t be understood merely as a community of tastemakers sharing subcultural codes and lifestyles, but rather as a Nietzschean ‘Amor Fati’ – a positive attitude that willingly chooses to wade into the mire, despite acknowledging that its ultimate destiny lies in department stores and art museums. Or perhaps we must view it this way – especially in our current moment where narcissistic exhibitions masquerade as subculture and proliferate on Instagram, all against a background of resurgent cultural tribalism centered on digital spaces.

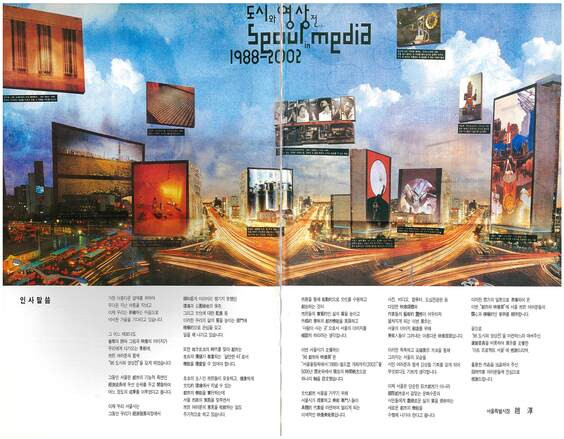

Instagram is hardly unique in this regard. As is well known, ‘high’ culture has long established principles of ‘creative economy’ by renewing its value of ‘novelty’ as a cultural avant-garde through deconstructing, connecting and processing ‘low’ culture – defined as popular culture and subculture – which serves as its raw material. Art theorist Thomas Crow, analyzing twentieth-century art history and its tension with popular culture, has cited various examples to demonstrate the ways in which art and popular culture have continuously transformed and emerged through mutual reference. We need look no further than contemporary artists who appropriate the interfaces and systems of YouTube and K-pop, or the visual signs and ‘aura’ of mass-produced goods and expensive ‘luxury’ items. While far from a novel phenomenon, this should not be criticized but rather understood as providing clues in terms of the intersection of art and artists’ social/political/economic realities, as well as the material foundation this encompasses. Art produced through such a process can, technically speaking, acquire symbolic status as the ultimate ‘non-fungible token’ or ‘international currency’ through its art-historical position. Popular culture has typically depending on this symbolism through simultaneous denial/aspiration, thereby yielding quasi-artistic ‘content’ (although circumstances are somewhat different today). In this context, it is particularly illuminating that in 1996, many pedestrian viewers who happened to see experimental video works broadcast on just fourteen billboards in Seoul during the 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 couldn’t distinguish between the artworks and conventional advertisements.2

Subculture, however – which by nature marks the limits of subaltern subjects’ subjugation and liberation – fails to achieve the somewhat equal and mutually exploitative feedback loop relationship between art and popular culture. While subculture shares affinity with popular culture in its contrast to ‘high’ culture, it remains separate from popular culture precisely because the latter functions as a ‘dominant’ culture. In other words, subculture either aspires to remain ‘outside’ both art and popular culture, or (more accurately) has already been banished to the ‘outside.’ This is perhaps inevitable because subculture emerges from subaltern life, which cannot be reduced to specific codes, styles, rules or symbolic systems. Subculture itself serves as the subaltern subject’s imaginary/real temporary dwelling – simultaneously a refuge where subaltern subjects temporarily escape the oppression of dominant norms and morality, and a laboratory-like space where new modes of existence that were previously invisible in existing society are manufactured through heterogeneous conjunction and convergence of readily available cultural and linguistic resources. Of course, it will ultimately be absorbed into mainstream/dominant/consumer culture; moreover, while subaltern subjects were still optimistically diagnosed as potential resistant subjects until the 1990s, by now they have largely transformed into consumer subjects. Nevertheless, if the term subculture does remain useful, it is only because it provides a limited framework for capturing the terribly tenacious vitality of the lives that inevitably fall through the cracks of ‘normal’ society. This framework is limited due to the fact that style serves a dual function – making life visible while simultaneously rendering it invisible by ‘degrading’ it into something that can be enunciated, interpreted, and represented. This is why style should be viewed not as a direct expression of identity, but as a mediator of representation.

At this point, we can see why the relationship between art and subculture must be fundamentally hierarchical and (parasitically) exploitative (unlike popular culture). When subcultural style enters the white cube space, the life through which such style was cultivated becomes bleached (neutralized). Not just a single life, however – subcultural style is a commons in which all subaltern lives of a specific culture hold equal shares, so that the totality of all their lives is bleached. Just as writer Annie Ernaux described a “traitor to one’s class,” and as philosopher Chantal Jaquet invoked the term “class crosser,” an individual may ‘ascend’ to the white cube, but this does not correspond to a high/dominant culture’s ‘recognition’ of the entire subaltern group. Rather, it is merely a recognition of the individual. This is why artists who successfully ‘import’ subculture into institutional art are exposed to the harshest criticism and condemnation by their own ‘class.’ Moreover, they themselves must inevitably experience division and contradiction in the process of ‘translating’ subcultural style into artistic language, amounting to a wager in which everyone is bound to lose their stake, while capital-A ‘Art’ remains the same. This isn’t to say the entire process is meaningless, but we need to emphasize that the ‘elevation’ of subculture to ‘high’ culture, contrary to common misunderstanding, is something actually demanded by the latter from the former (not vice versa). This is because ‘novelty’ – or more precisely ‘possibility for the future’ – remains an important value in art. Art exploits and extracts the potential of subculture (as much as subaltern subjects), and does so selectively.

… If you sensed that I’m being somewhat cynical, you’re right. You’ve sensed correctly.

Fundamentally, I believe that subculture and art have neither a symbiotic nor an antagonistic relationship. While subculture may be ‘translated’ into artistic form, it is mostly art’s “constitutive outside” – to borrow philosopher Judith Butler’s term – which can never become art in itself. This suggests that art is indebted to subculture as its ‘outside,’ a force that defines art’s boundaries for art to be art . Since hierarchical relationships are anti-relationships rather than non-relationships, I should probably retract my earlier statement that Seoul Mediacity Biennale (which inevitably represents the ‘art institution’) and subculture have “little meaningful correlation.” If we expand the definition of subculture to include culture in general, perhaps Seoul Mediacity Biennale can be said to maintain a similar relationship with the new media culture that emerged after the 2000s. In other words, Seoul Mediacity Biennale functions as an administrative art institution and art reproduction system that examines and selects what can and cannot become art. Today, kinetic art and its relation to craftsmanship and low-tech characteristics was once considered a form of media art that incorporated ‘technology’ into art (even though art was already technology!). By the same token, web art/net art, which in the early 2000s was in its initial experimental responding to the new internet environment, has now become a museological ‘relic’ that evokes nostalgia. In an era where everyone has a smartphone, the term ‘media art’ no longer inspires any wonder, but the question of what sort of immaterial objects and relationships belong to the category of art remains the responsibility of art institutions to interpret and judge.

At this point, I should mention that I didn’t want to spend valuable space airing grievances, primarily because I am culturally indebted to Seoul Mediacity Biennale. As someone born in Busan in 1990 and raised in Gimhae in South Gyeongsang Province, I’ve never felt as if there was nothing to see since my ‘migration’ to Seoul in 2009. This is primarily due to the cultural/institutional/material infrastructure of the Korean art world, which was established by large-scale cultural events organized under the auspices of national cultural support policies and urban tourism industries in the mid-to-late 1990s, which sought to advance ‘globalization’ – most notably the Whitney Biennial Seoul Exhibition (1993), Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (1995-present), Gwangju Biennale (1995-present), Busan International Film Festival (1996-present) and the SEOUL in MEDIA exhibitions (1996-1999) that evolved into today’s Seoul Mediacity Biennale. Today, this infrastructure feels like an integral part of Korea’s art ecosystem. During the same period, we saw the opening of important medium-to-large art museums – Art Sonje Center (1995), Ilmin Museum of Art (1996) and Busan Museum of Art (1998) – as well as the emergence of first-generation alternative spaces centered around Ssamzie Space (1998). While alternative spaces now seem to remain as little more than symbols of the late 1990s and mid-2000s, they continue to influence not only the identity formation of new spaces that emerged in the 2010s but also the perception of the ‘here and now.’ Thus, it is only natural for curator Kim Hong-hee, who served as the director of Seoul Museum of Art from 2012 to 2017, to say that “the 1990s are still alive.”3 Moreover, whether driven by personal desire or public responsibility, various actors inside and outside the art world must have felt compelled to build something from nothing, thereby bearing the burden of being ‘first.’

Earlier, I mentioned being ‘indebted’ to Seoul Mediacity Biennale and for someone like me, the task of reading and digesting its 28-year transformation through archives and records offered the opportunity to settle this ‘debt,’ both as a member of the art world and as a viewer who hasn’t missed a single iteration of Seoul Mediacity Biennale since I was an undergraduate student. I first visited Seoul Mediacity Biennale exactly 10 years ago, during SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2014 Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers curated by Park Chan-kyong. This was two years after I had ‘laundered’ my academic status from the Department of Oriental Painting to the Department of Aesthetics, and I never again had the experience of viewing the same exhibition multiple times with such intensity, to the point of devouring even the artwork captions. A few years later, when my friends and acquaintances began participating in Seoul Mediacity Biennale as artists, it felt more accessible and even familiar(?), but the Biennale nevertheless seemed like a prestigious gateway to the art world – young, fresh and even honorable. Although it seems to have settled into a seemingly unremarkable biennial routine in recent years, it felt much different then. I bring up such memories from ‘back in my day’ in order to explain why I really didn’t want to introduce myself as a subject in this commissioned piece. There was so much that could have been said without including ‘me’!

However, I ultimately couldn’t avoid this personal perspective because I am, both then and now, a ‘rural-born’ ‘queer’ ‘otaku’ who inevitably feels ‘division and contradiction’ in relation to ‘Seoul,’ ‘Media,’ ‘City’ and ‘Biennale.’ Art barely granted me entry on the condition that I completely deodorize the scents of my other worlds – lesbian establishments and doujinshi sales conventions. At least, that’s what I thought. Due to my inferiority complex about being from a ‘subcultural background,’ I even hid the fact that I graduated from an animation high school and had long aspired to be a comic artist, especially in front of ‘pure-blooded’ art/aesthetics majors. Even after officially ‘debuting’ as an art critic through the SeMA-Hana Criticism Award hosted by Seoul Museum of Art in 2021, I still feel a certain tension toward art as ‘high’ culture. I know there are many others who feel the same way today, when art majors of various backgrounds are being (over)produced by universities as instruments of class reproduction, which has been ongoing since the 1990s.

While we might simply downgrade contemporary art to just another ‘genre’ of visual culture, hierarchies between genres still exist. If, as literary critic Young-chan Kim suggests, we consider the 1990s as a “period of compromise formation”4 between a past symbolized by the ‘democratization movement’ in the 1980s and the as-yet unrealized future of ‘postmodernism’ in the 2000s, while also integrating art critic Hye-jin Moon’s premise of a period of “translation”5 and “self-transformation”6 of Western theory, we inevitably arrive at a provisional hypothesis that the explosively generated infrastructure of the Korean art world also produced ‘inter-genre hierarchies’ that have been perpetuated to this day through certain compromises and translations. Such hierarchies are likely the result of loosely accumulated moment-by-moment decisions about what ought to be included and excluded in definitions of art, as mentioned earlier regarding Seoul Mediacity Biennale. Of course, this process itself can be explained through the mechanical will that endows ‘institutions’ with agency beyond individual determinations, somehow rendering it natural. Nevertheless, it is important to note that inter-genre hierarchies are ‘constructed’ and ‘represented’ through actor networks. This is not as ‘natural’ as it appears – just as it is ‘unnatural’ to feel excessive shame about one’s subcultural ‘roots’ while being caught between art and subculture. While it may be beyond the scope of this essay, any such personal complex of ‘division and contradiction’ in the context of art needs to be critically historicized from the perspective of reproducing inter-genre hierarchies as the art world’s principle of self-preservation.

My proposal to view not only the history of Seoul Mediacity Biennale but the entire history of art as a history of exploitation(!) and separation from subculture – as well as a history of ‘division and contradiction’ felt by subjects caught between subculture and ‘high’ culture – might sound like a plausible challenge to some, while others might perceive it as inappropriate friendly fire from someone who has lost sight of their own position. One clear fact is that the catalyst for my journey to this point was the video of a cosplay show from Digital Culture Festival for Adolescents, a corollary event of the 1st Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 in 2000.7 When watching this video, which happened to be the first one I selected from the vast Seoul Mediacity Biennale archive, I was captivated from start to finish. Strangely, it felt like finally discovering a lost recording – or more precisely, a recording that couldn’t be lost because it never existed – of cosplay competitions commonly seen at Busan Comic World (‘BUCO’ for short) in the 2000s, in an entirely unexpected(?) place. Often, this is how underground existence emerges by borrowing the forms of the mainstream.

Co-hosted by the newspaper Chosun Ilbo and the City of Seoul, Digital Culture Festival for Adolescents was designed not only as a platform for cosplay shows but also as a means of fostering and encouraging ‘amateur cultural warriors’ in various fields such as gaming, video and music, which were emerging as ‘wholesome’ youth cultures at the time.8 Therefore, this ambiguously positioned auxiliary event, which neither represents nor explains the history of Seoul Mediacity Biennale, nonetheless proves that there was a period when both the Biennale and art museums were uncertain about how to define notions of ‘public,’ art, media and culture. In other words, 2000 was a peculiar year in which cosplay shows and Nam June Paik coexisted under the name of ‘Biennale.’

At this point, we need to revisit the 1990s as an ‘ongoing’ period because after the 1998 import liberalization of Japanese culture, Comic World (operated by a Japanese company) first landed in Seoul in 1999 as a separate entity from existing domestic amateur manga doujinshi events like ACA (Amateur Comics Association). While the history of domestic ‘otaku’ or ‘mania’ can be traced much further back, the ‘democratization’ of subcultural identities like ‘doujin woman (yaoi woman),’ ‘cos-er (cosplayer)’ and ‘odeokhu (otaku)’ should be anchored to the late 1990s. I too was an amateur creator, a ‘doujin woman,’ who frequented Busan’s BEXCO Convention Center located between BEXCO Station and Centum City Station on Line 2 of the city’s subway, ever since the early 2000s when Busan Comic World had only been held a handful of times. Although Busan Museum of Art was always visible across the street from BEXCO, I never went inside. While geographically sharing the same space, they existed as two completely divided cultural worlds.

This landscape of divided worlds repeatedly appears in the video of Digital Culture Festival for Adolescents. The event’s baby-faced host speaks in a fluent Seoul dialect while wearing thick clothing that appears to be made of mouton material. It was held in September, which unexpectedly makes us recall the climate crisis. Watching the host make small talk (or deliver a soliloquy?) while waiting for cosplayers who were probably running late and checking their costumes, it’s reasonable to assume that this wasn’t the host’s first such event. Finally, a group of cosplayers called under the name ‘Wind’s Lunch’ appears, dressed in costumes from the manga Rurouni Kenshin, and reenacts its climactic duel scene. Cosplayers pair up and strike poses that correspond to their characters, with remixed music completely unrelated to Rurouni Kenshin playing – I suspect this was either because the original soundtrack was hard to obtain or because ‘Japanese music’ couldn’t yet be played in public spaces. Other groups of cosplayers are then called to the stage in succession and audience members dressed as cosplayers also appear on screen. In the background, Seoul High School is visible near Gyeonghuigung Palace, which formerly served as the office of Seoul Museum of Art before the Seosomun main building opened in 2002 as the museum’s headquarters. Regardless of Biennale’s proximity, groups of ‘youth’ cosplayers seem purely happy in the video. They would probably feel the same way if the event had taken place anywhere else. I decided to highlight this aspect of Seoul Mediacity Biennale’s archives as ‘merely’ subculture in order to preserve their joy that can neither be exchanged nor sublimated. This is why such a long ritual was necessary.

-

Dong-yeon Lee, ed. Does Subculture Resist? (Cultural Science Press, 1998). ↩

-

“Q: How was Art Vision City Vision received by the public? A: At the time, Roh Hyung Suk, who is still working at The Hankyoreh today, had just started working as an art journalist, and he showed a particular interest in this project. One time, we went out to the Gwanghwamun intersection together to see the billboards on the buildings of the Dong-A Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo, and Roh was asking questions to random people on the street. However, most people didn’t really notice the videos-or, at least, they didn’t realize that the videos were different from the regular advertisements that appeared on the billboards. They just thought of them as new advertisements and didn’t see them as ‘artwork’s.’” Jin Kwon, “Conversation with Lee Sop, Media Art = Publicness,” in Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996-2022 Report (Seoul Museum of Art, 2002), 51. ↩

-

Ji-eon Shim, “Hong-hee Kim & Nan-ji Yoon’s Herstory,” Monthly Art Magazine, December 2024, 51. ↩

-

Young-chan Kim, “There is No ’90s’ - An Essay, A Code for Reading the ‘1990s’,” in Symptoms of the 1990s, ed.Keimyung University Institute of Korean Studies (Keimyung University Press, 2017), 15. ↩

-

Hye-jin Moon, Korean Art in the 1990s and Postmodernism (Hyunsil Publishing, 2015), 14. ↩

-

ibid, 301. ↩

-

Seoul Mediacity Biennale YouTube Channel. “SMB01 Digital Culture Festival for Adolescents.” Posted July 4, 2024, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vc5eK90Bhvg&t=255s ↩

-

“[Notice] 2000 Digital Culture Festival for Adolescents.” Chosun Ilbo, last updated October 13, 2000, https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2000/10/13/2000101370135.html ↩