The Public Nature of Seoul Mediacity Biennale

In this research, Haeyun Park engages in a meta-critical reading of the Seoul Mediacity Biennale’s history. Park revisited The 1st SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 (1996) and media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 (2000) to carefully re-examine how past experiments conceived the public nature inherent in video art with images beyond mediating another way of seeing and thinking beyond the institutional limitations, while emphasizing the importance of historical continuum of Seoul Mediacity Biennale.

Haeyun Park is an art historian and critic specializing in contemporary art. She is a professor at Kyung Hee University, where her research focuses on early video art, performance art and institutional critique of the 1970s. Her writings have been published by Artforum, New Museum New York, Keio University Art Center and Gallery Hyundai, among others. She received her B.A. in History from Yale University, M.A. in East Asian Studies and Art History from Columbia University, and Ph.D. in Art History from The City University of New York.

Research Title The Public Nature of Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Category Essay

Edition The 13th Seoul Mediacity pre-Biennale

Author Haeyun Park

Korean-English Translator Barun

English Copyediting Andy St. Louis

For all of us, beginnings are inherently significant.

In one’s personal life, first attempts can be clumsy, marked by a mix of excitement and fear about venturing into something new. Yet it is the steady accumulation of firsts that shapes an individual’s history and ultimately constitutes the very essence of one’s life.

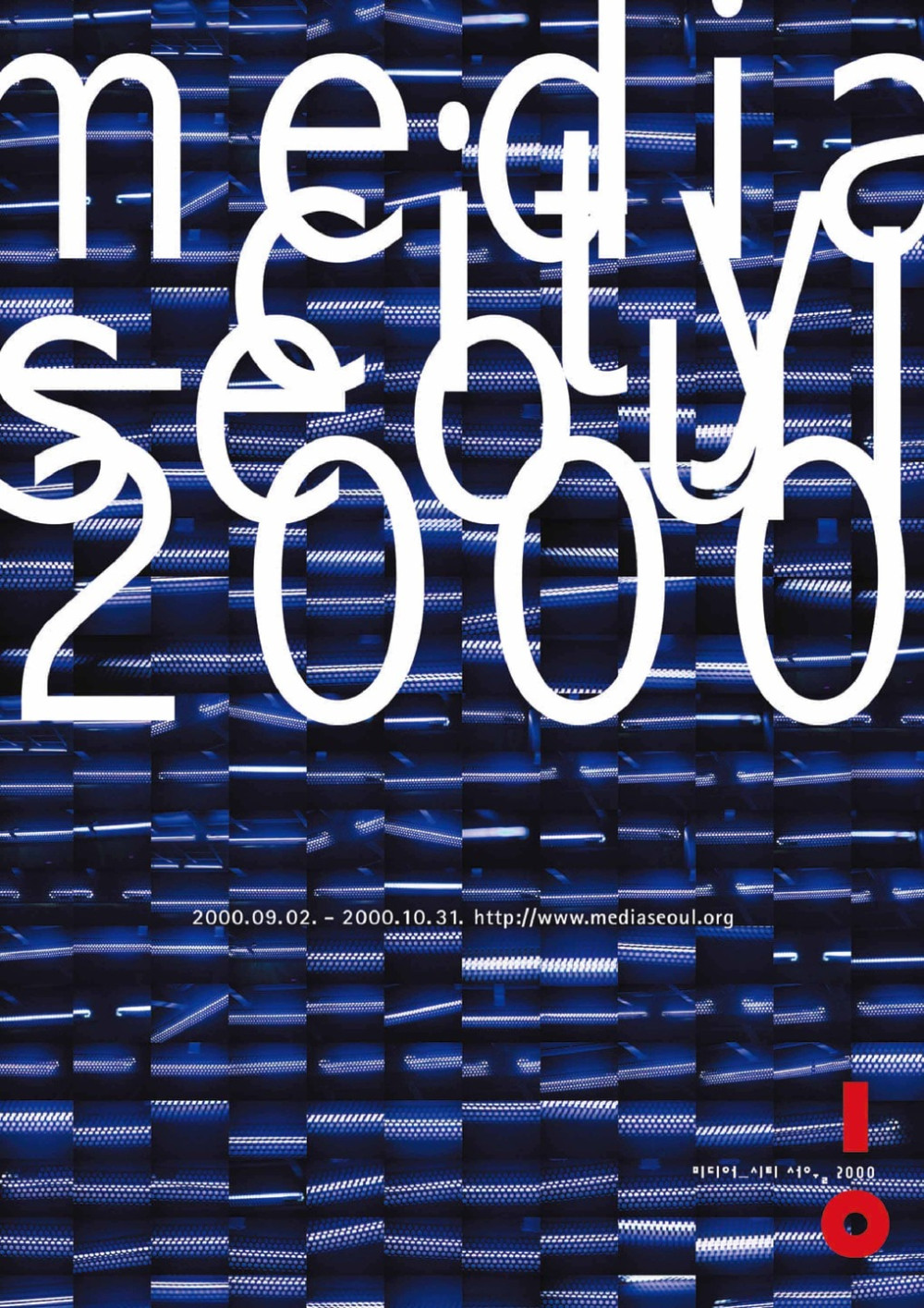

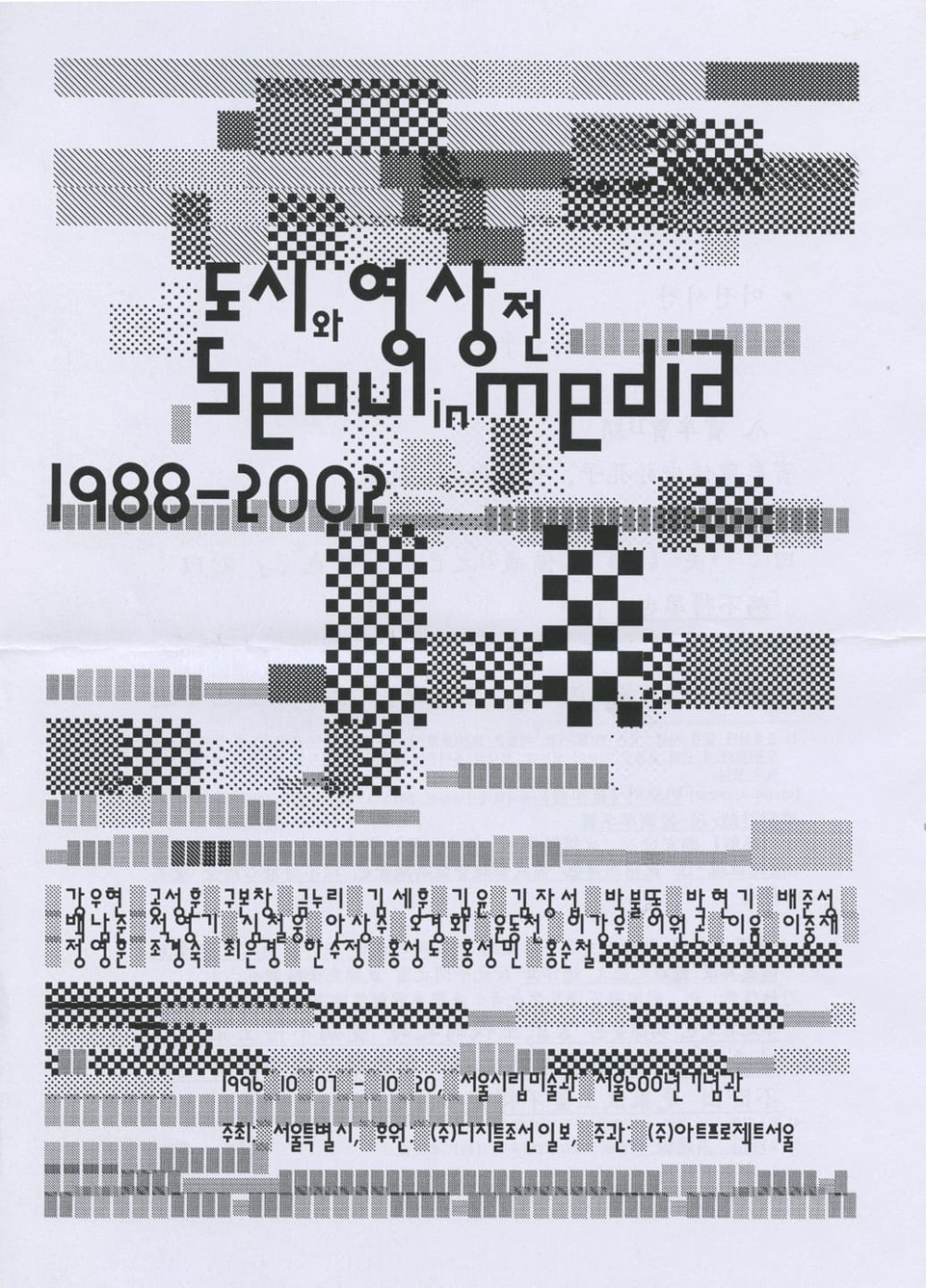

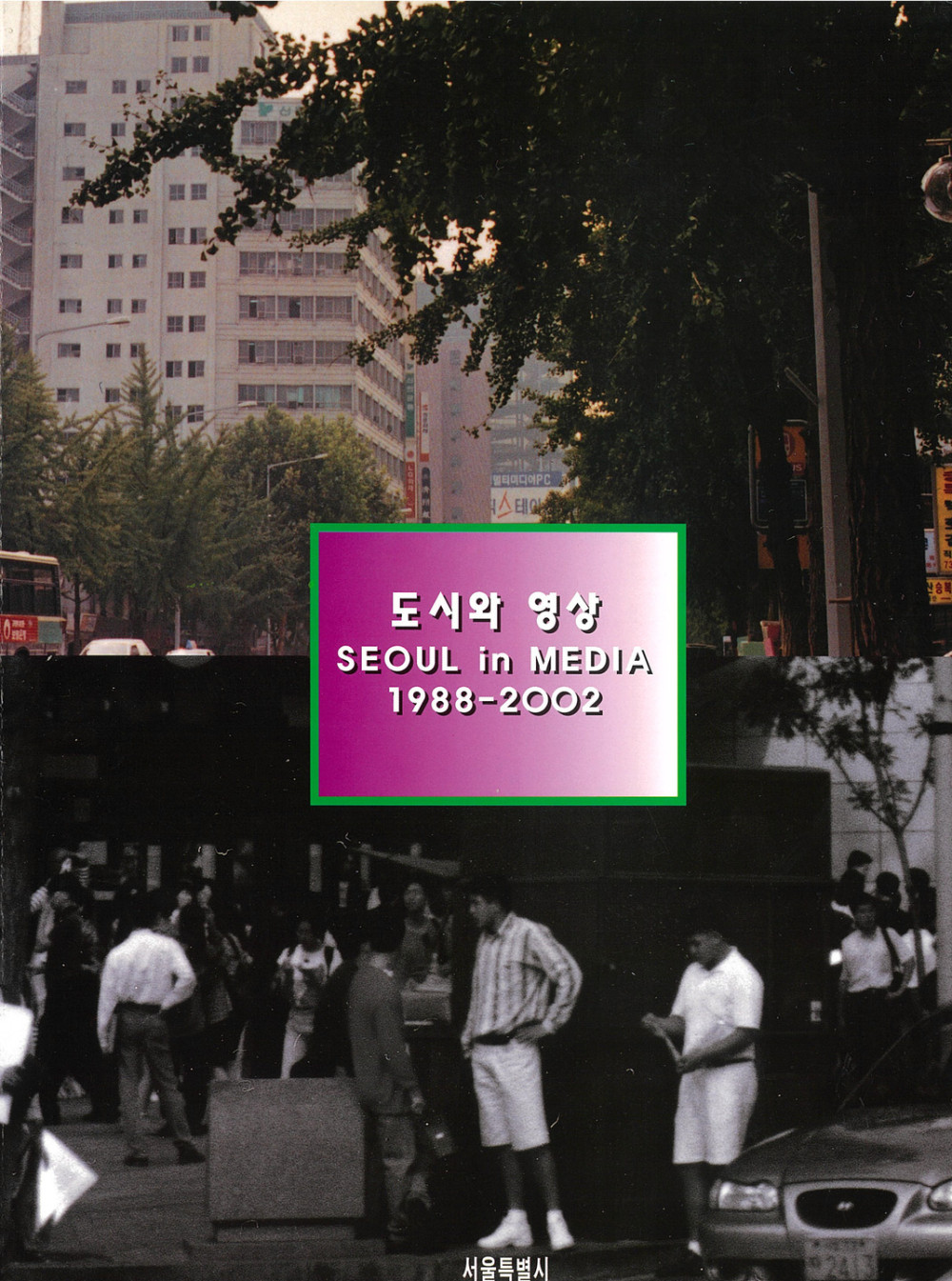

The significance of beginnings extends beyond individual lives to include institutions of public character, particularly state-operated art museums. As the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (SMB) approaches, reflections about its origins assume a heightened resonance. This essay examines two of SMB’s foundational editions: the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 held in 1996 and media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 held in 2000, with particular attention on their shared focus on the “public nature of video art.”

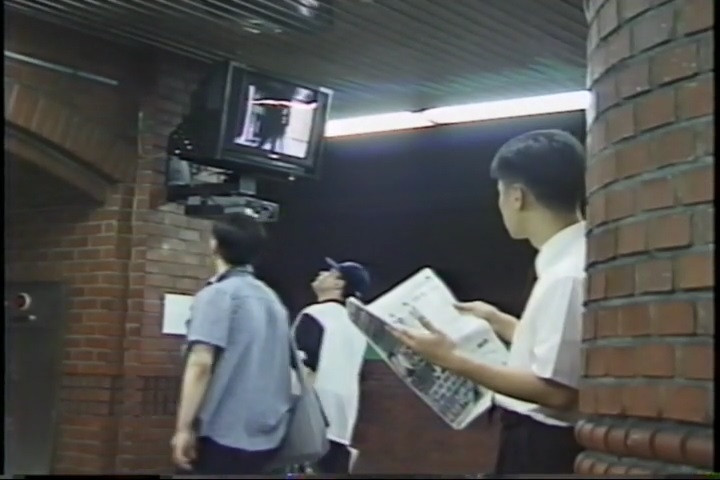

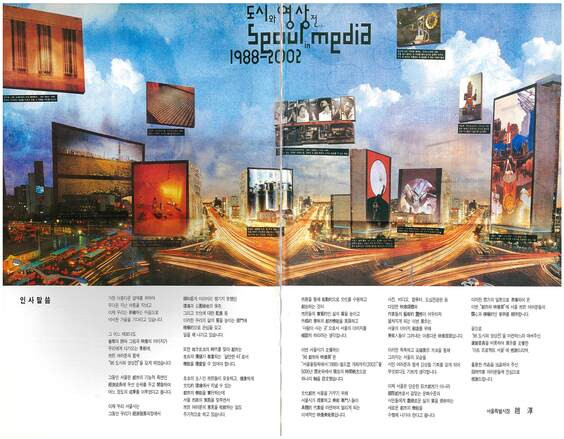

The journey of Seoul Mediacity Biennale started in 1996 with the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002. Its exhibition catalog opens with a striking visual: against the backdrop of Seoul’s glittering nightscape, streams of car lights rush past while video artworks from participating artists are projected onto electronic displays mounted on towering buildings, creating an ethereal effect of images floating across the sky. Reality on the ground mirrored this vision, with edited versions of the artists’ video works displayed across 14 urban electronic billboards in Seoul and four other cities, catching the eyes of busy urbanites going about their daily lives.1

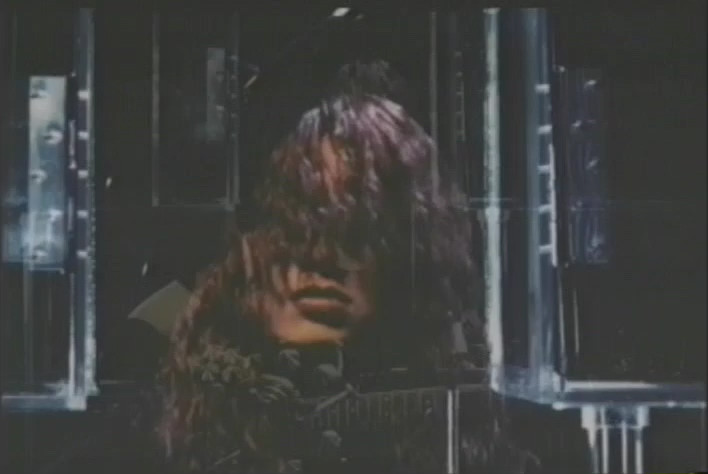

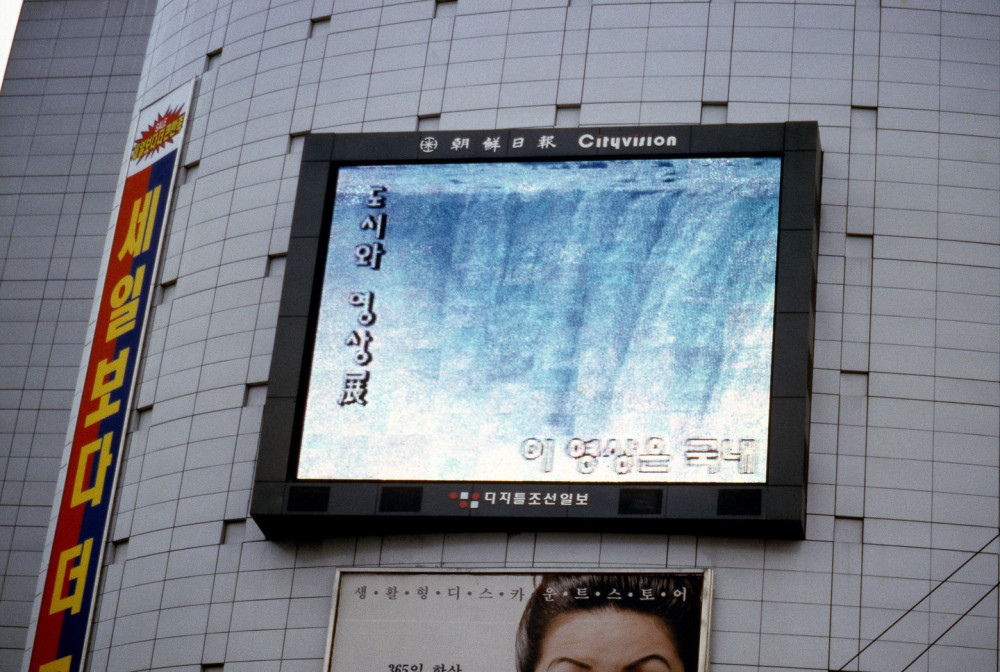

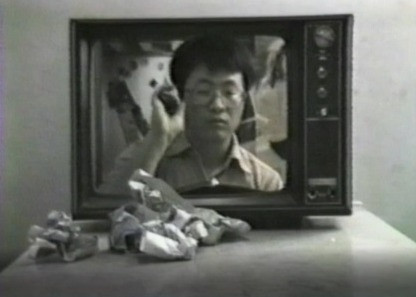

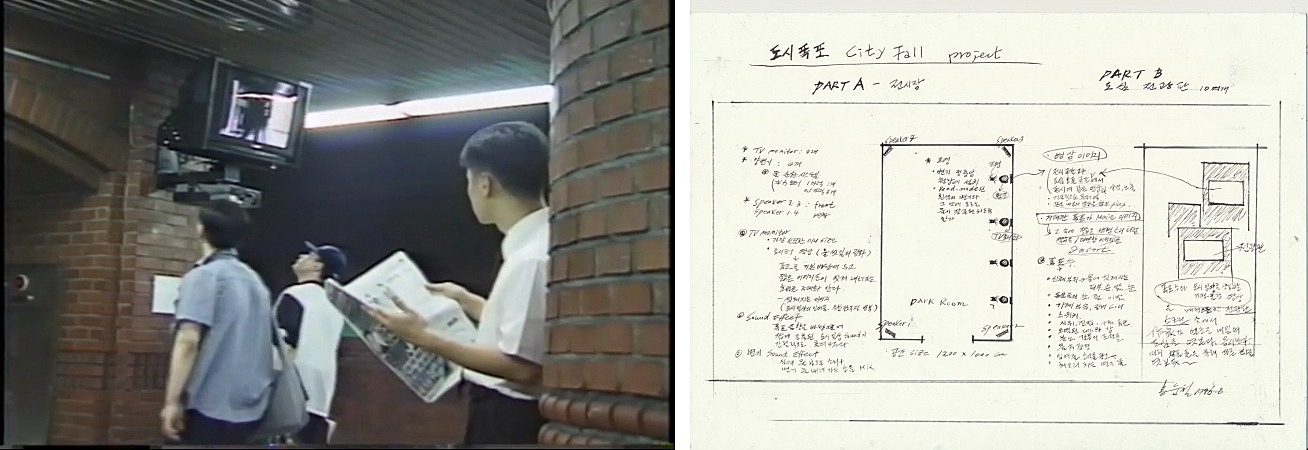

After a sequence of commercial advertisements for LG Fire Insurance, Ace Bed, Kodak, Lotte Department Store and McDonald’s, the electronic displays mounted on Seoul’s various urban landmarks - including the Koreana Hotel in Gwanghwamun, Grand Department Store in Sinchon and Jonggak Seowon in Jongno – screened a series of video works. The sequence opened with Hong Soon-chyul’s City Waterfall (1996), in which a bespectacled man’s face appeared and disappeared from different angles amidst rushing waterfalls and swirling toilet water. This was followed by a rapid cross-edit of Rhee Yoom’s Capsule People (1996) and Yi Won-kon’s Silkroad Memorial-under the linden (1986/1989), before ending with Park Hyunki’s THE BLUE DINING TABLE (unknown date), which shows the artist slowly rolling a stone between his feet.

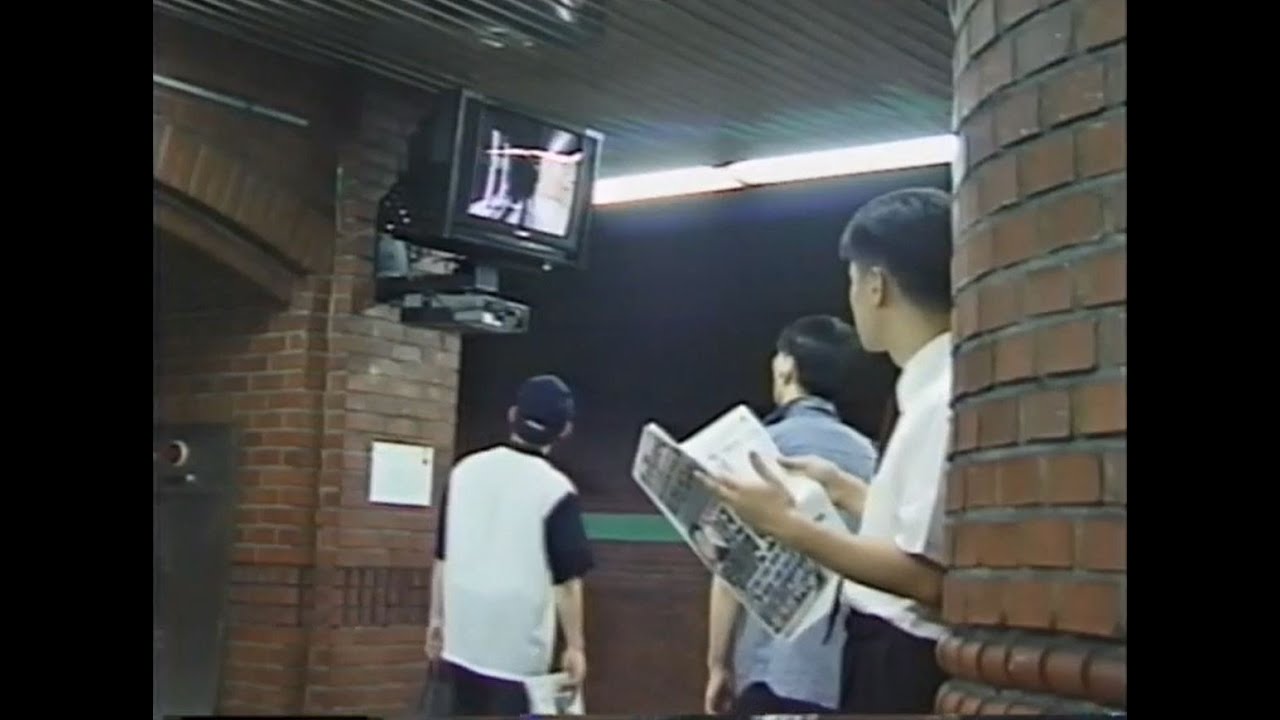

This public screening initiative, titled ART VISION CITY VISION, also extended to bank information TVs, a common feature in Korean banks that advertised financial products and reminded waiting customers of proper banking etiquette.2 Artists’ video works were integrated into this existing content stream, playing once every hour. What made the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 exhibition particularly groundbreaking was its departure from the traditional gallery context and its corresponding ability to infiltrate spaces frequented by ordinary citizens.

Curator Lee Sop, who organized the exhibition, explained that the project was conceived to highlight the public nature inherent in video art, and that publicness meant finding “the point where artistic activity doesn’t become divorced from everyday life.” Lee hoped that artists would transcend the perception of video as merely another genre of art and instead see it as an opportunity to bridge the gap between art and daily life by showcasing their works in public spaces where ordinary citizens go about their everyday routines.3

In his catalog essay “Curating the SEOUL in MEDIA Exhibition,” co-curator Kim Jinha discusses how video penetrated people’s daily lives through mass media during the transition from industrial to information society. He notes that the moving images which were broadcast on TV injected the desire for entertainment and commercial consumerism into the public consciousness. While highlighting how mass media has come to regulate the way people communicate with each other and the way they think, he discusses the significance of video art as a counterpoint to this dominant media landscape.4

“Video art is productive in its capacity for de-institutionalization. Though video art language relies on technology and science-based media, it demands that we see and think differently. … In video art, an event or an object retains a specific character through the thoughts or sensibilities of the artist. … Furthermore, artistic language … captures and reflects individual consciousness and individuality, leading to deeper contemplation of the characteristics of life in a specific time and the complexities within urban spaces. It secures its social value through its orientation toward expanded self-expression, a spirit of experimentation and a ‘gaze’ that views society horizontally.” 5

What is particularly striking in Kim’s description is his characterization of video art’s function as a vehicle for de-institutionalization. It is fascinating to think about the positioning of broadcast media’s spectacular, consumption-oriented culture in the context of institutional video culture, while emphasizing video art’s individuality in opposition to this mainstream current. Furthermore, Kim explains the objectives of SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 in response to the video media era as “reflecting Seoul’s life and cultural identity from video artists’ perspectives and seeking everyday qualities and visuality through entirely personal and delicate artistic observation.”6

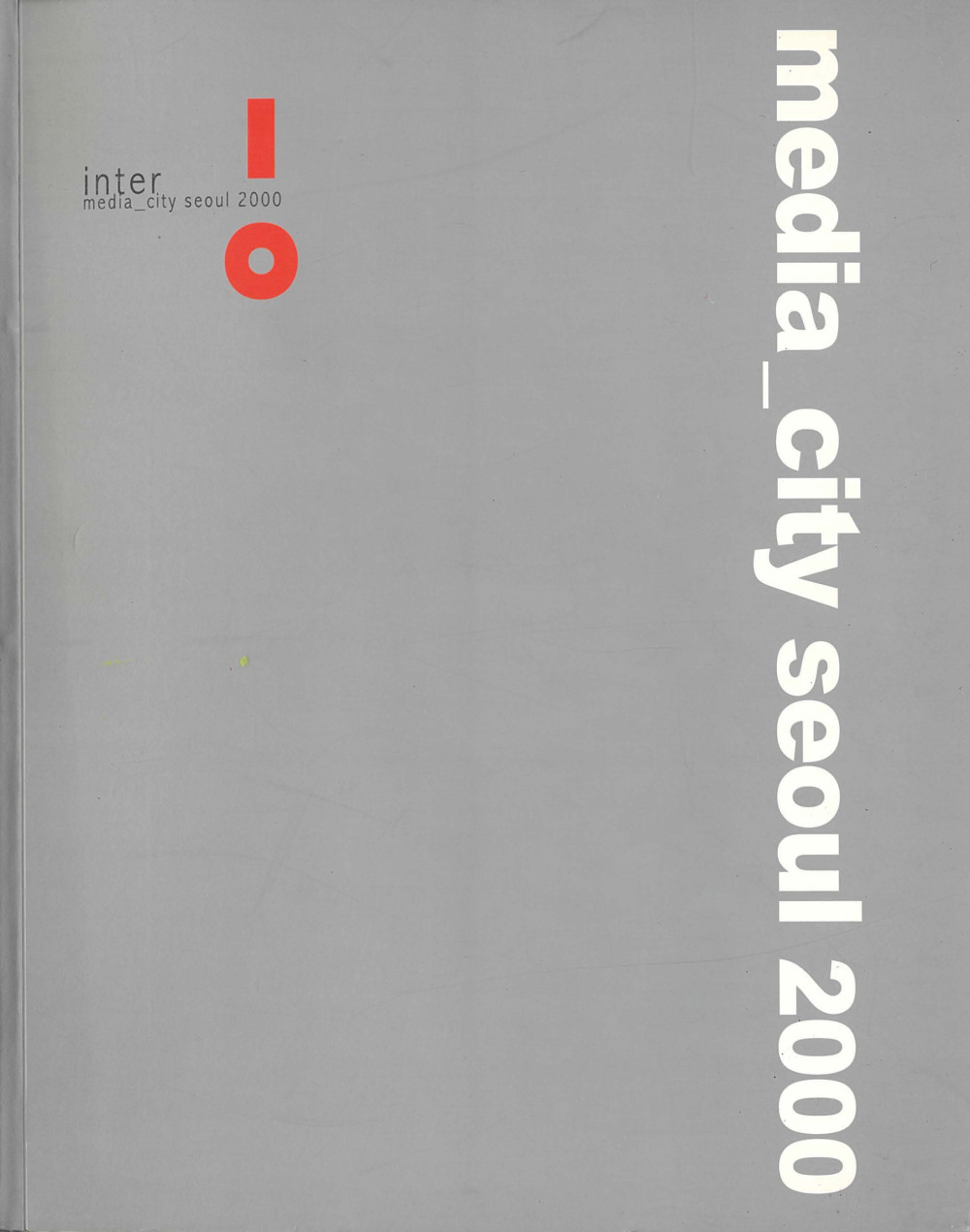

The “public” nature of video was a theme that distinguished the initial direction of the Seoul Mediacity Biennale, which evolved into two key projects – “City Vision/Clip City” and “Subway Project - Public Furniture” – out of the five major projects comprising media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 that was held four years later. media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 encompassed a total of three exhibitions, with the main exhibition, “Escape”, held at the Seoul Museum of History (formerly Seoul Municipal Museum).7 Co-curated by Barbara London and Jeremy Miller, it created significant buzz as the first exhibition to introduce major global media art pioneers that had not previously been exhibited in Korea – including Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson and Joan Jonas – alongside emerging international video artists such as Matthew Barney, Tony Oursler, Bill Viola and Douglas Gordon.

“City Vision/Clip City”, which aimed to transform commercial billboards into spaces for public video art, was another significant component of media_city seoul 2000. Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist invited 25 artists to create short video pieces ranging from 20 to 50 seconds (similar in length to commercial advertisements), which were transferred to Betamax tapes and displayed across 42 electronic billboards throughout Seoul.8 Although “City Vision/Clip City” was impressive in its inclusion of works by renowned artists like Pipilotti Rist, Chantal Akerman, Christian Boltanski and Alexander Kluge, one might question whether merely displaying these videos on billboards truly transformed these outdoor spaces from commercial to public use.

In my view, “Subway Project - Public Furniture” curated by Ryu Byoung Hak aligned more closely with the stated goal of media_city seoul 2000: to “highlight art’s public nature and the city’s role as media.” According to Ryu, this project was conceived to dissolve the boundary between the everyday world and art world. It cleverly defined Seoul’s subway stations as spaces of “entry and exit”: spaces that exhibit “a bidirectional flow of two streams of movement,” drawing an intriguing parallel between the method of “input and output” intrinsic to video art and computer technology.9

Ryu envisioned Line 2 of the Seoul Subway, which follows a circular path around the city, not as a closed circle but as an open ellipse capable of expansion to other regions. Among the 43 stations on Line 2, Ryu selected 12 transfer stations as exhibition venues, along with Gwanghwamun Station on Line 5, which was also included due to its proximity to the main exhibition spaces of media_city seoul 2000: namely, Seoul Museum of History and Seoul 600-Year Memorial Hall (formerly SeMA Gyeonghuigung).10

The “Subway Project - Public Furniture” championed the concept of public furniture as an attempt to merge functionality with aesthetics and exhibited site-specific works that each participating artist created after visiting their designated subway station location.11 Ryu viewed these works as “media connecting underground regions along the geographical route of the subway line,” bringing new meaning to the underground spaces of transit used by citizens every day.12 What stands out about this project was its flexible approach to the notion of a medium – in addition to video works, it also included various formats such as mother-of-pearl murals and sculptures which doubled as chairs that passengers could sit on.

Lee Soo Kyung’s artwork Subway Line 2 (2000) adopts the unique perspective of a subway train operator during moments of transition from above ground to below ground, which passengers typically experience as a period of temporary darkness. Lee filmed both ground-level and underground scenery along the entire route of Line 2 from the viewpoint of a train conductor, then created a montage by combining this footage with computer-animated cross-sections of continuously running trains at the bottom of the screen. Lee’s work was installed at five subway stations: Dongdaemun Stadium, City Hall, Sindorim, Seoul National University of Education and Jamsil. According to the artist’s intention, Subway Line 2 aligned perfectly with the theme of “between 0 and 1” adopted by media_city seoul 2000 in the process of “revealing what is shown and hidden … from the train’s perspective.”13

Jiki Park’s artwork Silk Road (2000) transformed a 150-meter transfer corridor connecting the Line 2 and Line 8 platforms at Jamsil Station. The artist installed more than ten 29-inch TV monitors along the ceiling’s horizontal supports and covered everything but their screens with white artificial fur. Each monitor displayed natural landscapes that were synced to the musical score of Byungki Hwang’s Silk Road.14 This work successfully reimagined a tedious passageway into a stage for commuters to experience new audiovisual stimulation.

Reading through the foreword of the media_city seoul 2000 exhibition catalogue, one repeatedly encounters the phrase “digital revolution” – driven by the emergence and expansion of the internet – as a central theme.15 The exhibitipn’s subtheme of “Between 0 and 1,” which sounds somewhat outdated from a present-day perspective, reveals the exhibition’s techno-utopian vision of bidirectional digital technology and its capacity to effect revolutionary changes in our lives. Compared to broadcast media, which the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 exhibition criticized as a producer of consumption-oriented culture, the internet was considered a means of lending a voice to the anonymous masses, as well as facilitating access to public discourse that must have felt revolutionary at the time, indeed.

However, a quarter century later, our current reality presents a sobering perspective on digital media, which has become dominated by social networks. What many people in the late 1990s and early 2000s envisioned as a revival of an ancient Greek agora of direct democracy has become a virtual space inundated with fake news, propaganda and hate speech. YouTube and Google algorithms repeatedly expose users to digital contents that cater to their preexisting preferences, thereby inadvertently promoting biased thinking. Moreover, these platforms are often misused as tools for endlessly flaunting and promoting glamorous, consumption-oriented lifestyles.

By the same token, however, the internet also has positive functions. Just ten days before writing this essay, Korean soldiers entered the National Assembly building following the declaration of martial law on December 3, 2025. However, they were unable to shut down the parliamentary proceedings inside or control the situation as quickly as they wished. This was largely because citizens had rushed to the National Assembly’s main gate and shared real-time footage of the soldiers via their phones, spreading the news across the internet and drawing journalists and crowds to the scene. This duality of the internet reminds us that technology alone cannot advance society – what matters is who uses it, how it is used and for what purpose. It also underscores the importance of art as an avenue for reading and contemplating such phenomena.

At this juncture, I hope Seoul Mediacity Biennale will continue to develop its public character that was central to both the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002 exhibition and media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1. Today’s popular blockbuster exhibitions typically feature dazzling videos on enormous media walls that tower over viewers or immersive installations like those by TeamLab. Overwhelmed by the constant audiovisual stimulation, visitors are often too busy taking selfies in front of the spectacular backdrops to devote the mental and physical space necessary to achieve a critical distance from artworks and to contemplate their meanings.

Our late-capitalist society enthusiastically embraces new technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality and artificial intelligence, often making a fuss whenever these technologies are applied to contemporary art as if it constitutes a revolutionary audiovisual or multi-sensory change. Meanwhile, more than three decades after the emergence of the World Wide Web in 1990, people now recognize the folly of blind techno-centrism and technological optimism. The future of media art must transcend merely applying new technologies to art and instead probe the gaps in algorithm-driven personalization on digital platforms, leading audiences to critically reflect on our relentlessly spinning, consumption-oriented culture. It is with this hope for media art’s critical engagement with contemporary digital culture that I conclude this essay.

-

According to Lee Sop, curator of the first SEOUL in MEDIA 1988-2002, all videos displayed on electronic billboards were formatted to run slightly under 90 seconds. To accommodate this constraint, works from ten participating artists (still images and videos) were edited into a consolidated segment, with the compiled tape playing every two hours on the displays. “Conversation with Lee Sop, Media Art = Publicness,” Seoul Mediacity Biennale 1996-2022 Report (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, 2022), 46. ↩

-

Eight Korean banks that participated in “ART VISION CITY VISION”: NH, KEB, Commercial Bank, Exchange Bank, Cho Heung, First Bank, Hana and Hanil. ↩

-

Ibid., 45-46. ↩

-

Kim Jinha, “Curating the SEOUL in MEDIA Exhibition,” The First Seoul in Media 1988-2002 Catalogue (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, 1996) ↩

-

Ibid., 6-7. ↩

-

Ibid., 6-7. ↩

-

Song Misuk, “Foreword,” The 1st Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 Catalogue (Seoul: media_City seoul Organizing Committee, 2000), 13. ↩

-

Ibid., 15. ↩

-

Ryu Byoung Hak, “Subway Project - Public Furniture,” The 1st Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 Catalogue, 259, 261. ↩

-

Ibid., 261. ↩

-

Ibid., 264. ↩

-

Ibid., 264. ↩

-

Yeesookyung, “The Subway Number 2 Line,” The 1st Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 Catalogue, 268-269. ↩

-

Kyong Lee, Jiki Park’s “Silk Road,” The 1st Seoul International Media Art Biennale media_city seoul 2000 city: between 0 and 1 Catalogue, 271 ↩

-

Song Misuk, “Foreword,” 9. ↩